The relational foundation of Social Work

Fabio Folgheraiter

Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy

Maria Luisa Ranieri

Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Milan, Italy

CORRESPONDENCE:

Maria Luisa Ranieri

e-mail: marialuisa.raineri@unicatt.it

Abstract

The connection between Social Work and social relationships can be seen as obvious, but it is complex indeed. The aim of this article is to explore several analytical concepts for a better understanding of the deeply «social» (relational) nature of social work practice. Some fundamental semantic, epistemological, and methodological issues regarding this relationship are briefly explored, with particular attention to the dynamics of networking in coping processes. The background of the paper includes general considerations about the scientific nature and «epistemological object» of Social Work, as well as about the discipline’s best place in the ongoing debate between the classical paradigms of determinism on the one hand and of phenomenology on the other. The ambivalent meanings that the widely used term «social» can assume within the label of «Social Work» are analysed, and the different possible connotations of the term «relationship» are discussed. A set of operational coordinates is proposed to better understand what relational (or relationship-based) professional Social Work is and eight levels of relationality in Social Work professional practice are proposed, based on the idea of reciprocity.

Keywords

Reciprocity, Relational Social Work, Relationship-based Social Work, the «social» of Social Work.

Introduction

This article aims to discuss the link between Social Work and social relationships. This link is so close that the two concepts seem to merge. Social work is — at its core — «relational» (or «relationship-based»), as so many authors have pointed out in various ways throughout the history of social work (among others: Hamilton, 1940; Biestek, 1957; Hollis, 1964; Ferard & Hunnybun, 1962; Butrym, 1976; Howe, 1998; Schofield; 1998; Trevithick, 2003; Folgheraiter, 2004; Ruch, Turney, & Ward, 2018). Indeed, every social worker is by definition a relational worker, because — as we will discuss — the terms «social» and «relational» are largely synonymous.

Of course, social workers are not the only professionals immersed in relationships. Every welfare or helping practitioner is immersed in relationships and needs relationship skills (Howe, 1998). Every physician, nurse, psychotherapist, counsellor, every care worker — all professionals who provide or promote some form of human help — must operate within the «code» of relationships.

The term «help» is a relational one. Many other words in everyday use are relational: for example, «mom» or «uncle» or «teacher», to name but a few. These words are relational because they cannot stand alone, so to speak. They only make sense when they refer to at least two parts doing something together: I am a father referring to my children; I am a teacher referring to my students, and so on. The term «help» also has a meaning that is based on a connection between two parts. Helping always involves someone in need and someone willing to help.

For a social worker, however, this «one to one» scheme, if taken literally, feels narrow. While other helping professionals deal with relationships mainly for opportunistic or functionalist reasons — to solve concrete problems in a concrete individual — social workers deal with relationships because they relate to relationships as such, that is: in a «plural» and essential way. So, in this sense, we should say that while all social workers are helping workers, not all helping workers are social workers.

In Social Work literature, there are some models and approaches called «relational», for example Relational Social Work by us and our colleagues (Folgheraiter, 2004; 2007; Folgheraiter & Raineri, 2019; Cabiati, 2017; Calcaterra, 2017; Panciroli, Corradini, & Avancini, 2019; Corradini, Landi, & Limongelli, 2020), or Relationship-based Social Work by Ruch and colleagues (Ruch, 2005, 2009; O’Leary, Tsui, & Ruch, 2013; Ruch, Turney, & Ward, 2018). In line with what we wrote so far, these labels could be seen as oxymorons, as redundant and self-evident formulas. It that so? We think it is not. Social workers are social/relational professionals for some interesting reasons which — as argued a decade ago in The Mystery of Social Work (Folgheraiter, 2012) — remain curiously unclear. We will try to explore this topic by dividing it into three broad Sections, dealing whit semantic, epistemological, and professional issues.

Some semantic issues

Unfortunately, in Social Work we play with some «sacred» words that are often used in a broad and automatic way. We say «social», «relationship», «help», «networks», «systems», «service users» and so on, in a very careless way. There is a kind of agreement that leads us to take the meanings of these words for granted. When someone asks us to explain what we mean, we may be surprised and annoyed.

St. Augustine discussed this semantic paradox in his Confessions. He pointed out that many of the words we pronounce every day seem so clear, but their meanings are extremely obscure, and their explanation abstruse.1 Augustine was thinking about the concept of past, present, and future time, expressed in words we use continuously in our everyday language.

In Social work theory, two basic and very common words need to be discussed: the word «social» and the word «relationship».

What does «social» mean in «Social Work»?

In an interesting article published many years ago, Martin O’Brien (2004) asked: what is social about social work? The same question is asked by Adams, Dominelli and Payne (2009) in their introduction to an important anthology. Here, to better understand the subtle semantics of the term «social», we propose to consider that it can be used both as an adjective and (although less frequently) as a noun. Depending on this, the term «social» takes on different meanings.

(a) «Social» as an adjective

In this case, the term «social» simply qualifies the work of social workers and highlights its «main quality». It tells us that this «work» is something that is good for society, a service to the community, a meritorious work done in the general interest. The adjective «social» expresses the general (sociological) impact of the micro-actions of social workers.

Parton (2002, 2008), building on Donzelot (1988) and Hirtsh (1981), identifies the «social» as a hybrid area between the private and public spheres. Social work developed to act just in this hybrid space, dealing with «private» difficulties that were nevertheless of general relevance, because the welfare state had taken on the duty to deal with them, but without undermining the responsibility of individuals and families.

Of course, this meaning (Social Work is «social» due its utility for the general society) could be potentially misleading. In fact, if something that is useful to a society is «social», then we can say that everything is «social». Any human art or craft is clearly social. A shoemaker, a lawyer or a priest helps society to function. Even more «social» are the helping professionals: a psychologist or a nurse or a psychiatrist or many others. In their daily work, each of them adds small pieces to the big puzzle of general well-being. So, we would say: all those who contribute to the well-being of society are of course «social agents», but clearly not «social workers».

