Childcare Deinstitutionalization in Armenia from the Systemic approach Perspective

Aino Alaverdyan

Researcher, Jyväskylä University of Applied Sciences, Finland; PhD student, University of Eastern Finland, Department of Health and Social Management, Finland; Adjunct Lecturer, American University of Armenia, Armenia.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Aino Alaverdyan

e-mail: aino.alaverdyan@jamk.fi

Abstract

This article sheds light on the system change that is taking place in the organization of childcare in Armenia from 2013 to 2021. The country is pivoting towards the modernization of the child protection system by deinstitutionalizing (DI) residential care into family-based alternative care and investing in community-based services and professional social work.

The history of orphans of the genocide and the paternalistic period of Soviet institutionalization have diminished its prominence at the systemic level.

The process of DI is comprehensive not only encompassing the closure or transformation of residential care and reunification of children with their families but affecting all components of the child protection system. Noteworthy, the DI reform in Armenia has resulted from active and professional work conducted by international organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as national NGOs.

Keywords

Deinstitutionalization, Childcare, Child protection system, Social work, Armenia.

Introduction

In the last decade, Central and Eastern European countries, including the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), have continuously been the frontrunners in the alarming statistics of high number of children in residential care (Moestue, 2011, p. 4).

The Eastern Europe and Central Asia have the second highest number of children in residential care, accounting at 204 per 100,000 children (UNICEF, 2023).

Institutionalization negatively impacts all aspects of children’s development (Konstantopoulou & Mantziou, 2020), especially in the development of young children (UNICEF, 2012).

According to the global systematic review, there were significant adverse effects of institutional care on children’s development concerning their physical growth, cognition, and attention, as well as weaker connections were identified with their socioemotional development and mental health (Van IJzendoorn et al., 2020).

Deinstitutionalization (DI) is a policy and process of transforming the child protection system to prioritize family-and community-based support, to prevent separation and reduce reliance on alternative care, especially residential (institutional) care for children and families in need (Davidson et al., 2017, p. 755; Forber-Pratt et al., 2020; Goldman et al., 2020).

The DI has been recently studied in other CIS countries, for example, Azerbaijan (Huseynli, 2018), Russia (Kulmala et al., 2020), Kazakhstan (An & Kulmala, 2021), Ukraine (Rosenthal et al., 2022), and Georgia, former CIS country (Ulybina, 2020). Despite the recent DI advancements in Armenia, there has been a lack of research conducted on its development.

Residential or institutional care is one of the non-family-based alternative care forms that can be organized by reception homes, short or long-term residential care, and group homes (UN General Assembly, 2009), or boarding schools (Petrowski et al., 2017, p. 391). Alternative care should only be used as a last resource and be seen as a temporary and short-term solution (UN General Assembly, 2009). The DI does not indicate that all temporary institutional care should be closed (Rákó, 2022, p. 289).

Fundamentally, the DI recognizes the human rights, dignity, and autonomy of an individual as key factors (An & Kulmala, 2021), and thereby, aligning with the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), and Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children.

The DI has gained recognition as a global social policy that has required over two decades of targeted policy work by different global actors, especially international organizations, such as the United Nations Children’s fund (UNICEF) (Goldman et al., 2020). Hence, it is on the current agenda of many other international and national non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (Ulybina, 2020, 2022).

In this research, the DI development is analyzed through the lenses of systemic approach offering a holistic view of the public sector and examining how different components interact within the system (Knapp, 1986; Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1992; Wulczyn et al., 2010).

This article examines how the development of childcare DI in Armenia (2013-2021) has aligned with the components of the child protection system based on key informant interviews and relevant documents. The article provides some insights into the DI progress of other CIS, as they share similar development with the Armenian reform.

Systemic approach to child protection

The CRC provides the legal basis for protection children from violence (Article 19), economic exploitation (Article 32), drug abuse (Article 33), sexual abuse (Article 34) and abduction (Article 35), and also providing special protection to children deprived of family environment (Article 20), during adoption (Article 21) and in refugee and asylum processes (Article 22) (United Nations, 1989). States are obliged to build child protection systems based on their available resources (Tobin & Cashmore, 2020). While the CRC guides the ratified countries, the design and implementation of child protection systems vary depending on the economic, social, political and cultural contexts and normative frameworks of countries (Wulczyn et al., 2010).

There is growing evidence that child protection system should be based on a systemic approach for helping to understand system interdependencies, identifying more effective solutions by examining the whole context and inform more sustainable reforms (Lane et al., 2016; Goldman et al., 2020; Munro, 2005). For addressing complex issues, like child’s repeat removals from a family, requires system thinking for deeper understanding of multiple interactions that have influence on the issue (Wise, 2021).

In the system thinking, human, e.g. social workers’, errors are the starting point for inquiry offering a complex view of causality that emphasizes understanding of these errors within context and evaluating whether high-quality work can be effectively conducted in that context (Munro, 2005). System approach in child protection can reduce inaccurate assessments and ineffective interventions thought improved organizational learning (Munro, 2010). According to Wulczyn et al. (2010), systems approach to child protection recognizes the interactive nature of its components that are:

- structures: formal and informal relationship between system components and actors, e.g. child, family, community, state;

- functions: governance, management and enforcement ensure basic operations of the system;

- capacities: human resources, infrastructure and funding in accordance with the system requirements;

- continuum of care: defining the system responses to rights violations by promotion, prevention and response;

- process of care: specifying the procedures of engaging children, families, and communities in identification, reporting, referral and investigation, assessment, treatment and follow-up;

- accountability: ensures child protection system goals are met by data collection, quality standards, research, analysis and communication on child rights.

All these aforementioned child protection system components are affected when childcare DI occurs, as changes in one part of the system affect other components (Wulczyn et al., 2010).

DI global policy framework and background in CIS

There is a robust international legal and guidance framework for the promotion of DI. Firstly, CRC obliges states to support families and legal guardians in their educational task by developing various services (article 18) and to organize alternative care for those children who are temporarily or long-term deprived of the right to live with their family, in order to protect their own interests (article 9, 20) (United Nations, 1989).

There are lack of support for families and legal guardians in CIS, as the majority of children that are living in residential care are social orphans who have either one or both parents alive with the main reason for institutional care being poverty-related (Ismayilova et al., 2023).

The CIS belongs to UNICEF’s Europe and Central Asia work area (ECA). ECA countries with the lowest gross domestic product (GDP), such as Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Armenia, also have the highest rate of poverty (30 percent) (UNICEF, 2017).

