Social inclusion determinants among the geriatric population in contemporary Ghana

Dan-Bright S. Dzorgbe

University of Ghana, Ghana

Delali A. Dovie

University of Ghana, Ghana

CORRESPONDENCE:

Delali A. Dovie

e-mail: dellsellad@gmail.com

Abstract

This paper reflects on the extent of social inclusivity among Ghana’s older adults. The study investigates the factors that influence the social inclusion of older adults in contemporary Ghana, using a cross sectional design and, quantitative and qualitative datasets. The findings show that three distinct factors: first the weakening of extended family system, second, formal support infrastructure, and last but not the least, witchcraft accusation(s) shape the social inclusion or otherwise of older persons. As a result, in contemporary Ghana, the rules of social inclusion and exclusion of older people find expression in the state’s social protection programs such as LEAP, NHIS, pensions which appear to be bearers of older people’s inclusion and exclusion simultaneously in the Ghanaian society. Further, social inclusion is also affected by witchcraft accusations with implications for social exclusion. Therefore, the notion of witchcraft accusation runs counter to older people’s social inclusivity in the Ghanaian society. Collectively, these have implications for care planning at large and social exclusion, intergenerational solidarity at the individual, community and national levels. In conclusion, the social inclusion of older adults from the viewpoint of the results herein presented is suggestive of expanding the frontiers of social inclusion and for that matter the care basket of logistics at all levels in the Ghanaian society with policy implications.

Keywords

Social exclusion, witchcraft accusations, social disintegration, dementia, pastors’ pronouncements, ageism.

Introduction

Globally, Since the beginning of the new millennium, aging has become a major socio-demographic issue. According to the UN Department of Economic Affairs’ (2017) estimated that the population over the age of 60+ years will reach 962 million in 2017 and 2,1 billion by 2050. The population pyramid in Iran for instance, also shows that currently a high percentage of the population is in the age group of 15-64 years which will lead to a large population of older people during the subsequent decades. Population aging is perceived as a major challenge for the countries that are seeking safety and welfare for their ever-increasing population of older people. This is because many people are living longer, yet not all live or are living well. Persons aged 60+ are affected by increased non-communicable diseases (NCDs), which are required to prevent and manage NCDs in order to enable older adults to enjoy better quality of life as well as continue to be productive societal members (WHO, 2019). For instance, preparations targeted at older people requires that social determinants of health are addressed, namely living conditions, social inclusion and social security.

In Ghana, data from the 2010 Population and Housing Census shows that although the proportion of older persons (60+ years) decreased from 7,2% in 2000 to 6,7% in 2010, in terms of absolute numbers there has been a sevenfold increase in the population of older persons from 215, 258 in 1960 to 1, 643, 978 in 2010 (National Population Council (NPC), 2014). The increasing numbers of older adults calls for discussions and dialogue on issues pertaining to older adults including social participation discussed in the next section.

Social Participation

Social participation is defined as «a person’s involvement in activities that provide interaction with others in society or the community» (Levasseur, Richard, Gauvin, & Ramond, 2010, p. 2148). Social participation is viewed as one of the important and effective factors influencing the older people’s welfare and health as well as an important issue of the older people’s rights. Social participation is highly valued in old age (Aroogh & Shahboulaghi, 2020) as well as an organized process in which individuals are characterized by specific, collective, conscious and voluntary actions. Ultimately, these lead to self-actualization and achievement of goals. As various research suggests, developing and sustaining social participation is a vital need for all ages, including older people (Moradi, Fekrazad, Mousari, & Aarshi, 2013; Richard, Gauvian, Gosselin, & Laforest, 2009; Jerliu, Burazeri, & Togi, 2014). Social participation is a very valuable concept in old age since it is considered as one of the most important components of the older people’s health, and a key component of many functional conceptual models in older people (Levasseur et al., 2010).

Several studies indicate that diseases, mortality, and quality of life of the elderly are related to their social participation. The social participation of older people is considered as one of the major areas of age-friendly cities, the central component of successful aging, a component of social capital, and one of the significant components affecting the health of older people. Thus, paying attention to the concept of social participation in older adults is of particular essence, and its promotion is one of the key recommendations of the WHO in response to concerns about the aging population.

Despite the importance of the concept of social participation, less attention has been paid to it, and few researches have been conducted in the field of aging. The insufficient evidence can be attributed to the lack of clarity of this concept, since the concept of social participation among older people has not been well developed and has not been clearly understood and measured. Use has been made of terms such as social integration and social activity as an alternative to the concept of social participation (Alexiu, Lazer, & Baciu, 2011).

Social Inclusion of Older Adults

Notions of social inclusion in social care is issues worth reiterating and discussing. According to the World Bank (2013), social inclusion is defined first as the process of improving the terms for individuals and groups to participate in society, and second, as the process of improving the ability, opportunity, and dignity of people, disadvantaged on the basis of their identity, to take part in society. Social can relate to diverse areas of social groups. These entail demographic differentiations with regard to socio-economic, status, culture and primary language (Gidley, Hampson, Wheeler, & Bereded 2010). Social inclusion also relates the process of improving the terms of participation in society, especially for people who are old through enhancing of opportunities, access to resources, voice and respect for rights (Charity Commission, 2001; Dovie, 2020). Social inclusion encompasses ability, opportunity and dignity in the interface and markets; services (e.g., social protection, information, electricity, transport, education, health, water). From the social viewpoint, exclusion is used as a synonym for poverty, marginalization, detachment, unemployment, or solitude. Social exclusion helps in understanding poverty and disadvantage (Wilde, 2018), as well as income, assets, access to health services and transport. Older adults’ exclusion is partly caused by negative attitudes and discrimination (Azpitarte, 2013; Gooding, Anderson, & NcVilly, 2017). Older adults may be excluded economically, politically, socially and culturally.

By inclusion in Ghana, Gyekye (2015) does make reference to gender, ethnic, racial or immigrant groups in a nation that are perhaps excluded from political processes by virtue of deprivation from certain political rights. He rather refers to ordinary citizens such as individuals including older adults who have civil or political rights yet have nevertheless been excluded or marginalized. This refers to ordinary citizens whose voices have been in the «wilderness». In the political practice of the nation of Ghana inclusion is more fundamental, even in relation to the problems of inclusion which have been negotiated, culminating in the recognition of the political or civil rights of these groups (albeit gender, age, ethnicity, immigrant, to mention but a few) that have been previously excluded from formal civil or political processes. Such people will demand full participation in political or state level processes including participating in decision-making that affects their lives.

Formal Care Practice(s) in Ghana

Issues of social protection border on the Ghanaian context particularly on the provision and availability of formal support infrastructure such as the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), Livelihood Empowerment Against Poverty (LEAP), pensions.

The LEAP program focuses on interventions namely cash transfers to older people, people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWAs), (Mohammed & Domfe, 2016). This is expected to be attained through social assistance to reduce poverty, promote productive inclusive income support, livelihood empowerment and improved access to basic schemes (e.g., LEAP, (Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection (MGCSP), 2015) among others. The inclusivity mandate is due to the fact that the retirement age is 60 years, yet beneficiaries of LEAP are to be aged 65+. This depicts a node of exclusion. The age barrier indicated above limit the accessibility of the few formal support infrastructure by some older adults and are therefore counter to social inclusion since they are excluding in nature.