(b) «Social» as a noun

In Social Work, the term «social» can also suggest a counterintuitive meaning, subtle and perhaps difficult to understand, but rich and inspiring, especially for social work researchers. We can read it as a noun. This usually refers to a subject (that is: to a someone who does an action). An adjective simply qualifies or embellishes a particular «thing» (a particular «entity»). A noun identifies an entity itself. In a perhaps bizarre way, we can say that «Social Work» here means:

a «social» that is working

or, the same:

a work done by a «social».

The «social» here is precisely the subject who performs the act of caring.

Historically, this insight can be traced back to a study published in the French magazine «Esprit» in the Seventies of the last century. Domenach and coll. (1972) wrote that: «Le travail social c’est le «corps social» en travail».2

According to this insight («Social Work is the "social" that work»), we should understand that social workers don’t perform the «Social Work» on their own. To develop care and well-being, the whole «social» must work.

If the subject that does Social Work is not an individual professional or a welfare organisation, the question is: how should we define this «social» more precisely?

Domenach and coll. (1972) were not so clear on this point. In our view, the «social» is not the «social body», as in their expressions. It is not the «body of the great society», the whole of society. The «social» is not the large, comprehensive, impersonal machine studied by macro-sociology. Indeed, social workers are only partly sociologists.

So, what is the social about Social Work? We try to offer a brief definition:

The «social» in Social Work is any small set of associated people (a group, a network, a web of social relationships) that can be clearly distinguished and identified within the jumble of overall social relationships of a community or society.

The «social» is a specific part of the larger society. It is an enclave formed by relationships between real people who share sufferings and problems, but who also share useful concerns, motivations, and strengths. In Social Work terms, this «social» is often depressed, blamed, and oppressed, but it is also to some extent resilient and proactive. This «social» wants to address difficulties, think about and plan for the future, in the hope of making progress in their wellbeing and human development. This specific «social» can be described as a «coping network» (Folgheraiter, 1998), i.e., a social aggregation in which several associated people identify and pursue a common aim. This concept resonates that of «communal coping», as proposed by psychologists Lyons, Michelson, Sullivan and Coyne (1998).

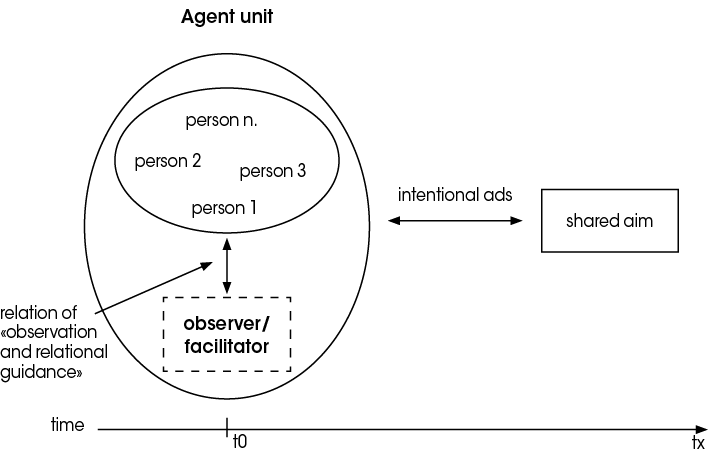

To represent a coping network, we have for a long time used a graphic scheme (Figure 1), built for educational, training and research purposes. We called it Social Stave (to evoke the romantic possibility of «reading» social dynamics as «music»). This scheme represents a «social» (including an «observer» or a «facilitator» of it) working toward a shared aim. It’s a small human network involved in associated, future-oriented, coping activities — catalysed by a common hope.

What is this hope, what is this shared aim? We’ll come back to these questions later.

Figure 1 The Social Stave: A graphic scheme of a coping network.

What does «relation» mean in Social Work?

Another term often used — not always clearly — is «relationship». As mentioned above, it is at the heart of any discourse about Social Work (Trevithick, 2003). For a better understanding, as Winter (2019) suggested, we need to get over the common-sense idea that being «relational» means being a gentle, soft, diplomatic, smiling, genuine social worker. In a rigorous academic discourse, we need to keep in mind a fundamental analytical distinction: The «social relation» as bonding and the «social relation» as shared action (Donati, 2013).

(a) Social relationship as a bond

When we think of the social relationship as a bond, we think of two or more people who have significant ongoing interactions, who have a strong sense of each other’s presence, who enjoy and benefit from being together. Bonding is a kind of imaginary cement that holds people together and forms the cells of society. In doing so, it makes human beings the «social animals» of which philosophers Aristotle speaks (Newman, 2010).

Social bonds create «social support» — a sense of intimacy and security that forms the emotional and practical basis of our lives and — when needed — the basis of our relevant hopes for help or recovery.

Many «historical» representations of social networks — for example, Bronfenbrenner’s ecological map (1979), or the ecomaps by Hartman (1978), or by Gitterman and Germain (2008), or the Todd’s Ego-Network scheme (1979) — are based on this structuralist idea of the relationships as a social bond.

(b) Social relationship as shared action

In our Social Stave schema, social relationships or — more generally — social networks, are considered in a «dynamic» view: That is, as shared actions.

In this view, the «social relationship» is viewed as a «joint agency» expressed by two or more individuals with different strengths, needs, hopes, ideas, intelligence. Each of the different individuals brings their original contribution to the interaction, so that a common transformative/generative action emerges.

According to Donati (2019), there is a «third effect» that emerges from the interaction of human subjects with different strengths. This «third effect» is a whole that is «something more than the sum» of its initial components.

Thus, two or more people develop «associated actions» as a result of their ability to do so:

- Create synergy — in other words, to develop a plan that pursues the best interests of all the parts involved.