In Armenia, one out of three children are both poor and living in deprived conditions (Ferrone & Chzhen, 2016, p. 41). The lowest expenditures for social security among ECA countries are in Armenia (6.8 percent of GDP) and Kazakhstan (5.1 percent of GDP) (UNICEF, 2020, p. 3).

Since 2000, DI reforms have been implemented together with the investment and capacity support of international organizations such as UNICEF, EU, World Bank, and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) in Europe and Central Asia (Opening Doors for Europe’s Children, 2017; Ulybina, 2020; UNICEF, n.d.a). The DI is also stated as one of the priorities in the EU Strategy on the rights of the child (European Commission, 2021).

Social care services are mentioned to be as an agenda for increased priority for the World Bank, including the development of different care options for enhancing DI (World Bank Group, 2022, pp. 31-32). In 2018, Changing the Way We Care – USAID – funded initiative was established to concentrate solely on the advocacy of family-based-care and closure of residential care (Changing the Way We Care, n.d.).

The UNICEF has been actively leading DI reforms, particularly in being the main partner of governments in the reform and its coordination (Ulybina, 2020; Frimpong-Manso, 2014), developing national DI policies and strategies, monitoring their implementation (Huseynli, 2018) and collecting global and national data on children living in residential care (Cappa et al., 2022).

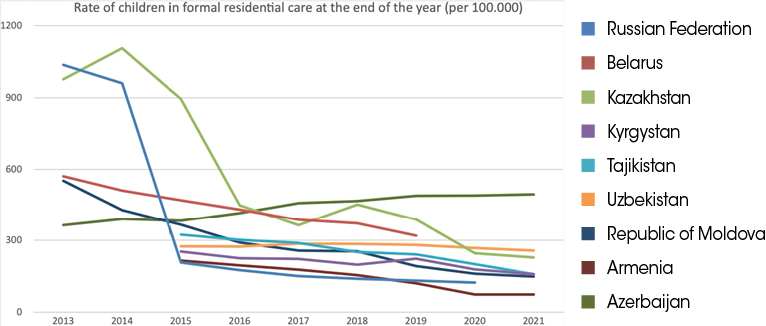

UNICEF aims to have zero children in institutional care by 2030 in the ECA region (UNICEF Regional Office for Europe and Central Asia, 2023, p. 43). This is a challenging task as the number of children in residential care is still high in the region, especially in CIS (Table 1).

|

Column1 |

Russian Federation |

Belarus |

Kazakhstan |

Kyrgystan |

Tajikistan |

Uzbekistan |

Republic of Moldova |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

|

2013 |

1037 |

571 |

977 |

552 |

364 |

||||

|

2014 |

960 |

511 |

1107 |

429 |

390 |

||||

|

2015 |

207 |

470 |

894 |

253 |

324 |

275 |

366 |

215 |

383 |

|

2016 |

175 |

431 |

449 |

225 |

302 |

274 |

291 |

195 |

416 |

|

2017 |

150 |

387 |

364 |

222 |

289 |

286 |

257 |

177 |

458 |

|

2018 |

139 |

372 |

452 |

198 |

251 |

285 |

254 |

154 |

467 |

|

2019 |

131 |

320 |

388 |

223 |

241 |

281 |

192 |

120 |

489 |

|

2020 |

123 |

246 |

178 |

200 |

269 |

160 |

73 |

490 |

|

|

2021 |

228 |

158 |

158 |

257 |

148 |

73 |

495 |

Table 1 Rate of children in formal residential care at the end of the year (per 100.000) in CIS, in the years 2013-2021 (UNICEF, n.d.-b)

The Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children strongly emphasize the prioritization of family care over institutional care for children under the age of three and condemn placements based on poverty (UN General Assembly, 2009).

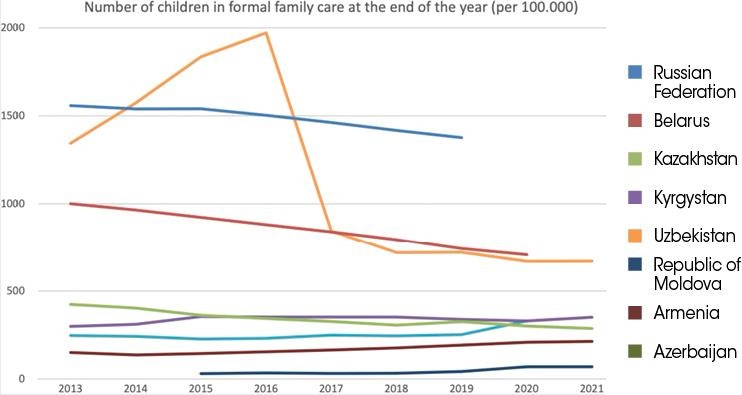

Foster care is one of the family-oriented solutions for alternative care, where children are placed by a competent authority in the domestic environment of a family other than the children’s own family that has been selected, qualified, approved and supervised for providing such care (UN General Assembly, 2009, p. 6). The foster care systems have been progressively increasing as an alternative care service in CIS (Table 2).

|

Column1 |

Russian Federation |

Belarus |

Kazakhstan |

Kyrgystan |

Uzbekistan |

Republic of Moldova |

Armenia |

Azerbaijan |

|

2013 |

1558 |

1001 |

424 |

299 |

247 |

1344 |

151 |

|

|

2014 |

1539 |

965 |

402 |

311 |

242 |

1573 |

137 |

|

|

2015 |

1540 |

923 |

362 |

355 |

227 |

1835 |

31 |

145 |

|

2016 |

1503 |

881 |

344 |

352 |

231 |

1971 |

35 |

155 |

|

2017 |

1462 |

840 |

327 |

352 |

249 |

845 |

32 |

165 |

|

2018 |

1417 |

795 |

306 |

352 |

245 |

719 |

33 |

177 |

|

2019 |

1376 |

742 |

326 |

339 |

252 |

721 |

43 |

193 |

|

2020 |

707 |

301 |

330 |

330 |

669 |

70 |

209 |

|

|

2021 |

287 |

351 |

670 |

70 |

214 |

Table 2 Number of children in family care at the end of the year (per 100.000) in CIS in 2013–2021 (UNICEF, n.d.-b)

A transition from residential care to family-based care is progressively taking place in Armenia, benefiting especially children aged 0-2 (UNICEF Regional Office for Europe and Central Asia, 2023, p. 40). In 2017, Moldova’s data experienced a significant drop, explaining that it now only accounts for family care, unlike before when it also encompassed children whose parents were abroad (UNICEF, n.d.-b). Another family-oriented form of alternative care is kinship placement, which involves a child’s extended family members or close family friends, either as official or informal caregivers (UN General Assembly, 2009). In official kinship placement, caregivers often receive financial support for the costs incurred in caring for the child (Petrowski et al., 2017). Relative placements and various guardian arrangements are common in Armenia and Russia (Center for Educational Research and Consulting & Save the Children, 2013; Biryukova & Makarentseva, 2021).

