Nonviolent Communication in Social Work

Francesca Lamedica

Social worker, indipendent researcher

CORRESPONDENCE:

Francesca Lamedica

e-mail: francesca.lamedica@gmail.com

Abstract

This paper intends to present the possible fields of application of Nonviolent (or Empathic/Collaborative/Compassionate) Communication (NVC) to Social Work, and its benefits for the wellbeing of service users, practitioners, the professional environment, and organisations. This presentation will be supported by an overview of relevant literature and research. A particular focus will be on the helping relationship, highlighting the essential role that Nonviolent Communication can play especially in the interview, but also throughout the whole helping process. NVC values — as empathic listening, mutuality and reciprocity, authenticity, empowerment, consideration of the other’s feelings and needs — applied to Social Work fundamentally coincide with the approach promoted by Relational Social Work. Moreover, NVC provides social workers also with valuable tools enabling them to build the necessary self-awareness and inner availability to engage in a truly helping relationship. This self-awareness about the own needs is also crucial to engage in healthy and constructive professional relations with colleagues and the organization, and to prevent burnout.

Keywords

Nonviolent communication, helping relationship, child protection, aggressivity & shame, burnout prevention, professional relations.

Introduction

Many of the founding principles of Nonviolent Communication — such as honesty, authenticity, empathic listening, mutuality and reciprocity, consideration, respect and inclusion for the other person’s feelings and needs, promotion of cooperation through the exercise of power with the other person instead of over the other person — fundamentally coincide with the generally known principles that should guide social workers. In particular, Relational Social Work promotes an approach based on reciprocity, acceptance of the other person and empowerment (Folgheraiter, 2011; Rogers, 1977; Mucchielli, 1998), participation (Calcaterra & Raineri, 2021, 2022; Warren 2007), and anti-oppressive and anti-discriminatory Social Work (Dominelli, 2002; Thompson, 2016; Tedam, 2021). The helping relationship, rooted in reciprocity and trust, should encourage active participation of service users in the decision-making process, mitigating the effects of power and oppression within social services.

A special focus will be devoted to the area of child protection as an area in which communication between professionals and service users tends to take on a unilateral, if not directive, nature, based on the underlying judicial measures limiting parental responsibility. The needs of the parents are generally considered to be in conflict with the needs of their children, whose protection is entrusted to judicial bodies and to social services. However, NVC reminds us that behind every behaviour there is an unmet need, which has the same value and dignity of any other (person’s) need. Issues arise at the level of the strategies to meet these needs, that could be destructive and put others at risk or in danger. In that sense, the mission of Social Work in this field could move from a focus on children’s needs only to an inclusion of parents’ needs, giving them the opportunity to express them and to participate in the process. Their involvement by practitioners is essential since it is difficult to imagine how one can protect a child without also taking care of his or her family members (Calcaterra & Raineri, 2022). This approach is opposed to paternalistic attitudes that are often aimed at generating feelings of guilt and shame and ultimately compliance. NVC provides valuable tools to shift from an exercise of power over the service users, to a power with them. The aim of this process is to find, together with the families, strategies that can serve all the needs at stake.

Child protection is also one of the areas in which more frequently families turn to aggressive behaviours towards social workers, in reaction to unilateral measures. In this sense, NVC can not only help to prevent aggressiveness through promotion of reciprocity, participation and consideration of parents’ anger and needs, but also to respond to these behaviours reverting, when necessary, to a protective use of force, rather than a punitive one.

Finally, NVC can also provide support in burnout prevention, to improve professional relations and to respond to possible forms of oppression generated by organisations of social services, both towards practitioners and service users.

What is meant by Nonviolent Communication?

Nonviolent Communication (NVC, also known as Empathic, Collaborative or Compassionate Communication) is an approach to communication developed by Marshall Rosenberg (1934-2015), an American psychologist and former student and assistant of Carl Rogers, whose personcentered model (1961, 1969, 1977) is one of the pillars of Social Work knowledge and practice.

NVC is a «combination of thinking and language, as well as a means of using power designed to serve [the] intention to create the quality of connection with other people and oneself that allows […] [a]ll actions to be taken for the sole purpose of willingly contributing to the wellbeing of others and ourselves» (Rosenberg, 2005a, p. 16). This well-being implies the fulfilment of the needs of all parties involved, which, in the case of Social Work, are social workers themselves (also as representatives of the State), service users, their families and communities, and other professionals and services involved.

NVC indicates a specific communication approach and practice based on an empathic connection with oneself and others, whereas with «violent» communication is meant any sort of communication (verbal and non-verbal, speaking and listening) involving, for example, judging, blaming, demanding, speaking without listening, or stating who or what is good/bad or right/wrong. Rosenberg highlights that any words that imply the wrongness of others are «tragic» and «suicidal» (i.e., counterproductive and ineffective) expressions of unmet needs (2005a, pp. 28, 29, 68, 122), as they won’t lead people contributing to meet those needs or to do what we would like them to do. They just provoke defensiveness and counteraggression.

NVC invites us to reformulate our thoughts and language based on four elements, the socalled NVC steps or components, which are observation, identification of feelings, identification of needs and formulating requests.

These steps can be followed inwardly, to listen empathically and connect to oneself, or in the relationship with others, to listen empathically and connect with their feelings and needs.

In the first case of internal connection, the process would be: «When I see/hear ... [OBSERVATION]. I feel [FEELINGS] because I need (wish/it is important to me) ... [NEEDS]. Would you be willing to ...? [REQUEST]».

In the second case regarding external connection, the communication with the other person would sound: «When you see/hear... are you feeling..., because you need...?», to finally listen empathically to any possible request.

More specifically, in both cases, the four steps are the following ones:

- The observation of the facts answers to the question «What happened? What was said or done? What did I/you see or hear?». Focusing as much as possible on the objective facts and their neutral description implies distinguishing them from the interpretation we give of them and from the thoughts we formulate about them in the form of evaluations, (pre)judgements and generalisations. This is functional to becoming aware and taking responsibility for one’s own thoughts and distinguishing them from the objective facts. For example, for a social worker to say or think of someone that he’s totally unreliable and disrespectful [judgement] because he always arrives late [generalisation] and shows no interest in cooperating with Social services [interpretation] is very different from: «He arrived late for the third time [observation] and I’m noticing I’m thinking that he’s unreliable and disrespectful [awareness and responsibility for one’s own thoughts]».

- The identification of one’s feelings answers to the question «How do I/you feel about what happened?». This step is often difficult because we are more used to connecting with our thoughts — in the form of judgements/assessments/analysis — rather than to our feelings. Observing objective facts and recognising the thoughts connected to them helps to bring out the feelings triggered (rather than caused) by that specific situation. As a matter of fact, «what others say and do may be the stimulus, but never the cause, of our feelings» (Rosenberg, 2015, p. 80), which means that the responsibility for one’s own feelings lies with the person experiencing them, as they are connected to one’s own needs. As outlined below under the third step, other people are not responsible for fulfilling one’s own needs, nor for the related unpleasant feelings. In this sense, taking the example above, the rephrased sentence could be followed by: «… and I feel worried [awareness and responsibility for one’s own feelings] that he might not be willing to cooperate with the Services because for me cooperating is very important [awareness and responsibility for one’s own need; see under step 3]».