- Respect a dialogue code, to connect the parts emotionally and cognitively, in order to share feedback and combine strengths.

- Remain as much as possible on an equal level. The more the parts interact on the same level of status, the more fruitful and generous of «third effects» their relationship will be. This process recalls the concept of reciprocity, and for this reason these two terms (relationship and reciprocity) will be used as synonymous in the next pages.

- Respect the empowerment code. The more the parts exchange each other’s their individual powers, the more a «shared power» can emerge. If one part oppresses or dominates the other, the degree of relatedness decreases and can drop to almost zero. In such cases, the relationship loses its generative power. It becomes destructive. The «power of both» (that is, the «relational power») disappears.

When these conditions are respected, mutual contributions are reinforced, with a multiplier effect.

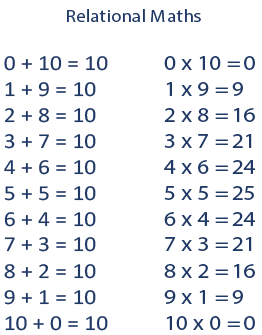

Using a mathematical metaphor, a sum is not a good representation of a relationship. It rather represents a simple pile or juxtaposition. A relationship is better represented by multiplication. Multiplication creates larger quantities (or, if the multiplier is zero, destroys them). In Figure 2, a scheme called «relational maths» is proposed. It shows that if two numbers are put together using addition — for example, 10 and 0, or 5 and 5 — the result is always 10. If the same numbers are put together using multiplication, the result will be very different. And, crucially, the closer (i.e., «on an equal level») the values of the factors are, the larger the product is.

Figure 2 Relational Maths.

Some epistemological issues

In order to understand the relational nature of Social Work, we need to make a brief epistemological reasoning. Because of its deeply humanistic and existential nature, Social Work is particularly sensitive to the ways in which it can present itself as a mature scientific discipline. Social Work researchers are constantly confronted with critical issues in this regard.

In next sections, we would like to point out two relevant questions.

Is Social Work essentially an ethical discipline and profession?

According to the Global Definition (IFSW, 2014) social work aims to alleviate suffering and promote social change for a better society. So, its general purpose is to seek the good — a good we can call «welfare» or «wellness» or «wellbeing». Since social work is concerned with «the good and the bad» — or, rather, with a good that should come out of the bad — it can be seen as an applied ethics, that need an ongoing «ethics work» (Banks, 2016).

Of course, defining what is good or bad is problematic, and it would be dangerous to base this definition solely on the convictions of social workers or on the values of Social Work as a discipline. A similar arrogant conception would be an anti-relational ethics, and therefore potentially immoral.

Fortunately, we can find a sort of solution to this problem in the pragmatic nature of Social Work. Social workers are expected to improve severe existential conditions, so the desirable «good» of Social Work could be better described in a «negative» way, as overcoming suffering. Social workers are not expected to increase or extend existing levels of social justice. Rather, they are expected to reduce unacceptable levels of injustice (Parton, 2002). They are not expected to increase existing levels happiness and well-being of Western society. Rather, they must reduce unacceptable levels of discomfort, hardship, suffering, pain, or severe distress.

This pragmatic perspective provides social workers with powerful external support in maintaining a proper moral balance. The «good» they must restore is mainly self-evident and immediately clear. Most welfare interventions are urgent and indispensable. Usually few of them «crosses the line» of a quite common conception of good. Most service users — the target of social workers — ask for help and agree with the helpers. So, they are not literally «targets»! They are «interlocutors» in a real helping relationship. On the other hand, in the case of compulsory interventions, the guidelines of the law can give some help to professionals to control their possible excessive manipulation (Rooney, 2018).

This moral (relational) standpoint of Social Work pursues a «democratic» good that is sought and enjoyed together by different individuals who are «related». As a discipline, Social Work studies an Ego sensitive to the good of Alter, and an Alter sensitive to the good of Ego. Sometimes the Ego is a service user, or a citizen, sometimes the Ego is the social worker: everyone is in an equal position in their relationship. Therefore, we can say that Social Work bases its professional intervention on the respect of the «Golden Rule» of universal ethics: Do to others as you would have them do to you. A deep respect for the value and dignity of human suffering provides an emotional and rational energy to nurture any social work helping practice.

This leads to carefully consider the following point.

Are social relations the cause of social problems, or the power to solve them?

The main epistemological topic in which we are interested here is that of determinism versus phenomenology, that is: the ideal battle of a biblical «giant with clay feet» versus an ephemeral science of the human being. This dilemma can be expressed in the question: Are social relations the cause of social problems, or the power to solve them?

The social sciences are still ambivalent about the classical question of determinism. More than a hundred years have passed since Husserl’s famous «anathema» against scientific psychology.3 Unfortunately, his enlightening idea is still not well understood. No wonder, then, that in the minds of many social workers — and sometimes in the unconscious minds of human scientists — it is still easy to find this intuitive idea: that identifying the causes of problems is the crucial step in solving them. Determinism focuses mainly on the dynamics of the past, on reasons that explain why certain things happened. Once you understand exactly how problems arose, they would be already solved!

A common idea among social workers is that relationships are the main cause of life problems. Relationships are seen as a kind of cornerstones, or foundations of human well-being, which unfortunately can easily collapse. It is from these collapses that suffering, or deviance arises, which social workers are then expected to address. Consequently, deterministic welfare scholars and practitioners take it for granted that to restore wellbeing it is necessary to intervene «on» relationships. In psychotherapy, Milan Family Systems Therapy (Selvini Palazzoli et al., 1978) seemed to support this assumption.

It is difficult to deny that many well-known social problems have deterministic origins. In child protection, for example, most of the dramatic risks or harms are associated with (or caused by) serious dysfunctions in family relationships. More generally, it is impossible to deny that social relationships often become pathological systems that produce all kinds of psychological and behavioral disorders: oppression, violence, neglect, abuse — forces that destroy the «well-being» of local communities.