Secondly, CRPD obliges states to guarantee full human rights to children with disabilities and to organize special level of services and support to promote their social inclusion and independent life through a variety of services (United Nations, 2006). The number of children with disabilities in institutional care has remained relatively the same in the CIS due to the lack of support provided to the families and communities for reunifications and specialized foster care (Biryukova & Makarentseva, 2021, pp. 33-34; Jones et al., 2020, p. 7; UNICEF, n.d.-b).

Legacy of genocide and Soviet paternalistic culture in Armenian childcare

Armenia’s history of a genocide between 1915-1916 under rule of the Ottoman Empire (Morris & Zeʼevi, 2019, p. 486) led to many children becoming orphans and some of whom were placed in Ottoman state-run orphanages or organized foster placements (Grigoryan, 2022; Üngör, 2012, p. 176; Watenpaugh, 2013, p. 285). In 1921 there were 63,000 Armenian orphans in Ottoman orphanages (Üngör, 2012, p. 179); and approximately 100,000 were registered after the genocide (Kevorkian, 2021). Some of the orphanages were run by British, French, and American missionaries (Selva, 2019, p. 61), as well as single-women missioners from Scandinavia, who volunteered with Armenian orphans (Småberg, 2017; Okkenhaug, 2022). The collective memory of genocide orphans has deeply affected the emotional and cultural attitudes, especially diasporan Armenians, towards orphan care (Antonyan, 2017). This historical trauma continues to influence Armenian diaspora facilitating both formal and informal support for the childcare system in Armenia ranging from direct financial aid to families and running different services including orphanages, projects and programs, e.g. adoption related, in Armenia. There have been also advocacy efforts to transform the Armenian diasporan engagement towards community and family based services over residential care and orphanages (Barsoumian, 2012).

When coming to the Armenian Soviet period (1920-1991), the role of residential care was the most common form of alternative childcare as comparable to other Soviet nations (An & Kulmala, 2021; Ismayilova, Ssewamala & Huseynli, 2014). The childcare institutions were centralized services which allowed mothers to work for the collective economy and they provided a safety net for poor families (Popivanova, 2009, p. 984). The residential care in CIS followed the program of emotional socialization, which aimed to educate children and bring them up as ideal Communist citizens (Stryker, 2012). After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the role of residential care remained vital and it was still seen acceptable form of childcare (Carter, 2005, p. 8). Due to the legacy of genocide and Soviet paternalistic culture Armenian childcare system long time relied on residential care as the main and widely acceptable child protection service form. This article sheds light on the system change that is taking place in the organization of childcare in Armenia from 2013 to 2021 from tradition of residential care towards more holistic and systemic approach to child protection.

Research methodology

This research was qualitative containing key informant (n = 12) interviews and utilization of relevant documents for complementing the analysis of DI reform in Armenia between 2013 and 2021. Researching the DI topic over a period of eight years provided a comprehensive understanding of its development from the child protection system perspective regardless of changes in government. The application of child protection system model according to Wulczyn et al. (2010) provided a conceptual framework for understanding different key components of the child protection system and their interactions.

For conducting the thematic interviews, I was in direct contact with those professionals who were participating in the DI development work in Armenia. Ten of the interviewees worked in international or national organizations or NGOs as experts in education, child protection, social work, or rehabilitation. One of the interviewees worked as a consultant and one at the University. In 2013, seven face-to-face interviews were conducted; three of them participated in the research also in 2021. In 2021, five new professionals representing child protection NGOs participated in the research; two pair interviews were conducted online, and one gave written answers to the research questions.

The interviews were semi-structured with themes deriving from system theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1992; Wulczyn et al., 2010). Research information letters were sent to the interviewees before the interview and during the interview, a more detailed description was given. The interviewees gave their informed consent to participate in the study and its recording. Each interview lasted about an hour and was conducted without an interpreter, either face-to-face or via Teams.

I transcribed and coded the data of the interviewees (H 1-12) and classified indirect identifiers of the data, such as profession and nationality, to ensure anonymization. I utilized thematic analysis; the main themes and some sub-themes were formed deductively (Roberts et al., 2019, p. 2), originating from the system theory. I also searched openly for arising themes from the data, and defined and identified them as new sub-themes inductively (Nowell et al., 2017, p. 4). Some of the interviewees’ original expressions were maintained for highlighting sub-themes. In the 2021 interviews, results from 2013 were shared with the participants with targeted questions related to progress of the different components of the child protection system. In this process, no new themes were created, rather, they enriched the already existing analyses. The relevant documents, like UN Concluding Observations (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2013), were utilized as supporting materials for the results.

DI progress in Armenia (2013-2021)

Child protection system component of structures

Transformation of residential care reshapes both formal and informal relationship among system components and actors, including children, families, Armenian communities abroad and in-country, and state.

In 2015, the first children’s home (orphanage) was transformed into a child and family support center for disabled and disadvantaged children and their families, where 18-20 children had limited access to night care. Similarly, in 2016, one of the boarding schools was transformed into a similar center. After these pilot transformations, the DI proceeded to cover more children’s homes and boarding schools.

According to 2016, 2017 and 2018 Plan for Priority Issues and Measures of the Government, it was planned to «reorganize the institutions for social protection of the population within the system of the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (Vanadzor orphanage and five boarding schools for child care) into child and family support centers» (Armenia State party report, 2020, p. 12).

All in all, between 2017 and 2020, six boarding schools and one children’s home were transformed into new community-based services for children and families. «… As a result of these actions, the number of children living in institutional care has decreased: 12,700 children were in residential care in 2001, and in 2019 the number was 1,726…» (H8). The number of children in boarding schools has significantly decreased, as in 2020 there were 260 children and in 2013, there were about 700 children (Armenia State party report, 2020, p. 12).

In 2013, there were some cases reported of reunification of children from residential care with their families, but this practice was not deemed consistent. It was seen crucial that professionals should work with the families first-hand before reunifications and do prober assessment of support needs: «… that is why we think of involving in this process of reunification some kind of structures…» (H6). Within the research period, the process of care from the perspective of reunification practices became more consistent:

The measure aims to return children from childcare and protection institutions to biological families. Since 2014, 100 children have been involved in the measure carried out in above-mentioned marzes… 389 children will be returned to families and will be prevented from entering those institutions… (Armenia State party report, 2020).