Furthermore, it is important not to confuse feelings with socalled «false» feelings, like feeling disrespected or manipulated — two examples of feelings that both social workers and service users might often experience — as these are not really feelings but rather interpretations of the other person’s behaviour or intentions. The question to be asked is hence: «How do I/you feel when I/you feel disrespected?». The answer could be «resentful», «sad», «worried» or «confused», depending on the needs that are not satisfied in that moment.

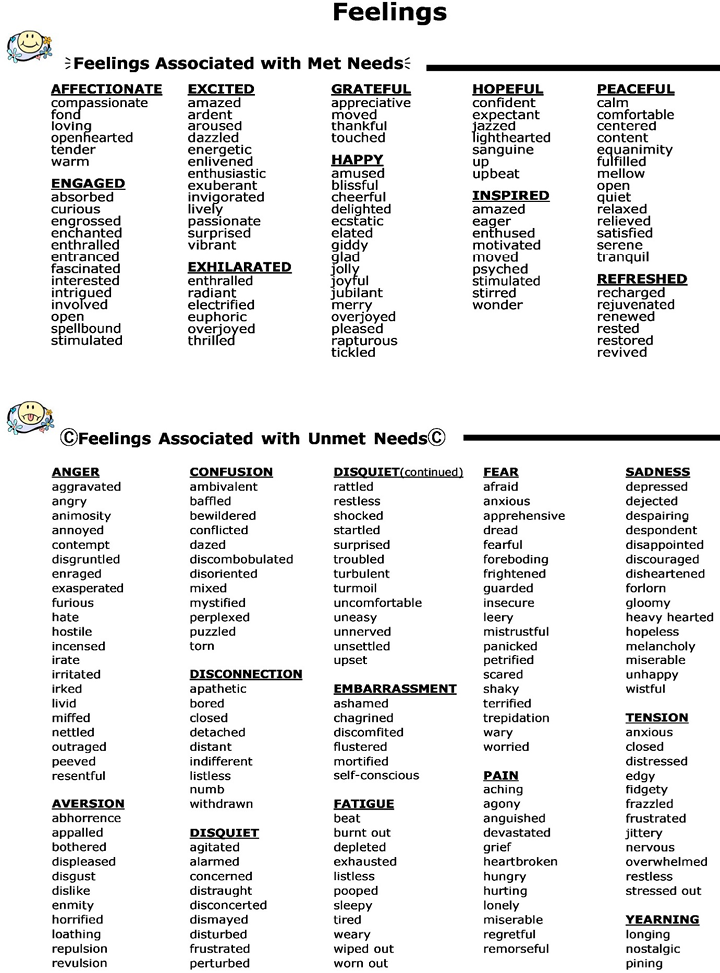

To facilitate the identification of feelings, they are listed in Annex 1.

- The identification of one’s needs answers to the question «What is the need that causes my/your feeling?». The identification of feelings helps to find the connected, underlying needs, as pleasant feelings are connected to needs being met and unpleasant feelings to unmet needs. Needs are the cornerstone of NVC as they serve life, i.e. they show what is alive in any person. The premise is that needs are all equally valuable, and that any action and choice we make is an attempt to meet our needs. In identifying needs, there is the possibility of going deeper and deeper, to delve into the most profound and essential needs. This is what may be called a «stratification» of needs, where the most superficial need is like the tip of an iceberg, and it often serves just as a strategy to satisfy the deeper needs. So, in the cited example of the person being late for the appointment, the social worker might ask him/herself: «When my need for cooperation is satisfied, what other need is satisfied?». This could be, for example, the need of value or contribution. The deeper one goes in the search for needs, the clearer it becomes that their satisfaction is disconnected from other people’s behaviours. «In order not to confuse needs and strategies, it is important to recall that needs contain no reference to anybody taking any particular action» (Rosenberg, ٢٠١٥, p. 210). This indicates the importance of distinguishing the two concepts. Needs are universal (meaning that everybody shares them) and their satisfaction is the sole responsibility of the person who has them, whereas strategies are concrete, specific and, if developed unilaterally, may conflict with other people’s strategies. Indeed, conflicts arise at the level of strategies, not of needs, and NVC aims precisely at bringing out and considering the needs of all concerned ones so that they can jointly develop strategies that meet everyone’s needs.

As for feelings, the responsibility for one’s needs belongs to the person who has them, and not to the person who we think should meet them, hence it follows that others are not responsible for either our needs or how we feel. NVC invites to move from the formula «I feel [...] because you (/he/she/they/ society/etc.) […]» to «I feel [...] because I (need) ...».

This awareness is what enables the person to get out of the position of powerless victim and to access empowerment, in a spirit of autonomy and selfdetermination (cardinal principles of the social work profession) in choosing how to act. This reminds of the words attributed to Viktor Frankl: «Between stimulus and response lies a space. In that space lie our freedom and power to choose a response. In our response lies our growth and our happiness».

Turning to the example above, the relationship between the social worker and the service-user would be very different if, instead of the former just observing the facts, without interpreting them, and become aware of his/her feelings and needs, he/she reacted to the client’s lateness by telling him: «You are totally unreliable because you always arrive late and show no interest in cooperating». Such a sort of communication would surely in turn provoke another reaction, most probably an aggressive or defensive one, as e.g. «It’s not my fault that my job is far away», or a formally complying one, out of fear of the consequences (especially in the field of child protection). This will surely not lead to an increased cooperation. On the opposite, if the same social worker shows genuine interest, without preconception, for the client’s needs — what might he need to be able to come on time to the appointment? What other needs is he trying to satisfy that makes him late? — a dialogue can open and from there a helping relationship. «Understanding human needs is half the job of meeting them» (Rosenberg, 2005a, p. 37).

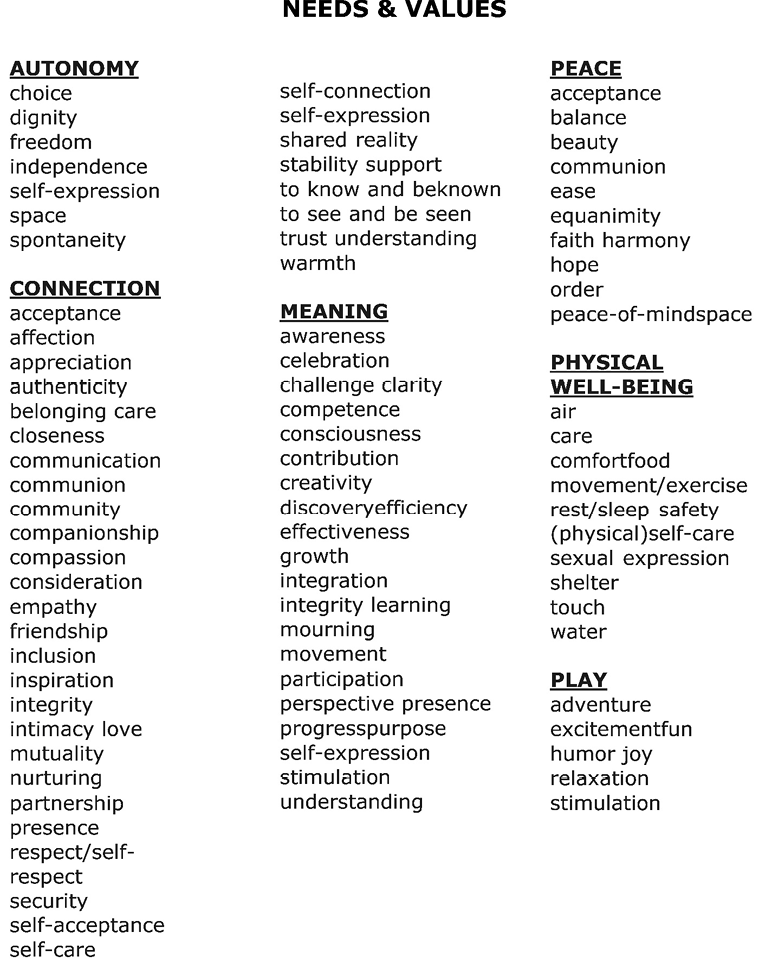

A list of needs can be found in Annex 2, to facilitate their identification.