The NHIS was introduced nationwide in 2005. It was aimed equitable and financial access to basic healthcare services. The vision of the Ghanaian government in establishing the health insurance scheme in Ghana was to assure equitable universal access for all Ghanaian residents to and acceptable quality of a package of important health services without out-of-pocket payment being required at the point service use (Ministry of Health, 2004; Abuosi, Nketiah-Amponsah, Abor & Domfeh, 2016). However, diverse views pertain as to the effectiveness of the financial protection of the intervention. As a result, some studies (e.g., Saksena et al., 2011) have shown that enrollment on the insurance scheme reduces households’ out-of-pocket spendings. Thus, improving financial access and increased utilisation of the health service. Others find that that enrollment on the health insurance scheme may lead to increased out-of-pocket spending (Abuosi et al., 2016). From a healthcare perspective, the NHIS Act (Act 650) of 2003 provides for an exemption for individuals aged 70+ years and non-contributors to the Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT). The exemption clause covers older adults aged 65+ and registered under the LEAP Cash Transfer Program from the payment of registration fees and premiums to access to health services under the NHIS (Dovie, 2019).

Formal social protection includes social security and/or pensions (Agbobli, 2011; Barrientos, 2004; Kumado & Gockel, 2003). Pension systems and the associated contributions worldwide are one of the major mechanisms for preparing towards retirement, the significance of which cannot be overemphasised. Informal social protection on the other hand entails extended family support especially from children, participation in susu and credit union(s) (Aboderin, 2004; Barrientos, 2004). In Ghana however, most previous research focus on social security (Kumado & Gockel, 2003); others dwell extensively on the three-tier pension scheme (Kpessa, 2011; Obuobi, 2019; van Dam, 2014; wo Ping, 2013) without clearly disaggregating the different strands of retirement income pillars. Functionally, the National Pension Act (2008) seeks to mobilize funds through pension contributions by the working population for various contingencies, particularly old age, invalidity, and death (Government of Ghana (GOG), 2008).

The social protection policy attempts to deliver a well-coordinated and inter-sectoral social protection system that will enable people to live their lives in dignity.

Social Care for Older People

All societies worldwide including Ghana contain individuals who are in need of care. Perhaps, all people in all societies are in need of care including normal and non-disabled adults, who constantly rely on care by others in the social fiber in different facets of their lives namely people who prepare meals, tend the home, providers of regular healthcare, people who prepare the external environment such that it is safe and conducive to ordinary functioning (Nussbaum, 2006). Even the otherwise normal or able-bodied people have more acute needs for care especially during an illness for example after an accident. Also worth noting is that the phase of self-sufficient adulthood is usually followed in turn by a period of increasing dependency, particularly as ageing succumbs to new physical and mental needs. Quintessentially, increasing life expectancy has given rise to numerous new sets of dependencies as children need to care for their aged parents in the latter’s physical and mental decline. Nussbaum (2006) notes that human beings all over the world are perhaps disabled beings who have many imperfections in judgement, understanding, perception and bodily functioning. Yet, society does not seem to be typically arranged to cater for most typical disabilities (p. 276). Other national citizens including older adults have disabilities that make dependency on others an unavoidable fact of their daily lives. For instance, people with severe mental disabilities may never be able to live on their own without the reliance on caregivers for their daily needs.

In the Ghanaian context, different dimensions of the ageing population — males or females — have somewhat different care components, for instance, (older) women are expected to care for themselves since it is believed that they are and have largely been in charge of the households even while their spouses were alive and still alive (Tonah, 2007). It is worth mentioning that women also care for others (Dovie, 2019). This is an age-old task that appears to be their preserve. For as much as the government is not forthcoming with a concrete older people care regime, informal care is targeted at attaining at same aim for older adults in Ghana. However, with time a new «mixed care» may have to be created which seeks to combine formal and informal (familial) care for older adults (Dovie & Ohemeng, 2019; Dovie 2020).

Social change has been necessitated by factors such as modernization, industrialization and urbanization, have brought a new twist and turn to the care for older people across the globe including Ghana. As a result, older adults are no longer automatically guaranteed protection, support as well as quality of life as previously used to be the case by virtue of their age and position in the family and society (Ayete-Nyampong, 2015) at large. Ayete-Nyampong (2014) opined that the reality and challenges of ageing are issues that confront Africa and Ghana in the 21st century that are impregnated with crisis if nothing is done to explore the positive perspectives of ageing in order to remedy the problem associated with it. In years past, older people’s population had not reached a significant level. Hence their welfare which largely used to be the responsibility of the extended family was not seen as a problem that demanded national and continental attention. However, presently the population of Ghana’s older people has increased from 213, 477 in 1960 to approximately 2 million (1, 991, 736) in 2021 (GSS, 2022). This requires attention as far as this population and its related needs such as inclusion socially is concerned.

Witchcraft Accusations

Witchcraft accusation is often resorted to when rational knowledge fails. It seeks to explicate diseases whose causes are not known, the mysteries surrounding death and more generally, strange and unexplainable misfortunes. Witchcraft is deeply rooted in many African states and communities in sub-Saharan Africa. It has been specifically relevant in the culture of beliefs, lifestyle of Ghanaians and continually shapes lives on daily basis (Roxburgh, 2016). It promotes tradition, fear, violence and spiritual beliefs. Witchcraft relates to encounters with attempts to control the supernatural (Moro, 2018). Viewpoints from anthropologists intimate that the term «witch» denotes someone who has been alleged to practice socially prohibited forms of magic. Notions of witchcraft and the studies related to it date back to the mid-19th century, pursued through diverse schools of thoughts.

In many nations across the world, witchcraft beliefs and practices have led to serious violations of human rights such as beatings, banishment, cutting of body parts and amputation of limbs, torture and murder. Women, children, older people and persons with disabilities especially persons with albinism, including the vulnerable. Beliefs and practices regarding witchcraft are diverse in different countries and even within ethnicities in the same nation (UN Human Rights, 2020). In many societies, there have been means for mediating the threat of witchcraft attacks, which is non-violent, though some have been abandoned whereas others may have proved to be irretrievable (Roxburgh, 2016).

A gap exists in the Ghanaian literature on knowledge relating to social inclusion and social exclusion of older adults in Ghana. It is this gap that this study sought to fill by focusing on how declining extended family support system, formal care practice(s) and witchcraft accusation shape the inclusion of older adults socially. The study sought to investigate the following research objectives: To explore the extent to which older adults are socially included in contemporary Ghana, second. To proffer some recommendations on expanding the frontiers of older adults’ social inclusion in society. The research questions on the other hand, are:

- To what extent are older adults socially included in contemporary Ghana?

- What is the way forward in expanding the frontiers of older people’s social inclusion in Ghana?

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework that guides the discussion in this paper is the structural lag theory (Riley, Kahn & Foner, 1994) and relational social work theory. The structural lag theory argues that institutions in society have lagged behind the realities of healthy and capable older population. This is the case notwithstanding breathtaking advances in medicine that have increased dramatically the active life expectancy of older persons. Social institutions, particularly the economy are still pushing out the responsible position of earlier ages. Yet, even community institutions and/or organizations need to make changes in services for older adults who have lagged behind in the needs of a rapidly ageing population, such that even in healthcare for instance, the management of care principle is continually at odds with the realities of the various older populations in relation to healthcare needs and resources. Comparatively, the structural lag theory points to potential solutions in the future. It is an extension of the stratification theory since it proposed solutions to problems of structural lag which often reside in the relations between the age strata.