Despite this evidence, social workers don’t work by looking in the rear-view mirror. Their work is mainly forward looking, open to the future. They can rarely intervene in pre-defined problems by introducing pre-defined «therapies».

The deterministic perspective is only partially acceptable in social work, for two main reasons:

- The model of linear causality is not suitable for explaining any phenomenon. Following Heisenberg’s work (Lindley, 2007), even in «quantum physics» a cast-iron determinism is no longer tenable. Should we maintain it in Social Work?

- When people come together, they can express a creative subjectivity that is potentially stronger than the many harms accumulated from their past. Their capacity to respond and their unpredictable agency can be stronger than any internal constraints (habits, compulsions, personality traits, mental addictions, etc.) or any external constraints (social, economic, cultural, institutional, etc.).

Social relations are ambivalent. If they are debilitating in one sense, they can be energising in the other. For social workers, relationships are not just «broken things» that «break other things» — in a kind of domino effect. Relations can be destructive, but they can also generate impressive contrasting psychic powers. Without these powers, Social Work would be unarmed. It should be dismissed at once. No determinism could guarantee its beneficial outcome. Unexpectedly, social relationships that have been damaged by life, can turn out to restore trust and hope. And trust and hope are the basis on which desired change can happen (Fukuyama, 1995). Social problems can be addressed in a purposeful, potential free and reflexive way.

These basic suggestions lead us to the open horizons of phenomenology. Husserl ([1959] 1970), Heidegger ([1927] 1996), Lévinas ([1930] 1970), and other great philosophers, are the masters of this powerful way of thinking. Especially in Social work, phenomenology offers a profound paradigm shift. It is a paradigm that emphasises intentionality and willpower, the human forces that can be stronger (more effective) than any technicality in restoring life.

Some professional issues

In summary, social work does not work on objects or on connections between objects. Social Work studies how to help people who want to cope with a worry, or a concern, and who seek connections and agreements with others to solve problems and improve their lives together. The epistemic «objects» of Social Work are subjects, conscious human beings with their own agency, masters of their own lives. There are many circumstances that can complicate or disrupt a person’s life, but it is precisely the management of these circumstances that is the essence of life. As Goethe wrote, «life belongs to the living, and he who lives must be prepared for change» ([1821] 2019).

From this phenomenological paradigm emerges a myriad of considerations that have significant implications for professional Social Work practice, and, by extension, for Social Work research. Let’s try to summarise them here on a hypothetical scale. It shows eight levels of relationality in Social Work professional functions and practices. Social Work practices with lower structural levels of relationality will be focused on first, followed by those with higher levels.

First reciprocity level: Top-down service provisions delivery and mandatory interventions (Bureaucratic style)

Many social workers have to deliver «standard provision» or to implement interventions under a judicial mandate. When these professional functions are carried out by prioritizing the procedures and bureaucratic requirements of regulations and laws, they often result one-sided, top-down, standardised, and impersonal (Evans & Harris, 2004; Hoybye-Mortensen, 2015; Ponnert & Svensson, 2015/2016; Nothdurfter & Hermans, 2018). Not surprisingly, many prejudices and stigmas against social workers as «welfare state» bureaucrats relate to this common-sense view (Galilee, 2005; Staniforth, Fouché, & Beddoe, 2014; Kagan, 2016).

But can we say that this style of bureaucratic help is still, to some extent, relational? The answer is yes, provided that:

- The overall effectiveness and «good outcomes» of services also depend on their impact on user’s capabilities and, more generally, on user’s life.

- The assessment process considers, as far as possible, what users and their families want and are willing to accept.

- Monitoring and evaluation practices are prepared to include, on an equal footing, the feedback and views of users and their families.

Second reciprocity level: Managerial networking, teamwork and groupwork (Engineering style)

In many contexts, social workers act as case managers. Since the liberal reforms of the Nineties, case managers have been assembling and coordinating individualized care packages, paying particular attention to the real sustainability and efficiency of the welfare spending (Payne, 1995; Clarke, Gewirtz, & McLaughlin, 2001; Hutchinson, 2013; Healy, 2022). A similar linking role is played by social workers who coordinate multi-professional teams (Martin, 2013) or lead group-work processes (Garvin, Gutiérrez, & Galinsky, 2017).

These functions appear to be relational (or «networking-oriented») because of their explicit aim: to connect separate parts so that they result in a whole or integrated overarching unit. Of course, this top-down networking — this work aimed at synchronizing «mechanisms» with an engineering style — is a valuable connectional enterprise. But is it «relational» or «reciprocal»? Yes and no. Only partly.

No, if the social worker tends to connect other people to each other only according to his/her own plans, without really relating him/herself to them. Yes, if social workers, on the contrary, remember that they are not just… an engineer, and therefore they conceive their coordination action as a function to be developed including the views of people involved (citizens and/or other professionals).

Third reciprocity level: In-depth interview with individual service users (Clinical style)

In many professional settings, social workers provide emotional support and guidance in a one-to-one helping relationship. For example, in counselling (Hill, Ford, & Meadows, 1990) or in motivational interviewing (Miller & Rollnick, 2013; Forrester, Wilkins, & Whittaker, 2021), social workers typically address the person’s inner confusion or distress. Through active and sensitive listening, they help people explore their concerns and find their own ways of coping.