- It is extremely important not only to express one’s wishes and needs, but also to follow them up with a request. The request should be clear, concrete, precise and positive (to do something, rather not do or to stop doing something) and should relate to the present time. In absence of an explicit request, the interlocutor would not understand what is required from him/her and most probably might think to be responsible for fulfilling the other person’s needs, which might lead to a defensive or complying reaction. When making a request, one could address a request for connection or a request for action. The former is a request for willingness to repeat or rephrase what has been heard, to make sure to have been clear and understood or, alternatively, to share feelings about what has been said. Differently, a request for action refers to a readiness to put something into action that satisfies the needs at stake. Very often, it is necessary to go through a request for connection before one can proceed with a request for action. Hence, in our example, in case the social worker decides to share his/her own feelings and needs with the client, he/she should also express a request addressed to that person. It might be a connection request such as «How do you feel about what I just said?» or «What did you get out of what I just said?», or an action request, like, for example: «Would it be ok for you to look now again together at our next appointments?».

It is crucial that it is a genuine request — one that includes the possibility of receiving a «No» without negative consequences — and not a demand, implying punishment or blame in the event of a negative response. «What determines the difference between a request and a demand is how we treat people when they don’t respond to our request» (Rosenberg, 2005a, p. 47). Moreover, and most importantly, a «No» is an opportunity for further dialogue, as behind it there is always a «Yes» to other needs.

In NVC listening focuses on the process rather than on the content (Larsson & Hoffman, 2015), without knowing where it will lead, similarly to Relational Social Work (Folgheraiter, 2004, 2016, 2017; Folgheraiter & Raineri, 2017). This process is valuable for managing difficult relationships with service users, but also with colleagues, with practitioners from other services, and with one’s own institution, as it will be described below.

The ultimate goal of NVC is to express one’s own feelings, needs and requests with clarity and selfresponsibility, to listen empathically to others’ feelings, needs and requests, and to connect and move together towards solutions and cocreate strategies that will work for all parties involved. The concept could be summarized in «Connection first, before solutions», which also implies that no real solutions are reachable if there hasn’t been any previous real connection.

Listening to oneself or self-empathy

[I]f we’re not able to empathize with ourselves, it’s going to be very hard to do it with other people.

M. B. Rosenberg

Social workers are generally trained to focus on service users and to connect with them, rather than to be in touch and connect with themselves (Rosenberg, 2015). Sometimes, when faced with one’s own emotions, especially if they are unpleasant, such as anger, disgust or frustration, social workers do not stop to listen to them as they manifest, but focus on what others (service users, their families and communities, their organisations, colleagues, other professionals from other services involved in the case, etc.) expect from them, i.e. to be a «good» social worker, empathic, controlled, emotionally detached, lucid and effective. All this is very difficult if one has not first listened to one’s own feelings, and reflected on their meaning, the message they carry and, in NVC terms, the needs they express. The importance of a reflective practice was already highlighted by Donald Schön (1983, 1987). Although this concept is usually referred to in Social Work theory and trainings, it remains largely unimplemented. The reasons for this are often traced back to the workload, but often they rather lie in a professional and organisational culture that does not promote listening to oneself, one’s emotions and needs (Sicora, 2021a, 2023; Gibson, 2014, 2016a, 2016b, 2018).

Actually, the Social Work profession could be more effective and more satisfying for both professionals and service users if, before orienting themselves towards others, social workers oriented themselves inwardly. According to NVC, to connect with another person and give him/her empathy, it is necessary, first of all, to connect with oneself and receive empathy about one’s feelings and unmet needs (Rosenberg, 2005a, p. 70). This empathy can be received from others, or even from oneself in a process that Rosenberg calls self-empathy.

This process follows the four steps described before. It starts with the observation of what has triggered us, moves on to identifying our own feelings about it and the related needs, and ends with the formulation of a request, which can be addressed to others or to ourselves.

In particular, in Social Work it can happen that the professional resonates with the experiences brought by the service user, when confronted with situations similar to those he or she has experienced. The risk of countertransference arises in such cases, if the professional is not aware of what is happening internally (Folgheraiter, 2016).

Similarly, it may occur to be confronted with situations that provoke dissonance and activate prejudices or stereotypes. To be able to interact meaningfully with the service user, it is necessary for the social worker to be aware of his/her feelings and needs and of what has triggered them. Only this way can he/she then truly connect with the other person, with honesty, empathy, and authenticity, because respecting both his or her own feelings and needs and being open to empathically listen to and accept the client’s ones (Rogers, 1961, 1977; Mucchielli, 1998; Folgheraiter, 2011). If there is no listening to the self, the space that is supposed to be open and available for the relationship with the other person, will inevitably remain occupied by unacknowledged feelings and needs. As Morin (1999) writes, there is a need for an apprenticeship to self-observation as part of the apprenticeship to lucidity through a reflective attitude, bearing in mind that the apprenticeship to understanding and lucidity is not only never completed once and for all, but must be continually restarted.

Self-empathy does not necessarily have to be about unpleasant feelings; it can also be about pleasant ones, such as joy, self-efficacy, or gratitude. Recent research conducted in Italy, England, Israel, and South Africa on the subject of positive emotions of social workers have revealed the importance for the latter to reflect on work situations that bring them joy, satisfaction and well-being. This research also highlighted that reflecting on the joy encountered in one’s professional career has the effect of intensifying and multiplying this emotion (Sicora, 2021b), with a reinforcing and motivating effect also on other future situations (Sicora, 2021b, 2022). Furthermore, the sense of wellbeing and satisfaction generated by recognition and success is a positive factor in the psychophysical health of any social worker (Sicora, 2021a, 2023).

Going through, first of all, this process of self-empathy, to become aware of and take responsibility for their own thoughts, feelings and needs and connect with them in a kind and empathic (compassionate, would Rosenberg say) manner, without guilt or shame (Sicora, 2021a, 2023; Gibson, 2014, 2016a, 2016b, 2018), is crucial for social workers to be able to create within themselves an empty and neutral space from where they can connect with service users, truly listen to their feelings and needs and «meaningfully engage in an empathic relationship with the people with whom and for whom they work» (Sicura, 2022, p. 254). In the absence of this process of self-empathy, the risk of resorting to «violent» communication and thus compromising the helping relationship is very high; the client will probably feel criticized, blamed and judged and will most likely react with a defensive or aggressive attitude, or with formal compliance out of fear of the consequences, or out of guilt, shame or duty.

NVC in the helping relationship

Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing, there is a field. I’ll meet you there.