Relational social work is organized around two (2) principles. First, social work practice is grounded on the belief that human behavior develops and can only be understood in the context of interpersonal relationships, social and cultural conditions. Essentially, a key feature of this is its person-in-situation perspective. Second, in exception of cognitive-behavior approach, emphasis is placed on the client-worker relationship in the therapeutic process. Relational ideas have expanded and changed over the years and have gone through different phases. Relational thinking tended to focus on how the caretaking environment nurtures and influences individuals’ development and well-being. Other relational contributions take place in mutuality and interaction in the relationship between for instance, older people and significant others (Goldstein, Miehls & Ringel, 2009).

The relational social work perspective includes both current interpersonal, environmental and cultural factors that have a bearing on older people’s problems, personality, motivations as well as strengths. This brings to the fore understanding of older people and the possible causes of their difficulties. Relation theory perceives as early stated all his/her as a product of the interaction between individuals, albeit older people and others (Goldstein et al., 2009). Incorporating this in the context of social inclusion parameters necessitates major changes in the way older people are treated from a practice viewpoint and treatment principles. Early relational theorists stressed emphatic attunement to plight of older people and elimination of countertransference attitudes that may interfere with empathy towards older people.

Methodology

This study used quantitative and qualitative methods and a cross-sectional design to investigate how formal care practices and witchcraft accusation shape the social inclusion of older adults in Ghana. Use was made of the survey and in-depth interview data to achieve this aim.

Site Selection

Accra and Ho situated in the Greater Accra and Volta regions of Ghana were chosen as the study sites. These sites provide richer and more interesting data.

Sample Selection

The study adopted the simple random sampling technique in selecting the respondents. The sampling process included the stratification of the population of regions into two (2) strata namely 0-59 and 60+. The 60+ stratum was further stratified into the following stratums: 60-69; 70-79; 80-89; and 90+. A random sample of individuals aged 60+ years (150) were each selected from the Greater Accra Metropolis and the Ho Municipality respectively. The sample for Greater Accra was selected from a total population of 4,010,054 of the Greater Accra Region (GSS, 2012) of which Accra a part, the sample of 4,010,054 were stratified. The sample for the Ho was selected from a total population of 61, 099 of the Volta Region (GSS, 2012). The sample size was calculated using the following formula: n = 2(Za+Z1–β)2σ2/Δ2, with a power of 80% and a constant of 1,65 and a p<0,05 (Kadam & Bhaleros, 2010).

A purposive sampling technique was used in selecting the 10 older adults for who participated in the survey who selected and who took part in-depth interviews. These older adults were selected based on the need for further explication of the issues explored with the survey instrument.

For the purpose of the study and to respond appropriately to the research objectives, only older adult members aged 60 and above were included in the study. Below is the socio-demographic information of the 10 in-depth interview participants (Table 1).

|

Respondent |

Pseudonym |

Gender |

Age |

Marital Status |

Education |

Occupation |

|

R1 |

Adzoba |

Female |

69 |

Widow |

Standard 7 |

Retired |

|

R2 |

Badu |

Male |

89 |

Widower |

PhD |

Retired |

|

R3 |

Falila |

Female |

67 |

Married |

GCE O’Level |

Retired |

|

R4 |

Kobla |

Male |

65 |

Married |

PhD |

Senior lecturer |

|

R5 |

Lena |

Female |

65 |

Married |

Masters’ |

Retired |

|

R6 |

Morley |

Female |

66 |

Separated |

Bachelor’ degree |

Trader |

|

R7 |

Niko |

Male |

60 |

Married |

Masters’ |

Clergy |

|

R8 |

Norman |

Male |

64 |

Married |

PhD |

Retired |

|

R9 |

Nuworzamedo |

Male |

90 |

Widower |

PhD |

Retired |

|

R10 |

Obenewaa |

Female |

77 |

Married |

Masters’ |

Businesswoman |

Table 1 Participants’ demographics (source: Field data).

Data Collection Instruments

Following Jenn’s (2006) guidelines for questionnaire development, a theoretical framework was developed including a clear set of research questions. Questions that were valid and reliable were then designed. The developed questions are «close-ended» or «open-ended» in nature, with the former more than the latter. The closed ended questions entailed the following:

Do you feel included in the Ghanaian society as an older person?

a. yes [ ] b. no [ ] c. don’t know [ ]

Older people are socially included in the Ghanaian society.

a. agree [ ] b. strongly agree [ ] c. neutral [ ] d. disagree [ ] e. strongly disagree [ ]

The open-ended questions included the following:

What form should social inclusion of the elderly take in Ghana?

What are your views about ageing and old age in Ghana?

For instance, Hershey and Mowen’s (2000) verbalised scale from «strongly agree» to «strongly disagree» was used. The options available for each closed-ended set of questions were as exhaustive as possible. The questions were ordered logically, starting with simple questions before moving to more complex questions. This was undertaken by commencing with the socio-demographic information of the respondents.

A «translate-back-translate» method was adopted in translating the questionnaire and in-depth interview guide. Two (2) translators each were engaged to translate the questionnaire and interview guide from English to Twi and Ewe respectively, which are the predominant local languages spoken in the Greater Accra and Ho in Ghana. And another set of two (2) independent persons, who were unaware of the English questionnaire, back-translated the Twi and Ewe questionnaire and in-depth interview guide to English again. Finally, the title of the questionnaire and interview guide, which reflected the main objective of the research was highlighted. The questionnaire was divided into three (3) sections according to the content, with each section flowing smoothly from one section to another. The following are the sections: Section A: socio-demographic characteristics such as demographic characteristics such as age, gender, level of education, the lived experiences of social inclusion of older adults; Section B: Social inclusion and participation; Section C: Challenges to social inclusion and participation and the way forward. After developing the questionnaire, colleagues and friends were asked to comment on the questionnaire. Mistakes in terms of content, grammar and format were picked up. This was followed by asking the potential respondents to answer the questionnaire and provide their feedback. This has been discussed below in the paragraph on pilot testing of questionnaire. The administration of the questionnaire lasted for 45 minutes whereas the in-depth interview guide lasted for 35 minutes. Some of the questions contained in the in-depth interview guide includes: Please tell me about yourself; What form should social inclusion of the elderly take in Ghana? What needs to be done make Ghana an old age inclusive society? Reliability and validity in the study were ensured by pretesting the questionnaire and interview guide as recommended by (Blumberg, Cooper, & Schindler, 2014).

To ensure reliability of the instrument, it was pretested on a sample of thirty individuals, following the guidelines proposed by Perneger, Courvoisier, Hudelson and Gayet-Ageron (2015). The questionnaire was pilot tested on 30 respondents at which 90 % confidence interval was reached in terms of 0,10 for a sample of 30 participants. Similarly, the interview guide was piloted on two (2) older persons. Confusing or sensitive questions were asked the respondents to comment specifically during the pilot test.

Together, these were collectively contextualized to fit this study and the Ghanaian scenario. The survey questionnaire instrument’s reliability was ensured in diverse ways, namely, through facilitation by clear instructions and wording of questions. The questionnaire contained standardized instructions, namely «please tick where appropriate». Also, trait sources of error were minimized through interviewing respondents at their convenience. The validity of the survey data was attained following Nardi’s (2006) guidelines. The validity of the data was obtained by means of face-to-face interviews. The face-to-face interviews were conducted in both the English language and Ghanaian languages, namely English, Ewe, and Twi.