Specifically, reunification processes with children with disabilities and their families were evaluated to be critical and challenging for the child protection system: «... Supporting, emotional and holistic support of a child when moving from one place to another requires a lot from the child, a lot from the family, also from the place where the child is being moved from...» (H1).

There is lack of official structures in the Armenian child protection system to address the following identified service needs of children and their families/caregivers. In Armenia the pivotal child protection service needs were identified among children with multiple disabilities living in rural areas as they are in high risk of abandonment to homes with no access to services. The lack of inter-sectoral data systems and reporting practices has an effect, especially on children with disabilities and their service provision, as the information sharing is problematic between different services, and families do not have the prober data about their child’s condition. According to the 2021 interviews, the provision of rehabilitation services at the local level was still incomplete, and the line ministries had not yet adopted a multidisciplinary rehabilitation approach. Thereby, many children with disabilities remain in residential care: «Because of difficult socio-economic conditions, the number of children with health problems in specialised orphanages has increased» (Armenia State party report, 2020, p. 14).

Another decisive social reason for child protection services was mentioned to be poverty experienced by families, causing various social difficulties for children such as malnutrition, dropping out of school, and lack of leisure activities. One interviewee reflected one client case: «I remember a single mother with three children, they asked us to place these children to boarding school for temporary basis...when I can afford their education and clothes, I will get back them… after few years, she took back the children from the boarding school…» (H7). Several families were mentioned to need after-school care and some families have pure housing problems, which have led to the placement of their children: «... mother… says that she has a problem nobody wants to rent her a house if they recognize that she has six children… so she needs these institutions for some of the children to rent an apartment…» (H2).

Based on the interviews in 2021, social housing solutions and independent living options were still mainly lacking. However, there were ongoing discussions with the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs (MoLSA) regarding the development of independent housing as part of the continuum of care for young people who are leaving residential care. One of the reasons mentioned for institutional placement was violent fathers or parental imprisonment. In 2021, the Karabakh conflict in 2020 and COVID-19 pandemic were highlighted as new risk factors for the wellbeing of children and their families, emphasizing the need for resilient child protection system. Especially, the war increased the number of single mothers headed families and disabilities among young men.

Child protection system component of functions

Armenian child protection system’s legal framework, enforcement, governance and management functions ensure operations of the system and child rights-based service delivery. Armenia ratified the CRC in 1993 (The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, n.d.). In 2005, Armenia ratified two additional protocols related to the participation of children in armed conflicts, as well as child trafficking and exploitation of children in prostitution and pornography, and in 2021 a third additional protocol was ratified regarding the right of appeal. The National Commission for Children’s Rights operates under the MoLSA as a consulting expert body in matters related to children’s rights. The Office of the Human Rights Defender has a separate department focusing on children’s rights, which monitors the implementation of CRC. Armenia joined the Council of Europe in 2001 and thus, its children’s programs and strategies also promote and monitor the implementation of CRC (Council of Europe, 2016). Additionally, in 2015, Armenia joined the Hague Adoption Convention, which protects adoption activities in the country (HCCH, n.d.).

In 2014, the Government of Armenia amended its national child protection strategy of 2013-2016 to meet the requirements of the UN Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children. According to the interviewees, various NGOs were involved in the planning of this strategy, and it was deemed comprehensive due to the successful advocacy campaigns of the international organizations and NGOs. The alternative care action plan approved in 2016 was also a great step forward in the DI (Armenia State party report, 2020, p. 4). The national child protection strategy of 2017-2021 was followed by a similar intersectoral planning involving many international organizations and NGOs as well as national NGOs in the process. According to interviewees, sufficient progress has been made in creating the necessary legal regulatory framework for the system to transition from residential care to family and community-based services.

The national level management and governance function of the three-tier child protection system has remained relatively consistent during the research period consisting of the management and governance of three different line ministries. MoLSA, as a leader of the DI reform, oversees the operations of residential care, daycares, and child and family support centers and is responsible for the accreditation and procurement of social services. MoLSA also coordinates the work with the national strategy and action plan, maintains the national databases of children in vulnerable situations and in adoptions, and trains social workers. Besides, MoLSA is responsible for granting all social security benefits. The Ministry of Regional Administration and Development (MoTA) supervises the activities of regional child protection units (CPUs) and local guardianship and trusteeship committees. In addition, MoTA is responsible for social workers. The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MoECSST) supervises the operations of boarding schools and regional pedagogic-psychological support centers, develops an inclusive education policy, and maintains a database of children in the education system.

The guardianship and trusteeship committees represent the local level management and governance function in Armenian child protection system. They continue to work voluntarily in various tasks, such as registering the birth of children, placing children into care, approving kindship care placements, and participating in the process related to the removal of parental rights. Due to the voluntary nature of the tasks, it is difficult to direct and supervise their work and to safeguard professional ethics in its various processes. These local committees operate in small communities, where people know each other well, so it is difficult for them to fulfill their duties, especially regarding the deprivation of parents’ rights: «... in many cases, they just don’t want to go to court, and even if they do, [they] have problems with the judges because only in really dangerous situations they take away parental rights...» (H9).

As international organizations and NGOs are key players in childcare DI in Armenia, the donor and program coordination and management function were one of the primary matters addressed in interviews. In the 2013 interviews, the weak public coordination and management of the different development programs was highlighted: «There is a lot of duplication of resources and funding, because each entity has its interests… because each organization reports to its donors...» (H3). The lack of donor coordination and management was considered to have a weakening effect on the impact of different programs, hindering the implementation of a sustainable child protection system. In 2021, the interviewees said that the government has taken the initiative to bring together different donors and map out various projects to support better coordination. In the meantime, for this coordination to be realized, international organizations and NGOs were acting as unofficial coordinating bodies in the dialogues between different donors and line ministries and thus, providing important leverage for the government. In 2021, it was mentioned that the cooperation between the different international and national NGOs have increased and so had the united discourse on the DI reform as it had progressed.

Child protection system component of capacities

The transition from residential care-based system to community-based requires new capacities among professionals but also among parents/caregivers. The interviewees mentioned that residential care workers need to change their attitudes towards the children living in residential care and their families, especially towards mothers: «... we can say that there is also stigmatization in the professional community, including those who are doing the DI reform…» (H10). In particular, the retraining of the employees of the institutions was seen important, which can best happen through on-the-job learning.

The NGOs have actively also trained teachers in child-friendly approaches, which has also contributed to the good progress of inclusive education in the country: «... so teachers must change their mentality so that inclusiveness applies to every child, and then they can adapt their teaching to children with special needs...» (H11).The interviewees recognized the need to educate the parents of children in residential care, which was not estimated to happen automatically without the NGOs’ involvement: «We used different cases and stories for them to help them to understand that they should be with their children and what are the consequences timewise if they leave their children at special institutions…» (H11). The interviews revealed that some poor families did not know about available family benefits and social assistance, even though their children were in residential care.