Gialal al-Din Rumi

Having dealt with social worker’s self-connection as a precondition for empathic listening, it is now relevant to focus on how NVC can fundamentally contribute to the helping relationship. NVC shares with the relational approach the values that should guide social worker, such as authenticity, reciprocity, acceptance without judgement, an anti-oppressive and anti-discriminatory approach leading to empowerment (Folgheraiter, 2011, 2016, 2017; Rogers, 1977; Mucchielli, 1998; Dominelli, 2002; Thompson, 2016; Tedam, 2021) and to participation (Calcaterra & Raineri, 2021, 2022; Warren, 2007). These values should underpin the entire process of the helping relationship in all its phases (engagement, assessment, planning, intervention, evaluation, and termination) and in particular in the interview, as its main instrument.

Rosenberg defines empathy as a «respectful understanding of what others are experiencing» (2015, p. 126) and it occurs only when we have successfully shed all preconceived ideas and judgments about them.

NVC assumes that people’s vital energy, and thus their motivation to change, resides in their needs. In the helping process, it is necessary to accompany the person towards listening to him/herself, to explore together which of his or her important needs are met by his or her actions, and whether there might be more effective and safer ways to meet them, without harming or putting anyone at risk.

Alike to the reflective practice (Schön, 1983; Sicora, 2014, 2021b, 2022), Rosenberg urges helping professionals to ask themselves the following questions: «What is this person feeling? What is she or he needing? How am I feeling in response to this person, and what needs of mine are behind my feelings? What action or decision would I request this person to take in the belief that it would enable [him/her] to live more happily?» (2015, p. 259). This process consists of receiving with empathy what the person brings, through attentive, active and respectful listening, and asking him/her the questions and reformulations typical of NVC: «Do you feel...? Do you need...? What I get is that... Is that correct? Is there something else?».

What people bring to social workers are essentially conflicts: these may be internal conflicts or conflicts with families, with the community or the State, or with the social workers themselves. In order to listen empathetically to people and to resolve conflicts using NVC, it is necessary for social workers to train themselves to translate any message into the expression of a need, regardless of how «tragic» and «suicidal» (Rosenberg, 2005a, pp. 28, 29, 68, 122) that expression may be and of the form that this message may take — whether it is silence, denial, criticism, judgement, or perhaps an aggression-laden message. Once the professional senses the client’s possible need, he/she checks it with the client and then helps him/her to put it into words. «If we are able to truly hear their need, a new level of connection is forged — a critical piece that moves the conflict toward successful resolution» (Rosenberg, 2015, p. 213), so fulfilling a true helping relationship paving the way for agreed interventions that are more likely to be sustainable. This process makes it possible to create a space — «beyond the ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing» — in which the social worker and the person can meet to devise strategies together, choosing among those available the ones most suited to meeting the needs of everybody. «The objective of NVC is not to change people and their behavior in order to get our way; it is to establish relationships based on honesty and empathy that will eventually fulfill everyone’s needs» (Rosenberg, 2015, p. 121).

«Power with» versus «power over»

This process is undoubtedly more problematic in cases of referrals — e.g. of child protection — which typically require an exercise of power. At the same time, in such situations, the presence of social workers is intended to ensure an intervention aimed at helping and supporting all parties involved, including those being referred (Folgheraiter, 2016). Keeping this role in mind, NVC asks practitioners to move from a concept of power as «power over» to «power with» people (Rosenberg, 2005a, p. 54). Power over others is a weak power in that the more unilaterally it is exercised, the less decisive and lasting its effects will be. Every time we judge, criticize, blame, humiliate, shame, label, punish, instead of observing, listening to the other’s feelings and needs and expressing our owns; every time we make demands, instead of requests; whenever we leverage fear, guilt or shame, or impose an obligation, instead of being motivated by a desire to contribute and meet the needs at stake, we use violent and non-empathic communication that will break down any possibility of real connection and cooperation and from which further mistrust, resistance, hostility and conflict will arise. «[A]ny time somebody does what we ask out of guilt, shame, duty, obligation, or fear of punishment, we’re going to pay for it», so as everybody else (Rosenberg 2005a, pp. 49, 52).

Certainly, in some extreme cases, social services will need to revert to the use of force. NVC emphasises the importance of the quality and function of this force, by highlighting its protective use instead of its punitive one, a difference that should already be inherent in the role of social workers, which differs from that of the judiciary or law enforcement (Folgheraiter, 2016, p. 286). However, in practice, especially if the social worker has not cleared his or her inner space of prejudices, judgments, or strong feelings such as anger, frustration or disgust, it can be very difficult not to fall back on the punitive use of force, directed at repentance and change through blaming. In the protective use of force, it is assumed that behind the harmful behaviour, for oneself and/or for others, there is some form of ignorance, in particular a lack of awareness of the consequences of one’s actions and, above all, an inability to see how it is possible to satisfy one’s own needs without harming others (Rosenberg, 2015, p. 238). The question to be asked in such cases is not so much «What do I want this person to do that’s different from what he or she is currently doing?», but «What do I want this person’s reasons to be for doing what I’m asking?» (Rosenberg, 2015, p. 245), to bring the focus back to the intrinsic value of the action instead of its external consequences.

Rosenberg stated that «[o]ne of the most powerful ways we’ve found of creating power with people is the degree to which we show them that we’re just as interested in their needs as our own» (2005a, p. 55).

If social workers will be able to maintain the ability to give empathy even when the other person is passively or actively opposing, the latter will be able to feel safe enough to continue exploring with the practitioner his or her deepest needs and to search together for more effective strategies that can meet these needs at a lower cost, without harming anyone, on the assumption that all needs are worthy of value. Agreements reached in this way will be much more likely to be respected by all. In this way, power becomes a common, «relational good» (Folgheraiter, 2016, 2017; Folgheraiter & Raineri, 2017; Donati, 2019).

Aggressiveness and anger

However, especially in presence of clients’ aggressive behaviours expressing active and direct physical or verbal violence (Sicora, 2014) towards social workers, it might be challenging for the latter not to resort to a punitive use of force, by exerting power over the former.

A survey carried out in Italy in 2017 on the phenomenon of aggression towards social workers, promoted by the Italian National Foundation of Social Workers, showed that out of a sample of more than 20,000 social workers interviewed, about 90% had received threats, intimidation and verbal or physical aggression (Rosina & Sicora, 2019; Sicora et al., 2022).

This Italian survey is very important in an international context in which the topic of assaults on social workers is not frequently researched. Exploring this issue is useful not only to increase the safety of social workers, but also to enrich their practices with a reflection on this phenomenon, in order to better understand the experience as well as «in the interest of those who sometimes do violence as a last attempt to oppose what they perceive as a wall of indifference or inadequacy with respect to their requests and needs» (Sicora, 2014, p. 157; Sicora et al., 2022).

These words immediately recall the heart of NVC, which invites to connect with the other person’s needs, regardless of the form those messages take. In aggressive behaviours the dominant emotion is certainly anger. In NVC, anger — as shame and guilt — is considered an «expensive» emotion due to very high price in terms of loss of connection with one’s own true feelings and needs and with the other person and is often linked to an interpretation of the situation and a negative judgement of the other person. Anger arises by thinking others are wrong, which shifts the energy away from wanting to get our needs met to wanting to blame and punish others (Rosenberg, 2005c, p. 12).