Data Collection Procedures

For the quantitative data collection dimension, a questionnaire with closed ended questions was used as the tool for data collection. Therefore, 300 questionnaires were given out and were returned for the quantitative component of the data. The sample is large enough to help address the research questions accurately. An interview guide was used for the collection of the qualitative data. Ten older adults were selected and contacted for the in-depth interview. As earlier stated, the it took 45 and 35 minutes respectively to administer both the questionnaire and interviews. An interview guide was used for the collection of the qualitative data. Detailed explanation on the purpose of the study was given to the participants to ensure that they understand what the research was about. After completing the data collection, the recorded interviews were transcribed. The in-depth interviews were conducted in English, Ewe and Twi languages, and were audio-taped and transcribed.

Ethical Consideration

Verbal informed consent was obtained from each research participant during the process of data collection. The verbal consent was sought from the participants prior to the collection of the data. The benefits including the duration of the study was clearly spelt out to them verbally. Information on the requirements of the study were well explained to the participants before they participated in the study. The participants took part in study voluntarily and the questionnaires were administered on individual basis, in a relaxed and conducive atmosphere.

Data Analysis

The answered questionnaires were cleaned and serialized for easy identification. A data entry template for the quantitative data was developed in Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS). Quality checks were executed to ensure that the questionnaires were answered as expected before being entered for analysis into using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 20.0). The survey data were then entered into SPSS and were analyzed with selected descriptive statistics, namely frequencies and percentages were used to analyzed and express the general idea of trends in the data and to show the occurrence of different observations as investigated in the study. The in-depth interview data was analysed using thematic analysis procedures.

The findings from quantitative and qualitative analysis were triangulated to provide a holistic account of the phenomenon under study. As mentioned earlier, the qualitive interviews were conducted in both local languages and English language. The transcripts were translated into English language for easy use and understanding. These generated transcripts that were validated by a language expert and afterwards by the study participants for validation. Braun and Clark’s (2006) thematic analysis steps were used to analyse the qualitative data: first the researcher became familiar with the data through reading, second codes were generated, third themes were generated, fourth the themes were reviewed, fifth, there was the defining and naming of themes, and finally, exemplars were located. The transcripts were exported to NVivo for coding and therefore analysis. The transcripts were previewed and the coding framework determined. The data were coded, in the process of which there was the determination of patterns and interconnectedness of narratives, deduction of subthemes and themes were done.

Results

Overview of Findings

The results presented in this section were obtained from both quantitative and qualitative data. The topics discussed in this section entailed the following: factors that influence older people’s social inclusion; inadequacies of formal support; the challenges encountered by older persons at the behest of social inclusion and recommendations for surmounting them.

From the findings, the sample for the study consisted of 150 males (50%) and 150 females (50%) aged 60+. The highest educational level attained by a near majority of the respondents (64,7%) was tertiary level of education. (Table 2).

|

Variables |

Characteristics |

Frequency |

Percent (%) |

|

Age |

60-69 70-79 80+ |

100 100 100 |

33,3 33,3 33,3 |

|

Sex |

Male Female |

150 150 |

50 50 |

|

Educational level |

No formal education Pre-tertiary education Tertiary |

44 62 194 |

14,6 20,7 64,7 |

|

Marital status |

Married Separated Divorced Co-habiting Single Widowed |

127 49 39 27 30 38 |

42,3 16,3 9,7 9 10 12,7 |

Table 2 Respondents’ Demographics (source: Field data).

Factors that Influence the Social Inclusion of Older Adults

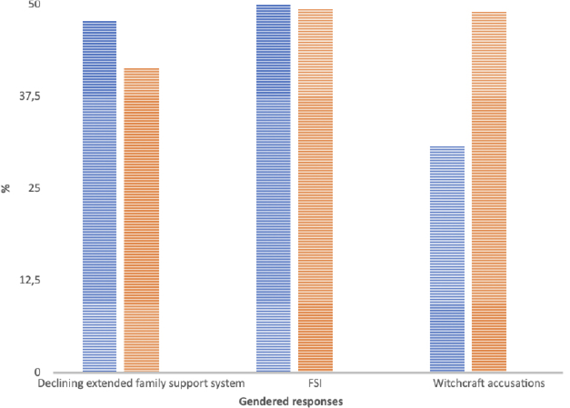

In outlining the factors that influence the social inclusion of older adults socially, the survey data shows that more male respondents (50%) mentioned formal care practice(s) as a factor. Noteworthy is that these responses can be ranked percentage wise and by that, the male respondents’ responses can be indicated in the following way: FCPs, declining extended family support system and witchcraft accusations. In the case of the females on the other hand, the order is: FCPs, witchcraft accusations and declining extended family support system (49%). From the foregoing views, FCPs appears to be the most influencing factor for both genders, and particularly for the men, whereas for the women, it is witchcraft accusations. This is not surprising as more women are subjected to the phenomenon compared to their male counterparts (figure 1).

Fig. 1 Factors Influencing Social Inclusion (source: Field data).

Inadequacies of Formal Support

The findings from the quantitative data show that majority of the older adults (50,3%) intimated that they feel they are included in the Ghanaian society as older persons (figure 1). They offered the following reasons. For example, social inclusion can occur at the national or state level, societal and community levels and individual level. The interview data shows Niko was included at the local community level.

I feel included at the local community level since some opinion leaders and the youth in his community often seek my advice and guidance in decision making but I feel left out in terms of national policies.

The statement above speaks to the key issue of the participation of older adults in policy formulation and enactment.

According to 17% of the older adults, they are not included in the Ghanaian society (Figure 1). The findings show that older adults in Ghana are largely excluded from a variety of activities at the state level namely policy decision making, advisory role performance. This includes failure to tap into their rich experience and expertise. First, Norman’s quote articulates three (3) dimensional viewpoints of social inclusion namely participation in state policy deliberations/decision-making, advisory role, performance including tapping into the rich experiences and expertise of older people.

Older people or the aged, on a large extend are excluded when it comes to state policies in terms of their general welfare but when it comes to decision making and advice, society tend to tap into their rich experience and expertise.

Second, social inclusion means different things to different people. For instance, in one case, social inclusion is reflective of being paid a pension and working even in the government or formal sector.

The older people are excluded because they are not paid well. Because government does not care about me anymore, I can’t work in the government sector to get full payment and now that I’m old I feel the country is for the youth and I’m not part (Badu).

Third, Adzoba argues that state policies are not rigorously aging and older people driven and are implemented haphazardly. For example, Ghana’s pension system is weak such that it cannot adequately meet the needs of older people even to the barest minimum.

Significantly, I can see that many of government policies and programs do not take into consideration older people and ageing. Our pension system is very weak and some of the existing policies are not being implemented as it supposed to be (Adzoba).

Fourth, Norman and Nuworzamedo intimated that from the perspective pf social inclusion, older people are not given a fair treatment when it comes to the formulation of and/or enactment of state policies and programme. This implies that older people still feel they worth their salt and must be given the opportunity to prove it through the process of social participation and therefore being socially included in such affairs.

Accommodation for the elderly should be looked at: improved health care; We should be included in the policies and decisions making; We should be appreciated. Our leaders who always travel outside should not only go and enjoy the foreign facilities but they should learn from them; their policies and programs for older people and aging. The youth also have to speak up as early as possible because they will one day be in our shoes (Norman).

Not at all! When it comes to government policies and program it is very bad, compared to abroad […] (Nuworzamedoo).