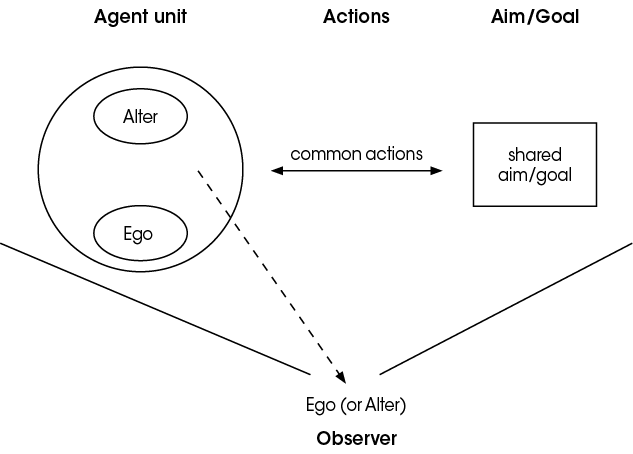

Counselling practice can be «relational» to a significant extent because two reasons. First: because in one-to-one counselling, social workers act as pure experts in «otherness». They respect and «get in touch» with the person’s independence, rationality, and wisdom, as they struggle with suffering, confusion, and irrationality. Second: because any well-trained counsellor should be able to create a «triadic» situation, that is: the minimum basis for the construction of a real «social network». This counsellor is able not only to connect with his individual interlocutor, but also to assume a detached role of observer of the dyadic relationship itself, including himself (as showed in Figure 3).

On the other hand, as counsellors, social workers can inadvertently lose a deep relational logic. They run the risk of assume a «clinical» logic of reasoning (and helping) and they can forget that any inner suffering is not only affected by the social environment, especially family and friends. It also influences them.

Here we use «clinical» as opposed to «social» and «relational». Indeed, if one reads the definitions that include the term «clinical» in the APA Dictionary of Psychology (https://dictionary.apa.org/, last accessed August 2023), it is easy to see that (a) the term refers to processes that primarily concern an individual person — regardless of whether or not «social factors» are also considered: they are in any case understood as variables that are relevant to a specific individual; (b) these processes presuppose that the responsibility for assessment, diagnosis and determination of treatment lies with the professional. This is the level at which many of the studies that speak about «relational social work» or «relationship-based practice» can predominantly be placed (for example: Ruch, Turney, & Ward, 2018; Hennessey, 2011; Megele, 2015; Bryan, Hingley-Jones, & Ruch, 2016). In these studies, the focus is the relationship between social workers and the person, a relationship understood as the main vehicle for change (Tosone, 2004).

Figure 3 The relation observed by only one of the primary agents.

Fourth reciprocity level: Relational guidance of focused coping networks (Alpine guide style)

A social worker can often intercept different sets of previously associated people who are coping together with a common worry or life crisis (Folgheraiter, 1998, 2007, 2011; for some references in the field of psychology, see Lyons et al. 1998; Mickelson et al., 2001; Basinger, 2018; Afifi, Basinger, & Kam, 2020).

All the people involved in this «coping network» (including the social worker) are motivated to find a solution or an acceptable recovery, but they have doubts about how to do it. Social workers guide people in their own planning and action to develop a concrete and well-focused «solution», i.e., solving a personal problem of one of them; changing lifestyle; reducing life or caring stress; reducing local community difficulties, etc. On their own, the people involved in the coping network offer each other and their professional guide their reflexive skills and experiential knowledge (Borkman, 1976, 1990; Cotterell & Morris, 2011; Beresford, 2010; Beresford & Boxall, 2013; Munn-Giddings & Borkman, 2017; Folgheraiter & Raineri, 2017).

This relational helping process can concern three classic social work situations: a) sometimes the helping process takes place in a casework setting, where the coping network includes not only the user but also, for example, some family members, some friends, the family doctor, the neighbour, some other professionals, etc. (Calcaterra, 2017); b) sometimes it can be a mutual support group setting (Raineri, 2017), where the coping network includes «peers» who are seeking the same recovery; c) sometimes it can be a broader community work situation, where the coping network includes citizens of the same neighbourhood who are engaged in addressing a common concern (Panciroli, 2017; Landi, 2017).

All these professional functions are relational at their core, because the two parties involved (the social worker and the network of interested people) remain on the same level of status and are relatively free to search for their recovery solutions.

The relational guidance of focused coping networks is here labelled as «Alpine guide style» because the network’s path towards better life situations can be compared to an explorative adventurous journey, in which one has to take decisions moment by moment, risking making mistakes and having to correct them (Folgheraiter, 1998). Like the local guides who, over a century ago, accompanied mountaineers on their first ascents of Alpine peaks, at the outset relational guides do not know exactly what path the network is going to develop with their help, nor even what the exact destination will be. It is an open and uncertain social intervention, both in process and outcome. This uncertainty is laborious, but also indispensable to take people’s agency deeply into account.

Fifth reciprocity level: Relational facilitation of open dialogical networks (Community co-planning style)

In many circumstances, social workers can promote the possibility of being helped by users and citizens to better understand what they must to do as social workers. In other words, professionals promote opportunities for co-planning and co-producing open projects and initiatives to prevent undefined social problems, to make better decisions about uncertain «early interventions» in community work projects and, more generally, to reflectively improve the current state of «good enough» community wellbeing (Panciroli & Bergami, 2019; Calcaterra, 2022; SCIE, 2015).

Perhaps paradoxically, social workers became here more professional by sharing their decision-making power. Structurally, the aim of this seemingly counter-professional function is not to «give answers» to people, but to gather suggestions from them. In this way, social workers can be helped to be more innovative as professional problem solvers and to grow as experts.

So, relational social workers are effective not only in the «art of helping» but also in the «art of being helped». That is: the art of enabling so-called «frail» people to become helpers themselves, giving them unexpected opportunities to «help the helpers». These opportunities for helping other people and communities are particularly valuable and therapeutic for service users (Fillingham, Smith & Sealey, 2023) who may have been oppressed and humiliated, treated as «socially useless» — to use the words of Pope Francis.