On this basis, rather than reacting to anger, social workers should help the person in the grip of anger to identify the needs associated with it and the underlying true feelings, usually of pain, frustration, suffering or concern. Rosenberg’s call not to listen to anger and not to respond to it on that level ties in with his call to receive with empathy and to remain in empathy even when there is aggression. Certainly, in serious cases it will be necessary to resort to the use of force in its protective sense, clearly communicating to the client that any measure that is going to be taken is not directed at punishment, but at protecting the needs of all persons involved, including the ones of the practitioner. In this process, it will be possible to accompany the person in moving from the position «I feel anger because you...» to the position «I feel anger because I...», thereby untying the emotion of anger from external facts and connecting it to internal needs (Rosenberg, 2005c, p. 20). Only then will it be possible to think together about the strategies available to satisfy the needs of which anger is an expression (Larsson, 2012). For example, if a father verbally assaults a social worker by threatening him or her, following a removal order of his child, and blaming the practitioner for this removal, he will probably address a message such as «I’m furious because you are responsible for my child having been taken away from me». The social worker could, instead of defending him/herself, acknowledge this anger and try to guess the needs and feelings underneath. This would be a real helping relationship, in which the parent is supported and accompanied in connecting to his grief to get to say, for example: «I feel desperate because it is important to me to maintain a connection with my child». This will allow the two to think together about strategies to meet that need, which will protect the child at the same time. As Sicora writes, «if violence is a form of communication, listening could be the best form of prevention» (2014, p. 162).

Linked to the possible coresponsibility of violence on the part of social workers themselves (and sometimes of their organisations) — and thus on the ways to prevent violence against them — there is a very interesting line of research, conducted by Matthew Gibson (2015, 2018, 2019a), about the use of guilt and especially shame in English child protection social services, given the «link between shame-proneness — and unproductive ways of managing anger» (Gibson, 2015, p. 335), notwithstanding other possible reactions, like withdrawal, self-harm — (psychologically, by putting themselves down, or physically, also by developing dependencies to numb themselves) or a pleasing one in an attempt to gain acceptance (Gibson, 2015; Tangney et al., 1996).

Shame

Gibson points out «a paradox that exists in social work with children and families. On the one hand the profession is founded on the values of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility, and respect for diversities.1 […] On the other hand, research has identified that many experience child and family social work practice, and in particular child protection, as intimidating, confusing, shaming, and humiliating» (2019a, p. 2).Therefore, he invites and paths the way «toward a shame-reducing social work practice» (2015, p. 339).

What practitioners should take into account is that they will probably be dealing with persons who are already affected by guilt and shame, merely because of being in contact with social services, all the more so in the field of child protection, where the assessment of parenting skills is often part of the process.

In NVC both the emotions of guilt and shame are also defined as «expensive» (so as anger) and they both stem from a negative self-evaluation. The difference between the two is that, whereby guilt is felt in relation to negative judgements about one’s specific behaviour («I did something wrong»), shame is felt when one makes negative internal judgements about oneself («I am bad») (Gibson, 2015, 2016a; Lewis, 1971). The consequences of this are that, while guilt considers the other’s perspective and may lead to a desire to apologize or repair and hence to prosocial behaviours, shame is a much more painful emotion involving the belief of being inadequate, flawed, «small, worthless and powerless with a desire to hide, escape or strike back» (Gibson, 2015, p. 334).

Research has shown, on the one hand, a correlation between the feeling of shame and acts of anger, hostility, aggressiveness and a strong resistance to engagement and cooperation and, on the other hand, a negative correlation between shame and the capacity for empathy. Moreover, the feeling of shame is often combined with emotional, mental or behavioural disorders such as to characterise the users as «difficult» (Gibson, 2015; Tangney et al., 1996; Tangney & Dearing, 2004).

Therefore, to prevent resistance, withdrawal, hostility and/or violence and seek co-operation, it is essential for social workers to avoid attitudes, behaviours and language that could induce or reinforce the feeling of shame. Shaming practices have shown themselves as not able to create (a real) compliance and thus as ineffective, besides violating moral obligations (Gibson, 2019a). In child protection, «[individuals] experiencing shame will be focused on themselves, inhibiting a focus on the child, resulting in behaviour which seems unconcerned with the child’s distress. From their perspective, they may be attempting to hide their "bad" self from the judgement of others, contributing to the avoidance, manipulation or stage management» (Gibson, 2015, p. 337).

Disguised compliance, aggression or avoidance are usually consequences of an exertion of power over the service user, through a controlling attitude against the lack of cooperation (Reder, Duncan, & Gray, 1993; Gibson, 2015). Cooperation is closely linked with the topic of participation, which has been widely explored by Calcaterra and Raineri (2021, 2022), not only in reference to children but also to their families, and especially in the field of child protection. They highlighted recurring communication difficulties between professionals and service users and the risk of the former presenting paternalistic attitudes (power over) that seem to open up spaces for participation but that in reality seek mainly to a formal compliance, in which parents feel they have no decision-making power. This is despite the clear advantages of participation leading to more effective interventions that are more responsive to the needs of the parties concerned.

In the context of this discourse on power, it’s also worthwhile mentioning the practice of Restorative Circles. They were devised by Dominic Barter, an international expert in Dialogical System Design and Restorative systems, in the 1990s in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro to support people in conflict, using existing practices within the community to respond to conflict through dialogue. It is a community and participatory approach with the co-presence of all the people involved and a facilitator. In regenerative circles, all participants renounce their social roles and simply participate as human beings. This approach has been strongly influenced by Paulo Freire and by Rosenberg; not surprisingly Dominic Barter has been a long-time student and colleague of Rosenberg and has worked as NVC Trainer for many years.

A practical example of regenerative circles specific to social work are the Family Group Conferences (FGCs), imported from New Zealand in relation to the experience of local social services with the Maori families, whose children were removed without the involvement of all family members. FGCs are based precisely on a concept of participation, shared power, respect for identity and diversity, individual self-determination, and personal dignity. The Family Group Conference consists of a decision-making process involving formal meetings in which the members of the extended family and all professionals involved in the case take part, in the presence of a facilitator. The core of the process lies in the elaboration of an intervention plan by the family itself that satisfies all FGC participants. FGCs are nowadays implemented in many countries, including Italy (Maci, 2017).

These models and practices are very much an expression of Rosenberg’s declared wish and purpose for social change, which he considered the ultimate goal of NVC, alongside inner change and the development of more humane and compassionate relationships (Rosenberg, 2004).

Especially in child protection cases, service users consider it crucial to receive empathy and acceptance from professionals. Parents who feel treated as persons with their own rights and needs, and not just as inadequate parents, report greater satisfaction with services (Gibson, 2015). Smithson and Gibson (2016) found that for parents involved in child protection system the threat of consequences silenced them. They «felt unable to speak out or challenge the things they disagreed with or coerced into signing agreements they did not agree to. Such experiences related to a sense that they were being treated as "less than human"» (p. 2).2

If social workers fail to empathically recognise people’s highly negative, and ultimately harmful, beliefs about themselves, they may unintentionally validate and reinforce them. Interventions stemming from this attitude will increase the recipients’ sense of inadequacy, worthlessness, and incompetence, i.e. the opposite of their empowerment and of the objective of social work, that should aim to support parenting skills. This can have a devastating impact both in terms of cooperation and for the effectiveness of the interventions, especially if children are involved. For these reasons, on one hand, even greater empathy would be needed on the part of social workers towards «difficult» service users, and they should pay a particular attention to exerting power with them, instead of over them. On the other hand, organisations and management, policymakers and legislators should take responsibility for trainings and supervisions dealing with this subject, to support practitioners and build their capacities to better understand, acknowledge and deal with service users’ feelings of shame (Gibson, 2015, p. 339).