Fifth, the voice of Niko below brings to the fore social care challenges that older Ghanaian people are exposed to. This is particularly due to declining extended family support system. Hence, the shrinkage of the informal care system even in the midst of narrower base of formal care system. Noteworthy is that older people need care and support in order to undertake their activities of daily living (ADLs).

Old people are not well catered for in the country.

However, the survey data indicates that the extent of the inclusion of older adults in the Ghanaian society are clearly articulated along the trajectory of declining extended family support system, participation in policy issues, accessibility to FCPs as well as witchcraft accusations. These have been outlined in the sections that follow (figure 2).

Fig. 2 The Extent of Inclusiveness of Older Adults in Ghana (source: Field data).

Weakened Extended Family Support System and Social Inclusion

Social inclusion is shrinking, it is no longer what it used to previously. For example, the rendering of care is a dimension of social inclusion. This notion is suggestive of the fact that there is a reduction in the scale and/or extent of caregiving in contemporary society compared to the past. Doing so served as a node of social inclusion as well as functioning at the group level. Probably, this may have been caused by individualization, urbanization and modernization. Social inclusion in this context relates to an egalitarian society in which everyone is concerned about and care for others and their interests. The change in paradigm in the interview data is however due to the copying of western lifestyles by Ghanaians. Second, the fact that individuals in society have stopped doing things together as in the «fidodo regime» (i.e., peer support scheme) is a reflection of exclusion from participation in group level activities, albeit small. Kobla argues that the reduction in peer support is linked to the fact that the children of older adults have a low sense of duty and do not want to do anything for themselves and their parents. Below are the associated explanations. Kobla gives a different dimension to social inclusion as in peer support, which is reflected in the following activities — fetching water, fetching fuelwood, working on each other’s farms. On the basis of which members contribute to the work activities of each member. The quote below shows that engaging in the above indicated activities is indicative of care provision by the group members and therefore the larger society. He decried the fact that the node of inclusiveness described above is gradually eroding. Kobla’s quote stresses also the reverse case of inclusiveness. He also decried the failure of children to support their parents, rather they anticipate that all things will be done for them.

In the good old ages, everybody cared for and about everybody. Presently, the situation is not the same. Maybe inclusiveness is in a different dimension in recent times. In the village setting, peer support existed and somehow exists presently — in the form of fetching water, fetching fuelwood for each other, working on each other’s farms like the «fidodo» scheme. If there are five (5) people in number in a group, it will be done for all 5 individuals and it was fun at the time. This was long before we were born and we came to meet it. During our time, that inclusiveness has been eroding, until now everybody is on his own. But now even your own children want you to do everything for them.

Obenewaa and Lena share similar sentiments with Kobla, see quotes below. As noted by Obenewaa, this includes feeding of children. This is reminiscent of the neglect of the care needs of older people. Lena’s quote like that of Kobla emphasizes the significance of peer support and the fact that it has seized to function in contemporary times.

Even your own children will not help you because they think it is your duty to feed them (Nuworzamedo).

If my mum were sick, there was peer support but now that seems to have gone extinct (Lena).

Kobla and Morley further argued that:

if copying the west on issues related to what is child labour or not, it will be ideal for the state to adopt the old age home facility concept and system to reduce the effects of urbanization and modernity on older adults (Kobla).

Because if we are trying to copy, we have to copy well. Because in those old age homes, the old man himself is happy that he is going to make friends, he will talk to people every day instead of being alone and lonely… if they are 2, it is better since they keep each other company. Otherwise, dementia sets in because of the loneliness, perhaps depression as well, etc (Morley).

Morley observed that since Ghana adopts most welfare models, it should be able to adopt the residential care home model as an alternative to the extended family support system that is declining. This has the propensity to reduce dementia and depression among older people, which may be due to loneliness.

Similar to the indications of Kobla, Badu noted that the Ghanaian society was once a very socially inclusive society. However, that has changed due to the adaptation of western ways of doing things.

He opined that:

[…] the Ghanaian society was once an inclusive society until we started copying the west in everything.

In the above statement Kobla also recommended the institution of residential care homes for older people at state level.

Niko observed that it is as if Ghanaians know nothing and that it is the west that teaches them all things including the attributes of social inclusion. This point was made in the light of performing household chores such as sweeping, plate washing by children, which are now considered as child labor. This presupposes that there is the need to clearly delineate what constitutes household chores and those that constitute child labor. Falila concludes this point by saying that in this situation both parents and children have roles to play.

It is now that the west that is coming to teach us about social inclusion and all those kinds of things. If washing of plates and sweeping at home is child labor, when you grow how would you do it? (Niko).

If the youth are there performing their roles, their parents or older people will also be there to perform their duties (Falila).

In Ghana and therefore the society, there are people who act inclusively as far as the older people are concerned.

Social Inclusion through the Mode of Participation in Society

Normally, social inclusion finds expression in the attendance of community funeral activities and/or programs. Participation in social activities albeit private, public and/or family oriented is key in this context. It is noteworthy that participation may exist with older people not taking part, because they are not enthused about such activities that the opportunity of participation does not exist, let along accord individuals the choice to participate. In other cases, participation may exist but with slim chances for large numbers of people to be involved. The interview data show that different extents of social participation. For instance, Norman alludes to a little participation in society.

I am a house person. It is my disposition. I am always at home. I do not engage in social activities that often (Norman).

On the other hand, Adzoba and Nuworzamedo articulated they moderately participate in society activities that range from weddings to funerals.

I participate a lot in family related activities such as birthdays, weddings, funerals among others and that enables me to mingle with other people and cheer up a little. It is very necessary in order to snap out of the miseries of life (Adzoba).

Now the kind of participation we get ourselves involved in are funerals and things, that is the case. People participate in funerals more (Nuworzamedo).

Kobla also stated that he usually engaged community participation. He noted that:

I have observed severally that community participation is mostly at the community centers.

Morley argues that in the situation where social participation is absent, it means that there is no social inclusion at all or a reflection of social exclusivity.

It means some people are excluded. So, it is no longer social inclusion because the exclusivity is there (Morley).

When the required resources in society for example, fish stock are in short supply and/or inadequate such that some people get stranded with implications for the need to meet fundamental basic living conditions, social inclusion at this point is truncated, particularly when there is a reduction in the level of participation. The following observation pertains:

When you go to the fishing communities, where the fish stock is over fished or now they go and roam, roam and roam and come back with nothing and that is the work they do. Meanwhile, they have to eat and look after their children and so on and so forth. So, that is that social inclusion or protection increasing or diminishing? That is why the people involved in the thing should be increasing the things and also widening it (Badu).

Participation of older adults in healthcare is not there in the real sense of the word. Because society tends to forget about older people and their very existence once people attain 60 years and counting. In the words of Norman, participation in society can also be in the form of childcare support. Participation is affected by societal neglect of older people. This is further compounded by the segregation between older generation people and the younger ones due to the process of migration. This observation is explained by the fact that:

The thing is that when you are growing old then they forget about you. That is what it is currently in the society. You know, these days we migrate and things. So somewhere only older people are left behind or remain in the society. Thus, any place beyond Akosombo, it is now left with old people. They cannot get the thatch and sand when they are building their houses and that is how it remains until they die. When you go to the same places, you only see broken buildings. Yet, those places may have been vibrant cities 30-40 years ago. Prior to that if the youth are there, then the older ones will also do their jobs as the grandparents caring for their grandchildren (Norman).