Sixth reciprocity level: Relational networking addressed to top levels of management and local policy making (Democratic participatory style)

Social workers are highly relational when they can use their voice to report back to policy makers what they have learned from their fieldwork experiences, acting from an «advocacy» perspective. Social workers can be even more relational when they can act from a «self-advocacy» perspective to facilitate direct relationships between the more abstract (sometimes abstruse) skills of managers or policy makers and the intuitive knowledge of active citizens, service users and carers, natural helpers, volunteers (Dalrymple & Boylan, 2013; Calcaterra, 2014; Scourfield, 2021). For example, they can help to open up Technical Committees of public services to so called «Experts by Experience», so that they have more of a voice and feel that they are being listened to respectfully.

Here the social worker is aware that any effective «local service planning» needs social input and feedback from service users as well as concerned, sensitive citizens. More generally, such networking practices could promote a closer relationship between civil society and welfare systems, in an authentic «welfare society» perspective (Donati, 2015).

Seventh reciprocity level: Relational network aimed at humanising care activities (Suffering honouring style)

Suffering people can help social workers to learn more about the value and nature of human life, the very human life that is ultimately the «object» of their work. Suffering people can inadvertently be great masters of humanity. They can help helping professionals to respect and honour the inevitable frailty and vulnerability of the humana conditio (to use the famous title by Norbert Elias, 1985).

Unfortunately, social workers can sometimes unconsciously help people solve their life problems with a subtle pietistic attitude or a kind of hidden contempt. The implicit idea could be that: illness is less than health; old age is less than youth; homeless people are less than homeowners; my users are less than me, because, for the moment, I am a confident and efficient professional.

Thanks to the attitude of treating frail people as equals — listening and learning about their dignity — social workers can daily enjoy the wonderful gift of understanding the deep meaning and value of their own lives. Or, at the very least, they can protect themselves from the burnout and other embarrassing psychological pain that we unfortunately sometimes see in those who work in social services.

Eighth level of reciprocity: Relational networking aimed at humanising Society (Anthropological style)

Social workers develop this broader level of relationality when they make available to society the gifts of humanity they have received in their professional practice.

Social workers can unconsciously share their knowledge about the value of human life through their direct witness. Or better still, they can do this intentionally, being supported in this witness by interested people. They can set up initiatives to promote the voice of service users (the «experts by experience») in order to reach out to those who are not directly involved in any kind of life suffering.

Why would a social worker want to do this (i.e., to support the «social» in helping the society to change)? A first reason is well known. As sensitivity to those who suffer grows, a more welcoming, caring environment develops, just as in the first idea of «community care» policies (Bulmer, 1987). We are talking about a people-centred environment in which the daily task of coping with life’s problems becomes less difficult for everyone. A second reason is deeper, in an anthropological sense. There are many people who live far from the most extreme situations of suffering and who have no idea that fate can be so hard. On the one hand, of course, they are fortunate not to be aware of the suffering. This means that they are living happily. But on the other hand, awareness of suffering could be very precious because it could lead us to see our lives in a different way, less conditioned by consumerism, triviality, and narcissism.

Social workers are often blamed because their caring activities seem to fix the structural problems of our unequal society, perpetuating injustice and oppression, and many of them seem to believe that there is no room for activism to contribute to changing society (Healy, 2001). But transforming/humanising society is a crucial task of social work. By spreading the delicate awareness of our inevitable suffering as human beings, social workers could carry out the soft revolutionary «political practice» that they ultimately have to promote.

References

Adams, R., Dominelli, L., & Payne, M. (2009). Towards a critical understanding of social work. Social work: Themes, issues and critical debates, 3rd edn. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Afifi, T. D., Basinger, E. D., & Kam, J. A. (2020). The extended theoretical model of communal coping: Understanding the properties and functionality of communal coping. Journal of Communication, 70(3), 424-446.

Banks, S. (2016). Everyday ethics in professional life: Social work as ethics work. Ethics and social welfare, 10(1), 35-52.

Basinger, E. D. (2018). Explicating the appraisal dimension of the communal coping model. Health communication, 33(6), 690-699.

Beresford, P. (2010). Re-examining relationships between experience, knowledge, ideas and research: A key role for recipients of state welfare and their movements. Social Work & Society, 8(1), 6-21.

Beresford, P., & Boxall, K. (2013). Where do service users’ knowledges sit in relation to professional and academic understandings of knowledge? In P. Staddon (Ed.), Mental health service users in research (pp. 69-86). Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

Biestek, F. (1957). The casework relationship. Chicago: Loyola University Press.

Borkman, T. (1976). Experiential knowledge: A new concept for the analysis of self-help groups. Social Service Review, 50(3), 445-456.

Borkman, T. J. (1990). Experiential, professional, and lay frames of reference. In T. J. Powell (Ed.), Working with self-help (pp. 3-30). Washington: National Association of Social Work.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bryan, A., Hingley-Jones, H., & Ruch, G. (2016). Relationship-based practice revisited. Journal of Social Work Practice, 30(3), 229-233.

Bulmer, M. (1987). The Social Basis of Community Care. London: Allen and Unwin.

Butrym, Z. (1976). The Nature of Social Work. London: Macmillan.

Cabiati, E. (2017). Social work education: The relational way. Relational Social Work, 1(1), 61-79.

Calcaterra, V. (2014). Il portavoce del minore: Manuale operativo per l’advocacy professionale. Trento: Erickson.

Calcaterra, V. (2017). Relational Social Work at the case level. Working with coping networks to cope micro-social problems. Relational Social Work, 1, 39-60.

Calcaterra, V. (2022). The community advocates: Promoting young people’s participation in community work projects. Relational Social Work, 6(2), 58-70.

Clarke, J., Gewirtz, S., & McLaughlin, E. (2001). New Managerialism: New Welfare? London: Open University Press/Sage.

Corradini, F., Landi, C., & Limongelli, P. (2020). Becoming a relational social worker. Group learning in social work education: Considerations from Unconventional Practice Placements. Relational Social Work, 4(1), 15-29.

Cotterell, P., & Morris, C. (2011). The capacity, impact and challenge of service users’ experiential knowledge. In M. Barnes & P. Cottarell (Eds.), Critical perspectives on user involvement. Bristol, UK: Policy Press. Available online DOI: https://doi.org/10.51952/9781847429483.ch005.