Burnout prevention

Not listening to or accepting one’s own unpleasant feelings that arise in the helping relationship or in the relationship with colleagues or other professionals or in the organisational context intensifies fatigue and increases the risk of burnout (Sicora, 2021a). Classic signs of burnout are, among others, a growing emotional and mental exhaustion and an increasing sense of disconnection from oneself and others (Glouberman, 2002), also called «depersonalization» (Maslach, Jackson & Leiter, 1996). Burnout tends to especially affect helping professionals, that are particularly exposed to emotionally draining situations. Alongside emotional exhaustion, they tend to develop negative perceptions and feelings about their clients (Maslach, 1976, 1993; Schaufeli, Leiter, & Maslach, 2009).

NVC is an invaluable tool against burnout as it invites precisely to selfempathy or to ask others for empathy to reconnect with one’s own feelings and needs; it invites to a reflective practice, allowing professionals to reflect on their emotions in order to reattribute meaning to their actions (Sicora, 2021b).

Rosenberg himself mentioned «[p]revention of "burn-out"», «[r]equesting the necessary support to serve others» and «[remaining human when institutional forces encourage competition, coercion, and dehumanization» as three of the many positive effects of trainings in NVC to health care providers (Rosenberg & Molho, 1998, p. 340; see also Larsson, 2017).

However, especially for the purposes of combating work distress and preventing burnout — which are typically organisational phenomena — self-empathy should not entirely replace practices that involve the organisational context. Organisations should promote a «culture of listening», whereas in those contexts it is more common to discuss managing emotions rather than reflecting on emotions (Sicora, 2021a). It is therefore not surprising that social workers are more committed to trying to manage their emotions than to listen to them with empathy and without judgement, welcoming them as guides towards their own needs and consequently towards their actions.

These considerations seem to be confirmed by German research (Wacker & Dziobek, 2018) showing that NVC training to professionals who work in emotionally demanding areas, such as health care workers, can prevent their occupational distress in dealing with patients — here defined as «empathic stress» which can lead to burnout — as well as in dealing with colleagues and supervisors. The conclusions drawn from the research findings can be extended to all helping professions, including social workers. In particular, with regard to the empathic stress, it was found to have decreased after three months after the NVC training, which, according to the researchers, would support the thesis that NVC is an effective method of managing one’s feelings in the context of emotionally intense interactions, thanks to the acquired ability to observe unpleasant situations of others in a nonjudgmental manner, with awareness of one’s own feelings and needs.

NVC in professional relations

Relations with colleagues and other professionals

In light of what has been said so far, it is easy to deduce how NVC can also have very positive effects on social workers’ interactions with colleagues and with professionals from other services. This seems very relevant considering the inter-professional conflicts or at least tensions that social workers often encounter in their profession.

In this sense, receiving training within a service to provide homogeneous communication tools could be very useful in improving interactions, mutual understanding, collaboration, and ultimately the interventions towards service users. The value of NVC in identifying the needs underlying feelings such as frustration, anger, a sense of helplessness, fatigue, or distrust, which can also emerge in relationships between colleagues, was highlighted by the above-mentioned 2018 German research (Wacker & Dziobek, 2018). That same research also highlighted the effectiveness of a training in NVC to reduce work stressors arising from relationships with colleagues and supervisors, due, on one hand, to an improved ability to verbalise unpleasant feelings during confrontational group discussions, and, on the other hand, to better communication skills in performing daily tasks.

Rosenberg mentioned in his books many examples referred to work situations in which NVC proved to be very useful to solve conflicts, find solutions, reach agreements and eventually to increase professionals’ effectiveness and wellbeing. The above-mentioned paper on NVC training to health care providers (Rosenberg & Molho, 1998) outlines its value for those professionals «to facilitate the flow of information necessary for people to work cooperatively together and resolve differences effectively» (p. 335). Indeed, similarly to social work, this is a professional field in which communication with service users and cooperation between team members are crucial for the effectiveness of the services. In particular, the two authors point out how training in NVC can contribute to «[b]uilding cohesive work teams», «[r]esolving conflicts within and between work teams», «[i]ncreasing the effectiveness of meetings», «[s]taying connected to the human being behind titles» and to «[r]emembering what is important when under pressure» (p. 340).

An article entitled «Improving interprofessional collaboration: The effect of training in Nonviolent Communication» (Museux et al., 2016)3 focuses precisely on interprofessional collaboration between health professionals and social workers. Researchers (from both areas) from Quebec, Canada, carried out a study in 2013 with two interprofessional teams from social and health services for families and young people, to measure the effects of a seven-hour NVC training. Results revealed «improvements in individual competency in client/family-centered collaboration and role clarification, […] in group competency […] with respect to teams’ ability to develop a shared plan of action» (p. 1), and in developing collective leadership thanks to a better awareness and management of their own and others’ emotions. In particular, the acquisition of a common language — respectful of everyone’s needs — was considered all the more important since people came from different professions. Furthermore, the training participants appeared to understand the importance of self-empathy to be able to give empathy to colleagues and to tune in to the empathy needs of others during work meetings. They also experienced a greater sense of cooperation, belonging and authenticity, which are fundamental conditions for developing the mutual trust needed to work together.

This seems very relevant considering that interprofessional communication difficulties can generate conflict and stress and are considered the main causes of professional errors and delays, as well as work fatigue and burnout.

More recent research (Mann, Lown, & Touwn, 2020) focused on a training in NVC (there called Compassionate Communication) to improve interprofessional teamwork on a labour and health unit. This training resulted in increased staffs’ perceptions of treating each other with respect and a stronger sense of being part of a team. There were also significant changes related to self-reflection and self-awareness about having some feelings, but, interestingly enough, many respondents stated to feel often confused about their actual feelings about things, which shows the extent to which greater investment in such trainings is needed. Overall, the NVC training showed itself as beneficial in improving a culture of respect and interprofessional teamwork.

NVC within organisations

As already mentioned, for the wellbeing of service users and practitioners and ultimately for the effectiveness of the interventions, it’s important to import concepts such as non-judgmental listening to one’s own and others’ feelings and needs, and honest, authentic, connected, and collaborative communication (all NVC building blocks) into organisational contexts. The responsibility to promote these values and competences and a reflective practice falls on the organisations themselves. Sicora states that «[t]he role of organisations is essential for the effective use of emotion in judgement and decision making. [A] stronger focus on responsibility and reflective organisations is important to reduce the influence of the blame culture» (2023, p. 29). He also questions whether organisations might «subtly evoke violent aggression in those that are not capable of making their voices heard and how much dynamics of oppression [are] still hidden within some organisations» (2014, p. 162).

Similarly, Gibson has researched the subject of shame as a feeling experienced not only by service users, but also by social workers, as induced by their organisations (2014, 2016a, 2016b, 2018). What emerged from this line of research was that social workers’ emotions of shame, guilt, humiliation and pride were correlated with expectations of the organisational context. Thus, the professional practice of individual social workers could be categorised on the basis of their degree of identification with or resistance to these expectations: from implementing them or conforming to them in the absence of identification, to seeking compromise or dissimulating acts of resistance, to confronting management in an attempt to change these expectations. Moreover, the selfconscious emotions which are related to the social workers’ positioning in relation to the practices of the organisational context have an obvious repercussion on their relationships with service users.