From the point of view of burial of departed older persons and social inclusion, it can be observed that, there appears to be a shift in social inclusion in the view of Kobla and Morley. For instance, the care for another’s culture. This shows that some older people go through starvation and other unpleasant treatments but when they pass away, their funerals are massively attended. Yet, according to Kobla, when they were alive, they were not supported with the basic necessities of life such as food, love and care. But when they die almost everybody gets socially included in attending their funerals. Prior to their deaths, such older persons get excluded from the society in terms of the provision of basic needs of life. These have implications for care provision regarding the plight of older people. Thus, Kobla made the following observation:

In terms of inclusiveness, its only when the person is dead that they see everybody come around for their burial. Yet, before then, what to eat for such an elderly person is a problem (Kobla).

Morley documents that the burials of older people yield the attraction of funeral organisers namely undertakers, mourners, family members, friends and sympathizers alike. This may denote social inclusion on their part. However, it is at the exclusion of the departed older person.

The burial of departed older adults may yield the social inclusion of all and sundry, yet not the inclusion of the older person but the inclusion of funeral organizers namely undertakers, pastors, mourners, family relations, friends and sympathizers (Morley).

Formal Care Practices and Social Inclusion

Participating in or benefiting from social protection programs need not be based on age segregation. Rather, it should be without any form of barrier to ensure accessibility as a handle to availability even in the frame of state level formal support infrastructure (i.e., formal care practices), e.g., NHIS, LEAP, pension. These may tend to be restrictive. This is tantamount to age discrimination or ageist tendencies. Through the interview data, Kobla for instance perceived formal care practices from the viewpoint of people meeting his health needs. He is concerned that his pension income may not be adequate enough in meeting his health needs. He explained that:

Social protection is more for formal sector workers like me. At 65 years, I am supposed to enjoy the fruits of my labor that has been saved for and when I am 70 years, what I may get in pensions will not be adequate to cater for my health needs.

Badu notes in the quote below that the NHIS constituent of the FCPs is debilitated by drugs included under it and those not and the fact that older people have to bear the cost of the latter.

The NHIS itself has problems. Now you go to the hospital and they say this one is included and they are asked to go and buy it from the drugstore or pharmacy.

Falila is of the view that the LEAP program only covers a few older people. For this reason, it socially excludes some older persons. This can however be mitigated by including all older persons. Thereby making it socially inclusive for this category of people. in addition, Adzoba stated that older people have a myriad of problems including urinary incontinence, but who are excluded from the NHIS list of treatable conditions. this is an indication that older people have to pay for such medications themselves. She argues that medication should rather be free for older persons.

The LEAP program does not cover everybody. For politicians, when they pilot it with a few people, even three (3) people, they start making noise. It does not cover every elderly person. But the LEAP is there after piloting, why not extend to all others. So social exclusivity is here. Here, they can identify them and put difference in there for instance those who need the things so it becomes a whom you know kind of thing (Falila).

Older people have their own challenges when they are growing, e.g., problems with urination or urinary incontinence and all that but those things are excluded from the NHIS. It means that when you grow and reach the 70’s, you would pay for them. Its only paracetamol that they will give us. As we grow old, medication should rather be free for us. It must be made holistic (Adzoba).

In a similar vein, Kobla opined that medical care should be free for older people. further, easy access to social amenities such as water and electricity are key. In the absence of this, older people may have to travel far distances to access the same. People in Akatsi in the Volta region can only access clinics or hospitals in the big cities such as Adidome and Battor. Essentially, facts are all at odds with mandate of the formal care practices. In theoretical terms, the above findings are confirmed by the theoretical intimation of Riley et al. (1994) that the management of care principle is continually at odds with the realities of the various older populations in relation to healthcare needs and resources.

As older people grow older, they should make medical care free for them. Social amenities like water and electricity and others — there should be things that the society is trying to imitate what happens in the developed world but now we are not yet there. You can only access a clinic; the hospitals are in the big towns. So here at Akatsi, you can go to Adidome Hospital or Battor Hospital (Kobla).

Theoretically, the findings in this section reiterate Riley et al’s. (1994) articulation that state operationalization through policy and related program push out the responsible position of older people in terms of the quantity of services rendered to them through the mode of FCPs.

Transportation and Social Inclusion of Older People

Due to the commercial nature of the transportation system in Ghana, with a lesser percentage of public transport quota, the inclusion of older adults depends on patience and discipline of the drivers and mates involved when it comes to helping older adults. However, this is not a given because not all drivers/mates have these dispositions. For example: Lena notes with regard to mini buses (also known as trotro) in which older people are assisted in boarding. On the other hand, Kobla stressed the fact that in some cases, taxi drivers in display patience and discipline with older people in terms of supporting them to board taxis. Yet, this is not a given because not all taxi drivers do so.

Social inclusion in transportation systems, that one is commercial because the older person will be helped to enter the vehicle (Lena).

In the case of the taxis, the drivers help them to enter the vehicle. But it is not every taxi driver who has the patience and discipline, it depends on whom you meet (Kobla).

From the point of view of respect, the older adults mentioned that there is a change in terms of respect accorded them through the offering of their seats to them in the society. Badu argued that they used to revere the respect Ghanaians had for older people. But this does not reflect in the national policies for older persons. These facts are exemplified by the quotes of both Kobla and Badu as follows:

We are not given the respect due us. The youth don’t give their sits to older people anymore. Because of modernity, they think they have also paid their bus fares (Kobla).

Ghanaians in general have revered respect for older people but the same cannot be said in terms of national policies for the general welfare of older people (Badu).

The Burgeoning New Culture of Witchcraft Accusation and Social Inclusion of Older Adults

Pronouncements made by some pastors, label older persons as witches/wizards. Yet, such may not be a true reflection of the situation at hand. This fosters mistreatments towards older adults including their untimely deaths due mainly to the fact that accused older adults are the cause of the challenges or calamities that younger people may be experiencing. But this has dire implications for the building and sustenance of intergenerational relationships and/or solidarity. The theoretical implication of this lies in the statement by Goldstein, Miehls and Ringel (2009) that notes that there is the need to attune to plight of older people and elimination of countertransference attitudes that may interfere with empathy towards older people. Therefore, practically applying the notion attuning to the plight of older people and eliminating countertransference attitudes will generate more empathy towards older people the practical application of the phenomenon. Countertransference particularly that induced by the exclusive nature of FCPs and witchcraft accusations including other indignities of ageing such as urinary incontinence.

In some cases, such situations of atrocities may have been induced by medical health conditions such as dementia, which is characterized by forgetfulness, especially in affected older people admitting that they are witches/wizards whereas they are not. All older people cannot be witches/wizards by default or by virtue of age (i.e., old age). If this situation is allowed to fester on, a time will come when everybody in the Ghanaian society will be labelled as a witch/wizard particularly the females due to the feminization of witchcraft accusations, yet which will not be a true reflection of the situation on the ground. This makes witchcraft accusation a force of social exclusion, rather than a force of social inclusion. Hence, observations from Kobla show that some people are conscious in their dealings and treatment of older people including their children, whereas some are not. This is because they hear the pastor say that an older person is a witch. This implies that the older person is responsible for their calamities in life. as a result, they will do what it takes for him/her to die. He explained that:

Some people are mindful of older people especially their children. Some can be around but will not be mindful of the person’s age and so on. They may even be saying he/she is a witch and so on. Because the pastor has said it and so whatever they will do to him/her to die quickly is what they will do. Because the pastor has said it, it means that the state in which they are, it was the old man or woman who caused it. And so, they would have to mistreat him/her too.