The international organizations and NGOs have been the key financiers and influencers of the child protection system’s human resources, infrastructure and funding in accordance with the new system requirements in Armenia. In 2013, it was expressed that the possible Eurasian Union (EAEU) membership would impede cooperation with the EU and hinder the progress of the DI reform. Although Armenia joined the EAEU in 2015, the opposite unfolded and a new EU partnership agreement was signed in 2017 (Eastern Partnership, n.d.).

The role of UNICEF was positioned to advocate the implementation of the CRC and support the government in DI coordination. The USAID has supported the DI implementation with technical assistance through UNICEF, World Vision, Save the Children, Bridge of Hope, and Fund for Armenian Relief, as well as EU has its’ own budget support programs. The World Bank has been actively involved especially in pre-school reform.

Interviewees stated that the DI process was initiated by UNICEF at the beginning of 2000 and since then, the Armenian government, in cooperation with international organizations and NGOS as well as with local NGOs, has implemented residential care reforms. The Child Protection Network is an important national NGO coalition for improving the DI in the country with its membership to the Black Sea regional child protection Child Pact network (ChildPact, n.d.). Moreover, the Armenian diaspora abroad was identified by interviewees as a strong economic and ideological support for the DI.

One of the core matters discussed was decentralization of child protection and family services and their funding. In 2013, the interviewees saw the need to decentralize funding and decision-making power to local governments: «... you have to look at both politics and funding in terms of reform...» (H5). The financing of social security programs is almost a third of the national budget expenditure, but most of it goes to pensions and various social benefits (Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, World Bank & UNICEF Armenia, 2020).

Different services are still poorly funded and social security is not targeted to citizens’ needs (Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, World Bank & UNICEF Armenia, 2020).

«I think it this process of DI requires more expenses; we have to create alternatives and finance parallel institutions and alternatives and then try to direct children from the institutions to alternative and then decline the funding of institutions» (H2).

In 2021, the government implemented the merger of smaller municipalities into larger municipal entities to make local administration more efficient in terms of decision-making and financial resources. In addition, in the spending framework between 2020-2022, the intersectionality of social security was considered for the first time, which in turn, was expected to promote multidisciplinary co-operation at national and local levels.

Child protection system component of continuum of care

While the DI process progressed in Armenia, the continuum of care of child protection system shifted towards more preventive community- and family-based services and foster care development took its place in the system as an alternative care form (response). The introduction of a gatekeeping funding mechanism of residential care services was seen as a critical move towards DI for creating an enabling environment for development of the continuum of care. In 2013, the funding system for residential care was contemplated to favor large institutions and wasn’t considered open: «... funding goes to institutions on a child-by-child basis, which makes the matter even worse, and institutions are interested in attracting more children to institutions... child-hunting occurs... managers invite to visit institutions...» (H6). In 2021, the process of care had developed in such a way that parents can only decide to place their children in residential care with an official letter to the regional CPUs.

A contrasting narrative was also reported in 2013, as due to the DI policies of not allowing even temporary institutional care, families in difficult circumstances were not provided with any support. This was assessed as negatively impacting those children in acute need. For responding to this need, new forms of temporary child protection crisis centers were established, where children can stay for a maximum of six months during the professional assessment period.

In 2021, many NGOs shifted their focus towards preventive services for children and families, such as providing psychosocial or humanitarian assistance, rather than solely focusing on the response services. A key development in the continuum of care, particularly in the response phase, was the adoption of family or foster care as a suitable alternative care solution which was discussed in 2013 interviews and later approved by the government as official service models.

The Concluding Observations of the Committee on the Rights of the Child (2013, p. 7) also placed pressure for development of family-based care: «Alternative family-based care and community-based care systems for children deprived of family environment are insufficient». In 2019, approximately 412 children were placed in alternative care facilities, out of which 57 children were placed in foster care. Over the years, the number of foster families has grown to about 90 foster families. The interviewees brought up the current need to train foster families for children with disabilities and behavioral disorders.

On the other hand, placement based on kinship was seen as a good informal structural alternative to formal foster care in a culture where family ties are naturally strong. Kinship placements were considered an informal form of family placement. Interviewees had contradictory opinions about kindship arrangements proposing them to be more supported or leaving them voluntarily as they are.

Child protection system component of process of care

The development of social work profession and functions within the child protection system institutionalized the process of care related to professional social work processes of identification, reporting, referral, investigation, assessment, treatment and follow-up.

Since 2010, UNICEF promoted the model of Integrated Social Services (ISS) at the regional level by shifting the focus from standardized social services to needs-based support provided by capacitated case managers (CMs) and bringing different social service providers under one roof (Arakelyan & Antonyan, 2014; Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, World Bank & UNICEF Armenia, 2020, p. 12). In 2013, the ISS was not yet seen as a comprehensive solution, as CMs were considered to need different services to support them in making actionable client plans for children and families. Additionally, the division of tasks between community social workers and CMs working at the regional level was still unclear. In 2021, the distribution of the different roles of social workers had become clearer, although there were still overlaps of different job descriptions in practical work.

In 2021, the government, in cooperation with the NGOs, was also planning the reform of the regional social offices (ISS centres), with the goal of connecting CMs more with community social workers and local social services improving the process of care, especially related to identification of social needs, their assessment, referral, treatment and follow-up.

In 2021, together with municipal reform, the government was introducing the policy that every municipality with 5,000 inhabitants should have a community social worker (Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, World Bank & UNICEF Armenia, 2020, pp. 12, 63). The National Association of Social Workers was evaluated to play an important role in advancing the social work profession in Armenia.

Child protection system component of accountability

An important phase of DI affecting the longer-term system accountability, was the conceptual consensus-building discussions on alternative care among key child protection actors in Armenia.

In 2013, the interviewees emphasized the importance of creating alternative care before starting the reduction of residential care and taking time for the DI learning process itself: «... we learn by doing, but also by not doing...» (H5).

In general, defining the concept of alternative care and services felt to be important, as there was also a fear that «orphanages» would be turned into new institutions. This evolving understanding of alternative care was adopted in 2019 by the government, clearly highlighting the fact that the primary alternative form of care is family-based solutions.

«… all the problems are coming that in the field level we don’t have service provision…when the communities, cultural understanding, will discover that there are solutions created like family-based, family-related, all the things will find their places very quickly…» (H3).