Another interesting research consisting in providing an intensive six-month training in NVC (in this research called «Collaborative Communication», with a focus on the absence of the control dimension) to several business managers, evaluated its effects in terms of the quality of relations and communication and the efficiency and effectiveness of the ones being trained and of the teams they were responsible for. The interest in this research lies in the fact that it translates many NVC concepts into a language that is functional to the dynamics of an organisational contexts.

Results showed that, following the training, the managers had noticed an increase in the effectiveness of conversations and meetings. Although NVC practice initially seemed to slow everybody down to make sure that the conversation was given the time and respect it deserved, participants reported that using NVC ultimately brought to better results faster, and that with practice conversations themselves got quicker (p. 16). In addition, there was an improvement in their ability to communicate clearly, to formulate direct requests to solve problems, to understand the views of others, to speak openly in a straightforward manner, to mediate conflicts between team members and to facilitate effective meetings.

Through the use of NVC and in particular of empathic reformulation, people felt more heard in a way that changed the course of the conversation. Another outcome was an increased focus and effectiveness in achieving «mutual solutions» where no one had to compromise by sacrificing needs and everyone felt satisfied. The training had also helped to increase mutual respect for each other’s opinions, creating a non-judgmental environment where everyone could feel free to express them. Trust and cohesion in pursuing shared goals also improved. Some participants also emphasised that NVC had helped them to work with respect for diversity and with people from different cultures. Greater commitment of the staff members was also noted, in addition to better worklife balance and greater personal well-being.

All these results are consistent with Rosenberg’s calls on dismantling what he calls «domination structures» «as organized control over others» (2005a, p. 37), a concept closely related to antioppressive and anti-discriminatory social work (Dominelli, 2002; Thompson, 2016; Tedam, 2021).

Conclusion

In the light of the above, Nonviolent Communication can strongly contribute to bringing social workers, as individual professionals, and social services, as organisational contexts, back to the heart of the profession understood as its vital centre, that is what makes it deeply humane and based on empathy. NVC reflects the «overarching principles of social work», being «respect for the inherent worth and dignity of human beings, doing no harm, respect for diversity and upholding human rights and social justice», as stated by the Global Definition of Social Work (2014).

Despite the fact that in social work trainings these concepts are constantly repeated, and the interview is rightly indicated as the main professional tool, in practice there is a strong risk of transforming the profession of social worker into that of «social administrator», as highlighted by Gibson (2016c). A crucial role in this sense is played by organisations, which may push in the direction of giving more value to procedures and objectives, than to the helping relationship. «It is essential for social workers and institutional representatives to resume their professional mandate of advocacy with individuals and communities and to oppose policies that reinforce inequalities and exclusion» (Sicora et al., 2022).

NVC shares the belief that social problems are generated by social relations and therefore can only be solved if the social relations structuring a situation or a context are changed (Folgheraiter, 2004). To this aim, NVC «can contribute to our attempts to bring about change […] within ourselves, […] in people whose behaviour is not in harmony with our values, [and] in the structures within which we’re living» (Rosenberg, 2005a, p. 59) and working, I would add. It offers tools to bring about change in human relations to create both quality connections with others, no matter if service users or colleagues, as well as social change, which — it’s worth mentioning — is expressly included in the 2014 Global Definition of Social Work.

For Rosenberg, the process towards social change «begins with working on our own mindsets, on the way we view ourselves and others, on the way we get our needs met. This basic work is in many ways the most challenging aspect […] because it requires great honesty and openness, developing a certain literacy of expression, and overcoming deeply ingrained learning that emphasizes judgment, fear, obligation, duty, punishment and reward, and shame» (Rosenberg, 2005a, p. 10).

However, Rosenberg warns how expressing, or supporting in expressing, clear observations, feelings, needs and requests becomes only a technique if these steps are not intentionally taken to connect emphatically with the other person in a way that allows us to see his/her beauty and the life that’s alive in them. This intention is very different from trying to understand the others, placing us beside, rather than with them.

All this is very relevant for social workers. During their initial training to become such, students continuously told about the importance of empathy in helping relationships, but, in reality, they are often not truly provided with the tools to do that and with the necessary practice. Also, once working, social workers are often overwhelmed with an overload of cases and of administrative tasks that risk disconnecting them not only from service users, but also from themselves and their professional mission. To prevent these risks and face these issues, it would be extremely important to include NVC workshops — based both on theory as on practice — both in the initial training curricula, as in the context of lifelong training and supervisions. These trainings and supervisions should not just target social workers to support them in their casework and community work, but also those in organisational and managerial positions, in order to bring about changes in organisational contexts.

Moreover, to support such initiatives, it would be very useful to carry out research to measure the effects and the impact of such trainings and supervisions, and of applying NVC within social services — possibly building on already existing research in other fields — in relation to the wellbeing and satisfaction of both service users and social workers themselves.

References

Calcaterra, V., & Raineri, M. L. (Eds.) (2021). Tra partecipazione e controllo Contributi di ricerca sul coinvolgimento di bambini e famiglie nei servizi di tutela minorile. Trento: Erickson.

Calcaterra, V., & Raineri, M. L. (2022). La partecipazione di bambini, ragazzi e famiglie nei servizi di tutela minorile: le rappresentazioni degli operatori sociali. Studi di Sociologia, 4, 685-706.

Donati, P. (2019). Discovering the Relational Goods: Their Nature, Genesis, and Effects. International Review of Sociology, 29(2), 238-259.

Dominelli, L. (2002). Anti Oppressive Social Work Theory and Practice. London: Red Globe Press.

Ferguson, H. (2009). Performing child protection: Home visiting, movement, and the struggle to reach the abused child. Child & Family Social Work, 14, 471-480.

Folgheraiter, F. (2004). Relational Social Work. Toward Networking and Societal Practices. London: Jessica Kingsley.

Folgheraiter, F. (2011). Fondamenti di metodologia relazionale: La logica sociale dell’aiuto. Trento: Erickson.

Folgheraiter, F. (2016). Teoria e metodologia del servizio sociale. La prospettiva di rete (3rd ed.). Milan: FrancoAngeli.

Folgheraiter, F. (2017). The sociological and humanistic roots of Relational Social Work. Relational Social Work, 1(1), 4-11.

Folgheraiter, F., & Raineri, M. L. (2012). A critical analysis of the social work definition according to the relational paradigm. International Social Work, 55(4), 473-487.

Folgheraiter, F., & Raineri, M. L. (2017). The principles and key ideas of Relational Social Work. Relational Social Work, 1(1), 12-18.

Freymond, N. (2003). Mothers’ Everyday Realities and Child Placement Experiences. Waterloo, Canada: Partnerships for Children and Families Project.

Gibson, M. (2014). Social Worker Shame in Child and Family Social Work: Inadequacy, Failure, and the Struggle to Practise Humanely. Journal of Social Work Practice, 28(4), 417-431.

Gibson, M. (2015). Shame and guilt in child protection social work: New interpretations and opportunities for practice. Child and Family Social Work, 20, 333-343.