As Nuworzamedo documents, such measures can be taken to the extreme including beheading the accused older people for bewitching them. He also observed that even the pastor may not be sure of his/her accusations of witchcraft. This presupposes that the entire witchcraft accusation thing is a «trial and error» phenomenon. Norman also said that apart of being beheaded accused older people of witchcraft are excommunicated from their resident towns. This is however not an indication of inclusiveness thing. The children of the accused connive and condone the act by virtue of participating in molesting accused older people.

There was a situation where they will go and cut off the head of the old man or woman with a cutlass when he/she will say the woman is a witch and therefore responsible for his troubles, that is why. But how do you know that the person is actually a witch or a wizard, pastors? It is really happening (Nuworzamedoo).

When older people are accused of being witches/wizards, there are places where they beat them and sack them from the town in which they live. Is that inclusiveness? And the person’s children are there ooo. But they will participate in the sacking. Or don’t those people have children? And they participate in the sacking of their parent(s), committing atrocities against older people (Norman).

It is worth noting that when cultural factor of witchcraft accusation becomes so entrenched in the society even beyond the current trends, it may lead to social disintegration with respect to older adults. Witchcraft accusation is a great determinant and facilitator of social exclusion of older adults. This has consequences for caregiving and planning in the country even at the individual, community and national levels. Relational social work seeks to enhance resilience and capacity to solve difficulties. Theoretically, this is a confirmation of Goldstein et al.’s (2009) argument that cultural factors have a bearing on the problems, personalities, motivation and strengths of older people. this calls for a major drastic change in the treatment of older persons. The above also confirms the structural lag theory of searching for potential solutions to situations with implications for the future (Riley et al., 1994). In place of which, there is the need for emphatic attunement to the plight of older people and as well eliminate attitudes of the countertransference nature which may interference with empathy towards older people (Goldstein et al., 2009).

Living Condition Challenges

In summary the problems that older people continue to encounter in their old age are varied. These encompass haphazardly implemented state policies; namely Ghana’s pension and system challenges; the shrinkage of the informal care system and narrower base of formal care system. The latter is due to the neglect of the care needs of older people; shrinkage of the significance of peer support and witchcraft accusation. In addition, there are some indignities associated with old age. The older adults also intimated that their dignity is at stake and needs to be re-visited and re-vamped. This issue actually has to do with the dignity of ageing as a process. These indignities have been expressed along the lines of old age-based diseases and/or conditions such as urinary incontinence, dementia and a host of others. It also emphasized the factor of intergeneration reciprocity. As part of the interview data, Obenewaa contends that indignities associated with ageing as far as dementia is concerned is the same as the dignity in terms of weighing situations. As Lena observed, another indignity associated with urinary incontinence. Adzoba noted for instance she was really concerned about an older person suffering from dementia and being robbed of his/her belongings as a result of that. Further, Niko also intimated that there is an indignity associated with dementia. These issues are clearly articulated in the following quotes:

The key thing for me is the dignity of ageing, and I don’t think anything stripes it away, dignity weighs as much as dementia does (Obenewaa).

[…] you can see the indignity when older person is unable to withhold urine (Lena).

And so, it’s not uncommon, isn’t uncommon to find or to hear of cases where the caregiver is seen as robbing the senior citizen, the person with dementia (Adzoba).

Dementia has a way of stripping away every shred of dignity, you know, so that even when the person is not aware, um they’ve gotten to the point where they barely know what’s going on around them, even the people around, can see the indignity, you know, and it’s not a pleasant thing, it’s not a pleasant thing at all, but that’s why we do what we do, so yeah (Niko).

As Kobla noted, one major of handling such issues is through closeness to health centers. Another way of salvaging the situation is for children to reciprocate the care they received from their parents.

But I think, um in my experience, proximity has made, has been a big determinant from where I sit, um, compared to other factors […] (Kobla).

Culturally, you’d say your mother took care of you when you were toothless, today she is toothless or today she’s struggling, how dare you turn your back on her (Falila).

Care Planning Framework: The Solution for Challenges

The interview data findings proffer the form social inclusion of older people should take in Ghana. The older people indicated that the social inclusion of older people in Ghana is very pertinent. Stated differently, the Ghanaian society can be made an old age friendly and therefore inclusive society when the following are taken into consideration.

- Decentralize social intervention programs and caregiver institutions like department of social welfare to the local assemblies and provide them with the needed logistics to operate.

- Provide decent accommodation for older adults and the needy in the society.

- Dedicate specific hospitals across the country which are disability friendly in terms of accessibility to solely attend to the heath needs of older persons and also register them on to an effective health insurance scheme.

- Provision of reliable and old age disability friendly vehicles or buses to facilitate their movement.

- Improve the current pension scheme to provide better monthly allowances to older people.

- Involve older adults in decision making especially on issues that concern them — e.g., in the formulation of social intervention policies.

- Improve, expand and increase the monthly allowance for pensioners and social protection program beneficiaries like LEAP.

- As part of its plan, the government should include older adults, the vulnerable, those with disabilities, the sick, to be taken care so that they will know that they are part of the country.

- Government should take advantage of technological dominance and create apps and programs to make movement for older people easy.

- A special day can be set aside in the calendar year to celebrate and honor them.

The older people studied were of the view that the above are their recommended ways of enhancing the reliance and capacities to solve challenges. Linking this is a key variable in relational application to social work. Noteworthy is that Ghana has two days for older adults that have been set aside and celebrated in a given year. The general one is that which is celebrated on October 1 each year, promulgated by the UN, that all countries abide by. The July 1 day one was instituted by the late President J.J. Rawlings, especially for Ghana. On this day, a cross section of older adults are usually selected and who dine with the president and they are also honored. However, when President Akufo Addo took over power, this has been changed. Peradventure, the re-institution of the latter may be pertinent.

The articulation of these social inclusion intervention-oriented measures is consistent with the structural lag theoretical stipulations of Riley et al. (1994) on potential solutions in the nearest future, a demand from the social institution, particularly the state.

Caring from the perspective of some older adults has to do with making available the requisite care resources for accessibility by older people. Therefore, based on the findings, this paper proposes a care plan framework which is constituted by a variety of recommendations for how to improve care for older people by expanding the frontiers of social inclusion of older adults in Ghana. This can be done from three main dimensions: first, expansion in the provision of FCP, second, a strategic nationwide establishment of old age home facilities; third, curtailment of witchcraft accusations against older adults. The quote by Badu displays divergent views on the issue. These are retirement planning in aid of life in old age, free healthcare and free food provision for older people.

The government should educate the public about life after retirement so that people can save enough to use when they retire. Also, the government should provide free healthcare and food for older people and make them feel special (Badu).

Niko also placed emphasis on full salaries for older persons in Ghana. he stated that:

It is because they don’t care about older people in the country as compared to some developed countries where older people get full salaries.

From the FCP dimension, Kobla recommended the provision of «residential home facilities» for older people at the state level, so that in the event of the neglect and abandonment of older people, they can be taken into these homes. Based on this, the care for older people involved will be provided by the state and therefore society. He observed that:

Then, they should provide homes for the elderly — older people’s homes to be at almost, if not every community, it should be at vantage places. So, when a person is old and the attention is no more forthcoming, they take the person there. In that case, society is taking care of older people. And I’m sure that will enhance inclusivity. In that case too, the whole society is taking responsibility for the older adults in the old age homes. Because the society, the government is providing the services or providing the services through an organization or organizations.