In 2021, interviewees confirmed that these wishes for accountability driven alternative care services were considered in the design of the DI process and time was set aside for creating a shared understanding about the services suitable for the country’s context.

The creation of new quality care standards was a significant step for accountability of the child protection system to meet its’ new set goals aligned with DI. Although the public body implements statutory quality monitoring and inspections of services, monitoring also appeared to be the work of the NGOs.

Under MoLSA, there is a monitoring group for residential care institutions consisting of several NGOs, whose report in 2014 initiated the reform by revealing that many of the children in residential care were there without proper reasons. In 2021, the NGOs’ attention was already more focused on developing the quality standards and monitoring framework for community-based services rather than revealing the violations in residential care.

The role of media in promoting DI reform was not yet seen as very active in 2013, especially at the local level. In 2021, the NGO representatives said that they have organized several discussions with the media, which have had positive effects on the media’s attitude towards the DI and on sharing information about it.

The interviewees estimated that societal awareness of the negative effects of institutional care for children is still low in rural areas: «International examples show that resistance from local communities is often one of the most important obstacles to the implementation of successful DI» (H8).

In addition, the NGOs have conducted communication campaigns to Armenian diaspora for supporting family-based services instead of institutional care.

Conclusions

This article sheds light to systemic change that is taking place in the organization of childcare during 2013-2021 in Armenia. In conclusion, the country is turning into the modernization of the child protection system by transforming residential care into family- based alternative care and investing in community-based services and professional social work. The relatively small population size of Armenia, approximately 2.78 million, did not simplify or fasten the DI process as it might be assumed. Resulting from the emotional history of genocide orphans and paternalistic period of Soviet institutionalization, the DI process has taken time to evolve in Armenia. Considering these findings, they have diminished their prominence at the child protection system. In other words, the social change is emerging among the actors of the Armenian child protection system, especially among service providers, professionals, but also among community members and diasporan Armenians, regarding the shared understanding of the child’s advantage to living in a family environment and seeing alternative, especially residential, care as the last option.

All the development considered, the DI reform in Armenia has been the result of active and professional work conducted by international organizations and NGOs as well as national NGOs during a span of 20 years. The results are consistent with previous findings about the roles of international and national NGOs in DI process: advocating and raising awareness (Opening Doors for Europe’s Children, 2017), educating families about their rights (Laklija et al., 2020), developing case management systems (Goldman et al., 2020), providing services, drawing policies and legislation (Bindman et al., 2019), working with quality standards of care and monitoring children in alternative care (Ivanova & Bogdanov, 2013). The DI case of Armenia is supporting the findings of Ulybina (2022), that although the strong pressure and guidance by international organizations and NGOs for DI reform, the national actors took the prober time to build up the consensus on the suitable services and practices for the country context. The international organizations and NGOs were often the providers, but the agency of national actors was strong (Heinrich, 2021) in the DI development in Armenia.

This study offers a contribution to the ongoing discussion on a systemic approach to child protection (Lane et al., 2016; Goldman et al., 2020), by utilizing the approach in the analysis of the DI process. Results on Armenian DI process validate that all components of the child protection system (Wulczyn et al., 2010): a) structures, b) functions, c) capacities, d) continuum or care, e) process of care and f) accountability, are affected in the process of DI.

(a) Armenia represents a less formally structured system, where informal relationships between system components exists. This implies that families, relatives, and community members including Armenian diaspora, also have active responsibility for implementing childcare and child protection services (Wulczyn et al., 2010, p. 23). Local guardianship and trusteeship committees are good examples of this extended role of the community, as they work voluntarily to carry out important official management and enforcement functions. This increases vulnerabilities of the operations of other system parts, if the local level of the system is not functioning professionally or effectively.

(b, c) The functions and capacities of child protection system have been developed during the research period in accordance with the new system requirements comprehending national and local level management and governance functions, donor and program coordination and management functions as well as decentralization of services and funding. The government-led intersectoral planning process of national child protection strategy has been an important forum for international organizations and NGOs, as well as national NGOs to participate in the policy planning and collaborate for the common goal of DI. The NGOs have also been active in piloting new service models with different public funding sources.

(d) The continuum of care in Armenia, is now perceived not only as responding to the acute needs of childcare by providing residential care but more as a provision of professional social work and preventive community-based services, prioritizing family-based alternative care options in response and promoting the holistic well-being of children and families. One task to be addressed in further development of the continuum of care is the formalization of various kinship and guardian arrangements as part of foster care.

(e) The great advancement related to the process of care was the introduction of the gatekeeper mechanism at the regional CPUs preventing easy residential care placements. For consolidating the process of care, it is certainly also needed to develop standardized practices of referrals, need assessments, and customer plans across different child protection services.

(f) There is still work to do on the accountability of the child protection system as transparent and digital data collection and reporting practices of different services are under development. There is a need for more specified data collection on children in alternative care for supporting the evidence based policy planning and for further enhancing the DI reform (Cappa et al., 2022). Besides, the continuing work in research, for example on the outcomes for children who are and who have been in alternative care, is vital (UNICEF Europe and Central Asia Regional Office, 2021, p. 80). The awareness of citizens of the DI reform, their rights, and available support with the means of effective communication is also one key area of improvement in respect to accountability. The monitoring of quality standards of childcare can no longer rest solely on the NGOs as in their new roles as public service providers they have a biased position as monitors for placing the accountability of the system at risk.

The future research is needed on Armenian childcare DI and its progress, especially considering the situation of children with disabilities. The situation with children with disabilities continued to be a common concern, as there was still a lack of specialized services. For better meeting these needs, the intersectoral structures and capacities produced by the child protection system are critical development areas (Jones & Gallus, 2016). From the structural perspective, it is important to enhance the partnerships and cooperation with other systems such as social security, education, and healthcare for enabling multidisciplinary approaches in service provision to meet the diverse needs of children with disabilities and their families/caregivers. In many cases, it comes to a need to clarify and extend the role of social work in these new child protection environments.

References

An, S., & Kulmala, M. (2021). Global deinstitutionalisation policy in the post-Soviet space: A comparison of child-welfare reforms in Russia and Kazakhstan. Global Social Policy, 21(1), 51-74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468018120913312

Antonyan, M. (2017). Social heritage of orphan care. Main Issues of Pedagogy and Psychology, 13(1), 56-68. https://doi.org/10.24234/miopap.v13i1.226

Arakelyan, H., & Antonyan, M. (2014). Integrated social services in Armenia: Improving social welfare for Armenian families and children. Global Social Services Workforce Alliance. https://socialserviceworkforce.org/resources/integrated-social-services-in-armenia-improving-social-welfare-for-armenian-families-and-children/

Armenia State party report. (2020). Combined fifth and sixth periodic reports submitted by Armenia under article 44 of the Convention, due in 2019. Committee on the Rights of the Child.