Dalrymple, J., & Boylan, J. (2013). Effective advocacy in social work. London: Sage.

Domenach, J. M. et al. (1972). Le travail social c’est le corps social en travail. Esprit, 413, 4-5.

Donati, P. (2013). Sociologia della relazione, Bologna: il Mulino.

Donati, P. (2015). Beyond the welfare state: Trajectories towards the relational state. In G. Bertin & S. Campostrini (Eds.), Equiwelfare and Social Innovation: An European Perspective (pp. 13-49). Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Donati, P. (2019). Discovering the relational goods: Their nature, genesis and effects. International Review of Sociology, 29(2), 238-259.

Donzelot, J. (1988). The promotion of the Social. Economy and Society, 17(3), 395-427.

Elias, N. (1985). Humana conditio. Betrachtungen zur Entwicklung der Menschheit am 40. Jahrestag eines Kriegsendes. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Evans, T. & Harris, J. (2004). Street-Level Bureaucracy, Social Work and the (Exaggerated) Death of Discretion. British Journal of Social Work, 34(6), 871-895.

Ferard, M. L. & Hunnybun, N. (1962). The Caseworker’s Use of Relationship. London: Tavistock.

Fillingham, J., Smith, J., & Sealey, C. (2023). Reflections on making co-production work: The reality of co-production from an insider perspective. The British Journal of Social Work, 53(3), 1593-1601.

Folgheraiter, F. (1998). Teoria e metodologia del servizio sociale: la prospettiva di rete. Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Folgheraiter, F. (2004). Relational social work: Toward networking and societal practices. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Folgheraiter, F. (2007). Relational social work: Principles and practices. Social Policy and Society, 6(2), 265-274.

Folgheraiter, F. (2011). Fondamenti di metodologia relazionale. Trento: Erickson.

Folgheraiter, F. (2012). The mystery of social work: A critical analysis of the global definition and new suggestions according to the relational theory. Trento: Erickson.

Folgheraiter, F., & Raineri, M. L. (2017). The principles and key ideas of Relational Social Work. Relational Social Work, 1(1), 12-18.

Folgheraiter, F., & Raineri, M. L. (2019). The relational social work: Principles and methods. In E. Carrà & P. Terenzi (Eds.), The relational gaze on a changing society (pp. 231-246). Berlin: Peter Lang.

Forrester, D., Wilkins, D., & Whittaker, C. (2021). Motivational interviewing for working with children and families: A practical guide for early intervention and child protection. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity, New York: The Free Press.

Galilee, J. (2005). Literature review on media representations of social work and social workers. Edinburgh: Scottish Executive.

Garvin, C. D., Gutiérrez, L. M., & Galinsky, M. J. (Eds.). (2017). Handbook of social work with groups. New York: Guilford Publications.

Gitterman, A., & Germain, C. B. (2008). The life model of social work practice: Advances in theory and practice. Columbia: University Press.

Hamilton, (1940). Theory and practice of social casework. New York: New York School of Social Work.

Hartman, A. (1978). Diagrammatic assessment of family relationships. Social casework, 59(8), 465-476.

Healy, K. (2001). Reinventing critical social work: Challenges from practice, context and postmodernism. Critical Social Work, 2(1), 1-13.

Healy K. (2022). Social Work Theories in Context: Creating Frameworks for Practice (Ch. 3). London: Bloomsbury Publ.

Heidegger, M. (1996). Being and Time. New York: State University of New York Press. English translation from Sein und Zeit. Tubingen: Max Niemeyer, 1927.

Hennessey, R. (2011). Relationship skills in social work. London: Sage.

Hill, M., Ford, J., & Meadows, F. (1990). The place of counselling in social work. Practice, 4(3), 156-172.

Hirst, P. (1981). The Genesis of the Social. Politics and Power, 3, 67-82.

Hollis, F. (1964). Casework: A psychosocial therapy. New York: Random House.

Howe, D. (1998a). Relationship-based thinking and practice in social work. Journal of Social Work Practice, 12, 45-56.

Hoybye-Mortensen, M. (2015). Decision-making tools and their influence on caseworkers’ room for discretion. British Journal of Social Work, 45(2), 600-615.

Husserl, E. (1970). The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology. Chicago: Northwestern University Press. English translation from Die Krisis der europäischen Wissenschaften und die transzendentale Phänomenologie. L’Aja: Martinus Nijhoff ’s Boekhandel, 1959.

Hutchinson, A. J. (2013). Care management. Blackwell Companion to Social Work, 4th edn., Oxford: Blackwell, 321-332.

IFSW (2014), Global Definition of Social Work. https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/ (Retrieved August 2023).

Kagan, M. (2016). Public attitudes and knowledge about social workers in Israel. Journal of Social Work, 16(3), 322-343.

Landi, C. (2017). «The future is now»: An experience of future dialogue in a community mediation intervention. Relational Social Work, 1(1), 80-89.

Lévinas, E. (1970). Théorie de l’intuition dans la phénoménologie de Husserl (1930). Paris: Jean Vrin.

Lindley, D. (2007), Uncertainty: Einstein, Heisenberg, Bohr, and the Struggle for the Soul of Science. New York: Doubleday.

Lyons, R. F., Mickelson, K. D., Sullivan, M. J. L., & Coyne, J. C. (1998). Coping as a Communal Process. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 15(5), 579-605.

Martin, R. (2013). Teamworking skills for social workers. Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press:

Megele, C. (2015). Psychosocial and relationship-based practice. Northwich: Critical Publishing.

Mickelson, K. D., Lyons, R. F., Sullivan, M. J. L., & Coyne, J. C. (2001). Yours, mine, ours: The relational context of communal coping. In B. R. Sarason & S. Duck (Eds.), Personal relationships: Implications for clinical and community psychology (pp. 181-200). Hoboken, NJ, John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change (3rd edition). New York: Guilford Press.