Gibson, M. (2016a). Social worker shame: A scoping review. British Journal of Social Work, 46, 549-565.

Gibson, M. (2016b). Constructing pride, shame, and humiliation as a mechanism of control: A case study of an English local authority child protection service. Children and Youth Services Review, 70(C), 120-128.

Gibson, M. (2016c). Social worker or social administrator? Findings from a qualitative case study of a child protection social work team. Child and Family Social Work, 22(3), 1187-1196.

Gibson, M. (2018). The role of pride, shame, guilt, and humiliation in social service organisations: A conceptual framework from a qualitative case study. Journal of Social Service Research, 45(1), 112-128.

Gibson, M. (2019a). The shame and shaming of parents in the child protection process: Findings from a case study of an English child protection service. Families, Relationships and Societies, 9(2), 217-233.

Gibson, M. (2019b). Pride and Shame in Child and Family Social Work: Emotions and the Search for Humane Practice. Bristol: Policy Press.

Glouberman, D. (2002). The Joy of Burnout. Isle of Wight: Skyros Books.

IFSW (2014). Global definition of social work. Available online https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/

Larsson, L. (2012). Anger, Guilt and Shame: Reclaiming Power and Choice. Svensbyn: Friare Liv.

Larsson, L. (2017). Human Connection at Work: How to use the principles of Nonviolent Communication in a professional way. Svensbyn: Friare Liv.

Larsson, L., & Hoffman, K. (2015). Cracking the Communication Code. Svensbyn: Friare Liv.

Lewis, H. (1971). Shame and Guilt in Neurosis. New York: International Universities Press.

Maci, F. (2017). Come facilitare una Family group conference. Trento: Erickson.

Mann, J., Lown, B., & Touw, S. (2020). Creating a culture of respect and interprofessional teamwork on a labor and birth unit: A multifaceted quality improvement project. Journal of Interprofessional Care. Available online DOI: 10.1080/13561820.2020.1733944.

Maslach, C. (1976). Burned-out. Human Behavior, 9, 1622.

Maslach, C. (1993). Burnout: A multidimensional perspective. In W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, & T. Marek (Eds.), Professional Burnout: Recent Developments in Theory and Research (pp. 19-32). Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). MBI: The Maslach Burnout Inventory: Manual. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press.

McCaffrey, R., Hayes, R. M., Cassel A., Miller-Reyes, S., Donaldson, A., & Ferrell, C. (2012). The effect of an educational programme on attitudes of nurses and medical residents towards the benefits of positive communication and collaboration. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(2), 293-301.

Morin, E. (1999). La tête bien faite. Repenser la réforme, réformer la pensée. Paris: Seuil.

Mucchielli, R. (1998). L’entretien de face à face dans la relation d’aide. Paris: ESF éditeur.

Museux, A. C., Dumont, S., Careau, E., & Milot, É. (2016). Improving interprofessional collaboration: The effect of training in Nonviolent Communication. Social Work in Health Care, 55(6), 427-439.

Reder, P., Duncan, S., & Gray, M. (1993). Beyond Blame. London: Routledge.

Rogers, C. (1961). On Becoming a Person: A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Rogers, C. (1969). Freedom to Learn. Columbus: Charles E. Merrill Publishing Co.

Rogers, C. (1977). On Personal Power: Inner Strength and Its Revolutionary Impact. New York: Delacorte Press.

Rosenberg, M. B. (2004). The Heart of Social Change. Encinitas: PuddleDancer Press.

Rosenberg, M. B. (2005a). Speak Peace in a World of Conflict. Encinitas: PuddleDancer Press.

Rosenberg, M. B. (2005b). Being me, Loving you. A practical guide to Extraordinary Relationships. Encinitas: PuddleDancer Press.

Rosenberg, M. B. (2005c). The Surprising Purpose of Anger. Encinitas: PuddleDancer Press.

Rosenberg, M. B. (2015). Nonviolent Communication. A Language of Life (3rd ed.). Encinitas: PuddleDancer Press.

Rosenberg, M. B., & Molho, P. (1998). Nonviolent (empathic) communication for health care providers. Haemophilia, 4(4), 335-340.

Rosina, B., & Sicora, A. (Eds.) (2019). La violenza contro gli assistenti sociali in Italia. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2009). Burnout: 35 Years of research and practice. Career Development International, 14, 204-220.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Sicora, A. (2014). Aggression towards helping professions: Violence as communication, listening as prevention? Argumentum, 6(2), 154-165.

Sicora, A. (2021a). Emozioni nel servizio sociale. Rome: Carocci.

Sicora, A. (2021b). Gioia e benessere negli assistenti sociali. Prospettive sociali e sanitarie, 4, 41-44.

Sicora, A. (2022). Emotions in Social Work Education: Tools and Opportunities. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 14(1), 151-168.

Sicora, A. (2023). Blame and emotion in professional judgement. In B. J. Taylor, J. D. Fluke, J. C. Graham, E. Keddell, C. Killick, A. Shlonsky, & A. Whittaker (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Decision Making, Assessment and Risk in Social Work (pp. 23-32). London: Sage.

Sicora, A., Nothdurfter, U., Rosina, B., & Sanfelici, M. (2022). Service user violence against social workers in Italy: Prevalence and characteristics of the phenomenon. Journal of Social Work, 22(1), 255-274.

Smithson, R., & Gibson, M. (2016). Less than human: A qualitative study into the experience of parents involved in the child protection system. Child & Family Social Work, 22(2), 2017, 565-574.

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. (2004). Shame and Guilt. New York: Guilford.

Tangney, J. P., Wagner, P. E., Barlow, D. H., Marschall, D. E., & Gramzow, R. (1996). The relation of shame and guilt to constructive vs. destructive responses to anger across the lifespan. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 797-809.

Tedam, P. (2021). Anti-Oppressive Social Work Practice. Exeter: Learning Matters.

Thompson, N. (2016). Anti-Discriminatory Practice: Equality, Diversity and Social Justice. London: Palgrave.

Wacker, R. & Dziobek, I. (2018). Preventing empathic distress and social stressors at work through Nonviolent Communication training: A field study with health professionals. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 141-150.

Warren, J. (2007). Service User and Carer Participation in Social Work. Exeter: Learning Matters.

Lamedica, F. (2023). Nonviolent Communication in Social Work. Relational Social Work, 7(2), 69-93, doi: 10.14605/RSW722305.

Relational Social Work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License

Annex

Annex 1

Annex 2

Annex 3

The Four-Part Nonviolent Communication Process

|

Clearly expressing how I am without blaming or criticizing. |

Empathetically receiving how you are without hearing blame or criticism. |

OBSERVATIONS |

|

|

|

FEELINGS |

|

|

|

NEEDS |

|

|

|

|

|

REQUESTS |

|

|

|

Rosenberg, 2015, p. 282.

1 I would add «self-determination».

2 «Freymond (2003) identified that the most common labels in the literature associated with service users were "untreatable", "unresponsive", "inadequate", "dangerous", "unwilling" or "unable" to provide care for their children. Such a vocabulary will only exacerbate feelings of shame as service users feel treated in a manner inconsistent with who they would like to be» (Gibson, 2015, p. 337).

3 See also the bibliography cited therein, including, in particular, McCaffrey et al. (2012) on trainings on positive communication and collaboration to nurses and doctors, highlighting improvements in communication through active listening.