Barsoumian, N. (2012). Ending the era of orphanages in Armenia. The Armenian Weekly. https://armenianweekly.com/2012/08/15/ending-the-era-of-orphanages-in-armenia/

Bindman, E., Kulmala, M., & Bogdanova, E. (2019). NGOs and the policy-making process in Russia: The case of child welfare reform. Governance, 32(2), 207-222. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12366

Biryukova, S., & Makarentseva, A. (2021). Statistics on the deinstitutionalisation of child welfare in Russia. In M. Kulmala, M. Jäppinen, A. Tarasenko, & A. Pivovarova (Eds.), Reforming child welfare in the post-Soviet space: Institutional change in Russia (pp. 23-46). Routledge.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development. Experiments by nature and design. Harward University Press.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992). Ecological Systems Theory. In U. Brongenbrenner (Ed.), Making Human Beings Human. Bioecologixal Perspecives on Human Development. (pp. 106-173). SAGE.

Cappa, C., Petrowski, N., Deliege, A., & Khan, M. R. (2022). Monitoring the situation of children living in residential care: Data gaps and innovations. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 17(2), 110-118. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2021.1996669

Carter, R. (2005). Family matters: A study of institutional childcare in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. EveryChild. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/8f7ee9a/

Center for Educational Research and Consulting, & Save the Children. (2013). Development perspectives of foster care in Armenia: Research analysis results. Save the Children. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/a491638/

Changing the Way We Care. (n.d.). About us. https://www.changingthewaywecare.org/about-us/

ChildPact. (n.d.). ChildPact. https://childpact.org/about-us/about-2/

Committee on the Rights of the Child. (2013). Concluding observations: Armenia. https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/crc/docs/co/CRC-C-ARM-CO-3-4.pdf

Council of Europe. (2016). Council of Europe strategy for the rights of the child 2016-2021. https://search.coe.int/cm/Pages/result_details.aspx?ObjectID=09000016805c1d08

Davidson, J. C., Milligan, I., Quinn, N., Cantwell, N., & Elsley, S. (2017). Developing family-based care: Complexities in implementing the UN Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children. European Journal of Social Work, 20(5), 754-769. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2016.1255591

Eastern Partnership. (n.d.). Facts and figures about EU-Armenia relations. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eap_factsheet_armenia_eng_web.pdf

European Commission. (2021). EU strategy on the rights of the child. Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2838/713737

Ferrone, L., & Chzhen, Y. (2016). Child poverty in Armenia: National multiple overlapping deprivation analysis. UNICEF Office of Research.

Forber-Pratt, I., Li, Q., Wang, Z., & Belciug, C. (2020). A review of the literature on deinstitutionalisation and child protection reform in South Asia. Institutionalised Children Explorations and Beyond, 7(2), 215-228. https://doi.org/10.1177/2349300320931603

Frimpong-Manso, K. (2014). From walls to homes: Child care reform and deinstitutionalisation in Ghana. International Journal of Social Welfare, 23(4), 402-409. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12073

Goldman, P. S., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Bradford, B., Christopoulos, A., Lim Ah Ken, P., Cuthbert, C., Duchinsky, R., et al. (2020). Institutionalisation and deinstitutionalisation of children 2: Policy and practice recommendations for global, national, and local actors. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(8), 606-633. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30060-2

Grigoryan, H. (2022). Food procurement methods during the Armenian Genocide as expressions of «unarmed resistance»: Children’s experiences. International Journal of Armenian Genocide Studies, 6(2), 40-52. https://doi.org/10.51442/ijags.0022

HCCH. (n.d.). HCCH members. https://www.hcch.net/en/states/hcch-members/details1/?sid=81

Heinrich, A. (2021). The advice they give: Knowledge transfer of international organisations in countries of the former Soviet Union. Global Social Policy, 21(1), 9-33.

Huseynli, A. (2018). Implementation of deinstitutionalization of child care institutions in post-Soviet countries: The case of Azerbaijan. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 160-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.10.020

Ismayilova, L., Claypool, E., & Heidorn, E. (2023). Trauma of separation: The social and emotional impact of institutionalization on children in a post-Soviet country. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 366. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15275-w

Ismayilova, L., Ssewamala, F., & Huseynli, A. (2014). Reforming child institutional care in the post-Soviet bloc: The potential role of family-based empowerment strategies. Children and Youth Services Review, 47, 136-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.09.007

Ivanova, V., & Bogdanov, G. (2013). The deinstitutionalization of children in Bulgaria: The role of the EU. Social Policy & Administration, 47(2), 199-217. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12015

Jones, J. L., & Gallus, K. L. (2016). Understanding deinstitutionalization: What families value and desire in the transition to community living. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 41(2), 116-131.

Jones, M., DeRuyter, F., & Morris, J. (2020). The digital health revolution and people with disabilities: Perspective from the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 381. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020381

Kevorkian, R. (2021). From a monastery to a neighbourhood: Orphans and Armenian refugees in the Armenian Quarter of Jerusalem (1916-1926), reflections towards an Armenian museum in Jerusalem. Contemporary Levant, 6(2), 141-157. https://doi.org/10.1080/20581831.2021.1898124

Knapp, M. (1986). The economics of social care. Macmillan.

Konstantopoulou, F., & Mantziou, I. (2020). Maltreatment in residential child protection care: A review of literature. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience & Mental Health, 3(2), 99-108. https://doi.org/10.26386/obrela.v3i2.171

Kulmala, M., Jäppinen, M., Tarasenko, A., & Pivovarova, A. (2020). Introduction: Russian child welfare reform and institutional change. In M. Kulmala, M. Jäppinen, A. Tarasenko, & A. Pivovarova (Eds.), Reforming child welfare in the post-Soviet space: Institutional change in Russia (pp. 3-19). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003024316

Laklija, M., Milić Babić, M., & Cheatham, L. P. (2020). Institutionalization of children with disabilities in Croatia: Social workers’ perspectives. Child & Youth Services, 41(2), 184-203. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2020.1752170

Lane, D. C., Munro, E., & Husemann, E. (2016). Blending systems thinking approaches for organisational analysis: Reviewing child protection in England. European Journal of Operational Research, 251(2), 613-623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2015.10.041

Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, World Bank, & UNICEF Armenia. (2020). Core diagnostic of the social protection system in Armenia. https://www.unicef.org/armenia/en/reports/core-diagnostic-social-protection-system-armenia

Moestue, H. (2011). At home or in a home? Formal care and adoption of children in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. UNICEF Regional Office for Central and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CEE/CIS). https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/12de1d8/

Morris, B., & Zeʼevi, D. (2019). The thirty-year genocide: Turkey’s destruction of its Christian minorities, 1894-1924. Harvard University Press.