Adzoba adds to the discussion the fact that healthcare should be made free for older people. Hence:

To a greater extent, the social protection program namely LEAP, NHIS and pensions need to be nodes of social inclusion, not the other way round. First, to become more inclusive, the NHIS should not exclude certain medicines. The regulators should make everything exempt; older adults should not pay for them (Adzoba).

Interacting with people in the social context is ideal in the frame of residential home facilities and participation in them, if they are available, accessible and affordable according to Badu. Being in the company of others and interacting is also a mode of inclusivity and happiness among older people. However, sometimes the challenge is that some older adults ask unpleasant and irritable questions, such that need to be disregarded by the family members or hearers. He said that:

Older people sometimes ask weird questions and non-interesting questions that is part of the problem.

Kobla notes that the best way to boost inclusivity is for all hands-on deck by the state and faith-based organizations. He noted that:

There is the need to increase inclusivity of older persons with improved health facilities. Presently, health facilities exclude older people. That is what the government should do. Religious bodies and/or organizations can also do something to change the plight of older people but it is not mandatory. In the past, the religious bodies have done their best — to establish schools, hospitals/clinics but they cannot do it for free, else the facilities will collapse in the communities where they operate, so that they can get people to convert.

In summary, the care plan framework comprises measures such as expansion in the frontiers of formal support infrastructure for older adults, through policies dynamics e.g., passing into bill the national ageing policy, removing restrictions in the accessing existing FSI, eradication of witchcraft accusations and abolishment of witch camps nationwide and strengthening of families, particularly the connectors and plugs of reciprocity.

Discussion

The paper examined factors pertaining to how declining extended family support system, FCPs such as the NHIS and LEAP programs and witchcraft accusation shape the inclusion of older adults socially. These indeed are the factors that rather exclude older people from the society in Ghana. These in turn serve as barriers in one way or the other to social inclusion, which is influenced by diverse factors, namely religion (Wilde, 2018), policy, and limited resources (Dovie, 2020). The findings are contrary to the outcomes of other studies. For instance, in a study conducted by Blanchet, Gink, & Osei-Akoto (2012) on the effectiveness of the NHIS found that averagely individuals including older people enrolled on the insurance scheme are more likely to obtain prescriptions, visit clinics and seek formal healthcare when unwell.

Majority of the older people who took part in the study, have articulated that they do not feel included in the Ghanaian society. This presupposes that in their view, Ghana’s society is not exactly an inclusive one, especially for older people due to the non-participation of older adults in policy issues that concern them, participation in, and accessibility to FCPs with the many restrictions that they come with. This finding confirms the argument by Dovie (2020) of the near policy deficiency regarding older people in Ghana. Social exclusion from benefiting from policy provisions is an impending threat to the well-being of older persons. This is problematic because the increasing population of older people in Ghana requires the reverse, i.e., social inclusion as ageing is inevitable.

The process of improving the terms of participation in society for people who are disadvantaged on the basis of age, economic or other status through enhanced opportunities, access to resources, voice and respect for rights (Charity Commission, 2001) is imperative. In the content of this paper, Ghana will be said to have attained social cohesion when it fights exclusion (Charity Commission, 2001) through the measures proffered and many more.

The findings are reflective of the fact that rather than being nodes of social exclusion, the ideal situation needs to be that the state’s FCP programs namely LEAP, NHIS and pensions become nodes of extensive social inclusion, first and foremost from policy formulation and implementation perspectives, with implications for the enactment of the ageing bill because it will particularly delegate sectors, groups and individuals to be responsible in this regard. Similarly, the World Bank (2018) notes that social inclusion refers to the process where all individuals and groups in society are given the opportunity to engage in various social, economic and political systems. The World Bank records highlight the fact that the concept of social inclusion should not be merely seen as a process itself but as an outcome as well. This is because once inclusive policies are formulated and implemented in a particular society, the diversity of the people are valued, allowing all people to live happily in an engaging manner. It creates opportunities and abilities for all people and gives them respect to live in the society with dignity. From the findings, it can be observed that social inclusion is the opposite of social exclusion. It creates positive changes in a particular social setting so that practices and circumstances that create social exclusion can be eradicated. In other countries, various steps are being taken that would lead to social inclusion. One of the first steps is to eradicate poverty (Wilde, 2018) so that people can embrace the opportunities around them. It also aims to allow older people to actively participate in social settings and voice their opinions. It is believed that if these steps were carried out, they would enable older adults in particular to enjoy access to all services and opportunities.

Walsh, Scharf, & Keating (2017) including Walsh, Scharf, Van Regenmortel, & Wanka (2021) document that old-age exclusion involves interchanges between multi-level risk factors, processes and outcomes. Varying in form and degree across older adults’ life course, its complexity, impact and prevalence are amplified by old-age vulnerabilities, accumulated disadvantage for some groups, and constrained opportunities to ameliorate exclusion. Old-age exclusion leads to inequities in choice and control, resources and relationships, power and rights in key domains of neighborhood and community; services, amenities and mobility; material and financial resources; social relations; socio-cultural aspects of society; and civic participation. Old-age exclusion implicates states, societies, communities and individuals. Older persons are also predisposed to some indignities associated with ageing, albeit urinary incontinence, dementia. dementia has forgetfulness and maltreatments associated with it namely robbery of personal belongings associated with it by unscrupulous care providers.

Institution of a legal framework for handling issues of witchcraft accusation including the closure of witch camps across the country cannot be overemphasized. Because the stigmatization, stereotype and marginalization, vulnerabilities associated with the practice of witchcraft accusation, it is recommended that the state establishes state based old age homes, e.g., in the similitude of children’s homes, e.g., the Osu Children’s Home (Akpalu, 2007), which will serve as habitats for particularly neglected older adults with a surety for availability, accessibility and affordability. In addition to that, witch camps across the nation must be abolished. Further, this has become necessary considering the increasing ageing population of Ghana, in the midst of social exclusivity and weakening extended family support system. Witchcraft accusations against Ghanaian older adults and the atrocities associated to it are negative attitudes and discriminatory in nature (Azpitarte, 2013; Gooding et al., 2017).

Care planning for older persons is synonymous with social inclusion. In contemporary Ghana, the rules of social exclusion of older people find expression in the state’s social protection programs and/or formal care practices expressed in LEAP, NHIS, pensions appear to be bearers of older people’s inclusion and exclusion simultaneously in the Ghanaian society. Social inclusion is affected by witchcraft accusations with implications for social exclusion, stereotyping, marginalization, ostracization and isolation of older adults in the society. The latter point confirms observations of Brook and Jackson (2020). Therefore, the notion of witchcraft accusation is running counter to older people’s social inclusivity in the Ghanaian society. Collectively, these have implications for care planning at large, social exclusion, intergenerational solidarity, at the individual, community and national levels. In summary, the social inclusion of older adults from the viewpoint of the results herein presented is suggestive of expanding the frontiers of social inclusion at all levels in the Ghanaian society with policy implications in terms of the provision of free healthcare, free food, eradication of witchcraft accusations, increased pension income and a host of others.

The above care plan framework calls for innovative policy responses that will facilitate expansion in resources. The attainment of this is associated with social cohesion. According to the Charity Commission (2001), social cohesion can be attained and is necessary. It is used in social policy, sociology and political science to describe the bonds that brings people together in the context of cultural diversity.

The Dynamics of Social Participation and Social Inclusion