Munn-Giddings, C., & Borkman, T. (2017). Reciprocity in peer-led mutual aid groups in the community: Implications for social policy and social work practices. In M. Torronen, C. Munn-Giddings, & L. Tarkiainen (Eds.), Reciprocal relationships and well-being (pp. 57-76). London: Routledge.

Newman, W. L. (Eds.). (2010). Politics of Aristotle: with an introduction, two prefatory essays and notes critical and explanatory. Cambridge, UK, Cambridge University Press.

Nothdurfter, U., & Hermans, K. (2018). Meeting (or not) at the street level? A literature review on street‐level research in public management, social policy and social work. International Journal of Social Welfare, 27(3), 294-304.

O’Brien, M. (2004). What is social about social work? Social Work and Social Sciences Review, 11(2), 5-19.

O’Leary, P., Tsui, M. S., & Ruch, G. (2013). The boundaries of the social work relationship revisited: Towards a connected, inclusive and dynamic conceptualisation. British Journal of Social Work, 43(1), 135-153.

Panciroli, C. (2017). Relational Social Work at the community level. Relational Social Work, 2, 36-51.

Panciroli, C., & Bergami, P. (2019). Community social work in Child Protection: Texére project in Milan. Relational Social Work, 3(2), 51-59.

Panciroli, C., Corradini, F., & Avancini, G. (2019). The participatory research approach. Suggestions by the Relational social work method. In E. Carrà & P. Terenzi (Eds.), The relational gaze on a changing society (pp. 265-288). Berlin: Peter Lang.

Parton, N. (2002). Social theory, social change and social work: An introduction. In Social theory, social change and social work (pp. 4-18). London: Routledge.

Parton, N. (2008). Changes in the form of knowledge in social work: From the social to the informational? British Journal of Social Work, 38, 253-269.

Payne, M. (1995). Social work and community care. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Ponnert, L. & Svensson, K. (2015/2016). Standardisation: The end of professional discretion? European Journal of Social Work, 19(3-4), 586-599.

Raineri, M. L. (2017). Relational Social Work and mutual/self-help groups. Relational Social Work, 1(1), 19-38.

Rooney, R. (2018). Legal and Ethical Foundations for Work with Involuntary Clients. In R. H. Rooney & R. G. Mirick (Eds.), Strategies for Work with Involuntary Clients (pp. 19-46). New York: Columbia University Press.

Ruch, G. (2005). Relationship-based and reflective practice in contemporary childcare social work. Child and Family Social Work, 10(2), 111-123.

Ruch, G. (2009). Identifying «the critical» in a relationship-based model of reflection. European Journal of Social Work, 12(3), 349-362.

Ruch, G., Turney, D., & Ward, A. (2018) Relationship-based social work: Getting to the heart of practice (2nd ed.). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Schofield, G. (1998). Inner and outer worlds: A psychosocial framework for child and family social work. Child and Family Social Work, 3, 57-67.

SCIE (2015). Coproduction in Social Care: What it is and how to do it, www.scie.org.uk (Retrieved August 25, 2023).

Scourfield, P. (2021). Using advocacy in social work practice: A guide for students and professionals. Routledge.

Selvini Palazzoli, M., Boscolo, L., Cecchin, G., & Prata, G. (1978). Paradox and counterparadox: A new model in the therapy of the family in schizophrenic transaction. Lanham, Maryland: Jason Aronson, Incorporated.

Staniforth, B., Fouché, C., & Beddoe, L. (2014). Public perception of social work and social workers in Aotearoa New Zealand. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 26(2/3), 48-60.

St. Augustine (1949). The Confessions of Augustine. Letchworth-Herts: The Temple Press.

Steinberg, D. M. (2014). A mutual-aid model for social work with groups. London: Routledge.

Todd, D. (1979). Social Networking Mapping. In W. R. Curtis (Eds.). The Future of Use of Social Network in Mental Health. Boston: Social Matrix Inc.

Tosone, C. (2004). Relational Social Work: Honoring the Tradition. Smith College Studies in Social Work, 74(3), 475-487.

Trevithick, P. (2003). Effective relationship-based practice: A theoretical exploration. Journal of Social Work Practice, 17(2), 163-76.

von Goethe J. W. (1821-2019). Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship & Wilhelm Meister’s Journeyman Years, trad. by T. Carlyle and H. H. Boyesen, Prague: e-artnow Publ.

Winter, K. (2019). Relational social work. In M. Payne, & E. Reith Hall (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Social Work Theory (pp. 1-10). London: Routledge.

Folgheraiter, F. & Ranieri, M. L. (2023). The relational foundation of Social Work. Relational Social Work, 7(2), 2-21, doi: 10.14605/RSW722301.

Relational Social Work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License

1 About words that are clear in appearance only, St. Augustine writes: «These words we speak, and these we hear, and are understood, and understand. Most manifest and ordinary they are, and the self-same things again are but too deeply hidden, and the discovery of them were new» (St. Augustine, The Confessions, 1949, p. 268).

2 In English: The social work is the social body at work (translation by us).

3 Husserl discusses the problem of scientific psychology when drawn into the orbit of positivism. He declares «Merely fact-minded sciences make merely fact-minded people […]. In our vital need this science […] excludes in principle precisely the questions which man, given over in our unhappy times to the most portentous upheavals, finds the most burning: questions of the meaning or meaninglessness of the whole of this human existence. [...] These questions, universal and necessary for all men, demand universal reflections and answers based on rational insight. In the final analysis they concern man as a free, self-determining being in his behaviour toward the human and extrahuman surrounding world and free in regard to his capacities for rationally shaping himself and his surrounding world. What does science have to say about reason and unreason or about us men as subjects of this freedom?» (Husserl, [1959] 1970, p. 6).