Munro, E. (2005). Improving practice: Child protection as a systems problem. Children and Youth Services Review, 27(4), 375-391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.11.006

Munro, E. (2010). Learning to reduce risk in child protection. British Journal of Social Work, 40(4), 1135-1151. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq024

Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1609406917733847. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

Okkenhaug, I. M. (2022). A Danish corner in the heart of Lebanon: Protestant missions, humanitarianism, and Armenian orphans, ca. 1920-1960. Mélanges de l’École Française de Rome. Italie et Méditerranée, 134(2), 251-266. https://doi.org/10.4000/mefrim.12487

Opening Doors for Europe’s Children. (2017). Deinstitutionalisation of Europe’s children: Questions and answers, campaign material. https://www.eurochild.org/uploads/2021/02/Opening-Doors-QA.pdf

Petrowski, N., Cappa, C., & Gross, P. (2017). Estimating the number of children in formal alternative care: Challenges and results. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 388-398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.026

Popivanova, C. I. (2009). Changing paradigms in child institutionalization: The case of Bulgaria. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(10), 984-986. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b395aa

Rákó, E. (2022). Deinstitutionalisation in Hungarian child protection: Policy and practice changes in historical contexts. Journal of Childhood, Education & Society, 3(3), 275-292. https://doi.org/10.37291/2717638X.202233191

Roberts, K., Dowell, A., & Nie, J.-B. (2019). Attempting rigour and replicability in thematic analysis of qualitative research data: A case study of codebook development. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0707-y

Rosenthal, E., Kurylo, H., Milovanovic, D. C., Ahern, L., & Rodriguez, P. (2022). Human rights bulletin: Protection and safety of children with disabilities in the residential institutions of war-torn Ukraine: The UN guidelines on deinstitutionalization and the role of international donors. International Journal of Disability and Social Justice, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.13169/intljofdissocjus.2.2.0015

Selva, S. (2019). Through the lens of childhood: An alternative examination of the Armenian genocide. Aisthesis, 10(1), 57-64.

Småberg, M. (2017). Mission and cosmopolitan mothering. Social Sciences and Missions, 30(1-2), 44-73. https://doi.org/10.1163/18748945-03001007

Stryker, R. (2012). Emotion socialization and attachment in Russian children’s homes. Global Studies of Childhood, 2(2), 85-96. https://doi.org/10.2304/gsch.2012.2.2.85

The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. (n.d.). UN treaty body database: Reporting status for Armenia. https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/TreatyBodyExternal/Countries.aspx?CountryCode=ARM&Lang=EN

Tobin, J., & Cashmore, J. (2020). Thirty years of the CRC: Child protection progress, challenges and opportunities. Child Abuse & Neglect, 110, 104436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104436

Ulybina, O. (2020). Transnational agency and domestic policies: The case of childcare deinstitutionalization in Georgia. Global Social Policy, 20(3), 333-351. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468018120926888

Ulybina, O. (2022). Explaining the cross-national pattern of policy shift toward childcare deinstitutionalization. International Journal of Sociology, 52(2), 128-155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2022.2031488

UN General Assembly. (2009). Guidelines for the alternative care of children. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/673583

Üngör, U. Ü. (2012). Orphans, converts, and prostitutes: Social consequences of war and persecution in the Ottoman Empire, 1914-1923. War in History, 19(2), 173-192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0968344511430579

UNICEF. (2012). Children under the age of three in formal care in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: A rights-based regional situation analysis. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/5e4852c/

UNICEF. (2017). Child poverty in Europe and Central Asia Region: Definitions, measurement, trends and recommendations. https://www.unicef.org/eca/media/3396/file/Child-poverty-regional-report.pdf

UNICEF. (2020). Realising children’s rights through social policy in Europe and Central Asia: A compendium of UNICEF’s contributions (2014-2020). https://www.unicef.org/eca/reports/realising-childrens-rights-through-social-policy-europe-and-central-asia

UNICEF. (2023). Children in alternative care. UNICEF Data: Monitoring the Situation of Children and Women. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/children-alternative-care/

UNICEF. (n.d.-a). 15 years of de-institutionalization reforms in Europe and Central Asia: Key results achieved for children and remaining challenges. https://www.unicef.org/eca/sites/unicef.org.eca/files/2018-11/Key%20Results%20in%20Deinstitutionalization%20in%20Eeurope%20and%20Central%20Asia_0.pdf

UNICEF. (n.d.-b). TransMonEE dashboard. https://www.transmonee.org/dashboard?prj=tm&page=child-protection#cpc

UNICEF Europe and Central Asia Regional Office. (2021). Better data for better child protection systems in Europe: Mapping how data on children in alternative care are collected, analysed and published across 28 European countries. https://eurochild.org/uploads/2022/02/UNICEF-DataCare-Technical-Report-Final.pdf

UNICEF Regional Office for Europe and Central Asia. (2023). Situation analysis of children rights in Europe and Central Asia. https://www.unicef.org/eca/media/27346/file/Report.pdf

United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities

Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Duschinsky, R., Fox, N. A., Goldman, P. S., Gunnar, M. R., Johnson, D. E., et al. (2020). Institutionalisation and deinstitutionalisation of children 1: A systematic and integrative review of evidence regarding effects on development. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(8), 703-720. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30399-2

Watenpaugh, K. D. (2013). Are there any children for sale? Genocide and the transfer of Armenian children (1915-1922). Journal of Human Rights, 12(3), 283-295. https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2013.812410

Wise, S. (2021). A systems model of repeat court-ordered removals: Responding to child protection challenges using a systems approach. The British Journal of Social Work, 51(6), 2038-2060. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaa031

World Bank Group. (2022). Charting a course towards universal social protection: Resilience, equity, and opportunity for all. https://hdl.handle.net/10986/38031

Wulczyn, F., Daro, D., Fluke, J., Feldman, S., Glodek, C., & Lifanda, K. (2010). Adapting a systems approach to child protection: Key concepts and considerations. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265279836_Adapting_a_Systems_Approach_to_Child_Protection_Key_Concepts_and_Considerations

Alaverdyan, A. (2025). Childcare Deinstitutionalization in Armenia from the Systemic approach Perspective. Relational Social Work, 9(1), 110-131, doi: 10.14605/RSW912506.

Relational Social Work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License